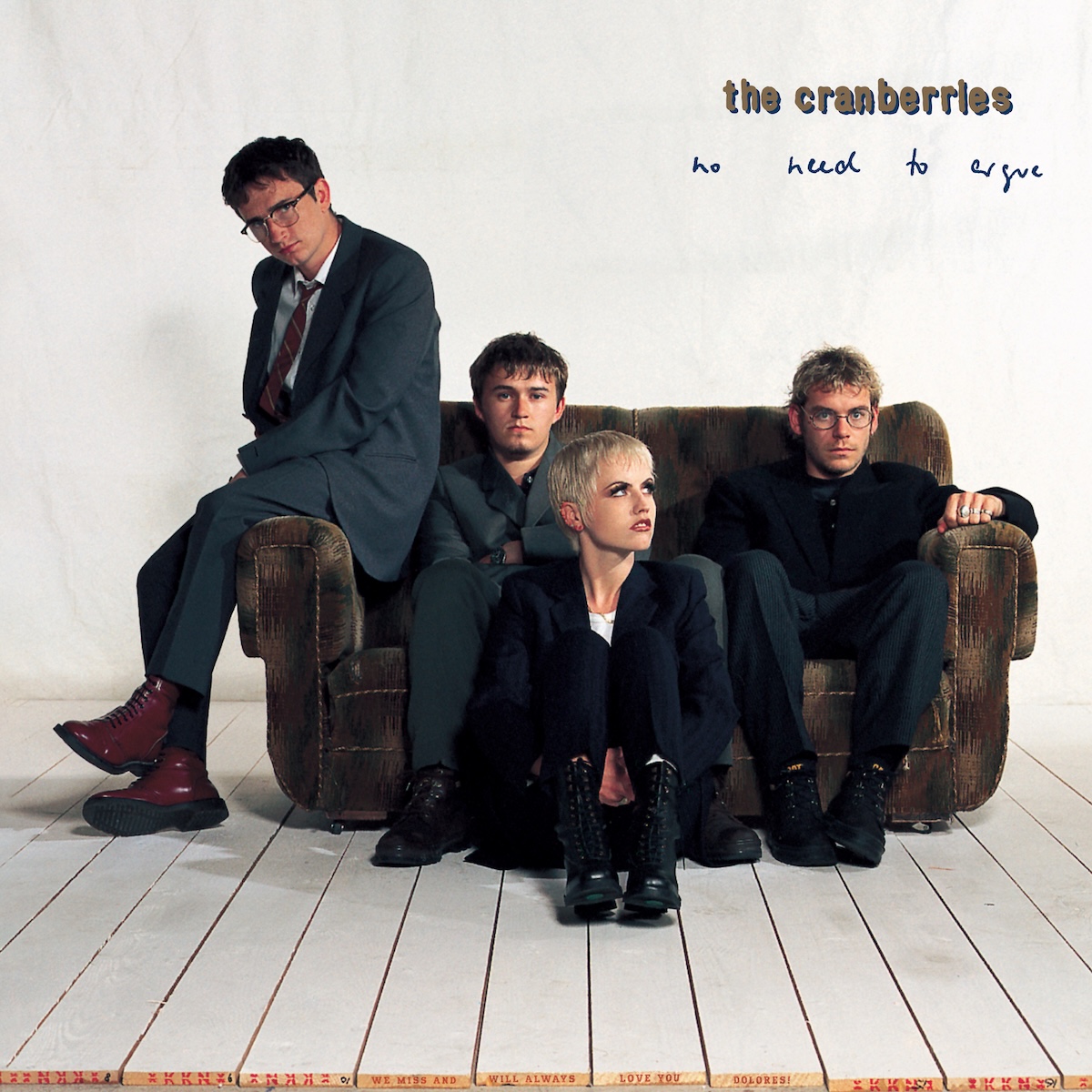

Thirty years after its release, the second album from Irish alternative rockers the Cranberries has lost none of its power. Fronted by the compelling presence of vocalist Dolores O’Riordan, the Cranberries built upon the success of their 1993 debut with the sophomore slump–defying No Need to Argue. Featuring two major worldwide hits (“Zombie” and “Ode to My Family”) alongside a varied yet unerringly strong collection of 11 other songs, the album changed the fortunes of the quartet from Limerick. Eventually selling more than 7 million units in the U.S., No Need to Argue represented a watershed in the band’s history, and rapturous critical acclaim reinforced the Cranberries’ status as an important force in music. A new 30th anniversary expanded edition celebrates the album and its enduring legacy.

Dolores O’Riordan’s distinctive vocals are a signature of the Cranberries’ sound, but it would be the collective creative input of the whole group—O’Riordan plus guitarist Noel Hogan, bassist Mike Hogan, and drummer Fergal Lawler—that yielded music that would resonate and endure with listeners. The group’s sound was informed by contemporary influences–the Smiths and other postpunk acts—but also by Irish folk. Yet Lawler says there was never a conscious effort to sound a certain way, or to combine varied musical textures. “None of that was ever spoken about,” he says. “It was subliminal.”

More from Spin:

- Foo Fighters Reveal 80-Second Minor Threat Cover

- Kendrick, Tyler, Nas Jump Aboard Clipse Comeback Album

- Fishbone Still Have a Bone to Pick

The group’s working methods were organic, with plenty of give-and-take. The band had begun with another singer, continuing briefly as an instrumental trio before O’Riordan came on board. “Once Dolores joined, we’d give her a tape with the music, chords, whatever,” Lawler recalls, “and she’d come back a week later with lyrics, vocal melody, a string line. And we were like, ‘Okay, this is really going to work.’”

O’Riordan’s writing skillfully bridged personal and universal themes. Lawler concedes that Dolores didn’t like to explain her lyrics, preferring to let each listener develop his or her own sense of what the words meant to them. “It was enough that they liked the words,” he says.

Producer Stephen Street’s introduction to the Cranberries came through the band’s label, Island Records. He recalls the first time he saw the group onstage. “They were very nervous and they weren’t particularly great, to be honest,” he says. “But there was something there.” He listened to some of the group’s demo recordings, and was interested enough to schedule a test session. “It went great, and we got on really well,” Street says. All parties agreed that Street would produce what would become Everybody Else is Doing It, So Why Can’t We? “Stephen’s just a magician,” says Lawler. “He really clicked with the band from day one.”

That album was initially a slow seller, so much so that the band’s future on Island was uncertain. But Street explains that Denny Cordell—the executive who had signed the Cranberries to Island America—persisted in promoting the group even after its two advance singles had been “pretty much ignored” in the U.K. “When the album came out, they couldn’t get any media or press because that had all gone on months previously,” he says. But Cordell convinced MTV to add the band’s music videos to its playlist.

At the same time, college radio—a major force in breaking alternative artists of the era—picked up on the band. “So all of a sudden,” Street says with a smile, “this band who are on the cusp of being dropped by Island Records got a phone call: ‘You’re happening in America; you’d better get over here.’”

The Cranberries embarked on a heavy touring schedule in support of Everybody Else. “They worked really hard that year,” Street says. “Because they knew that they finally had a chance, and they weren’t going to let that drop.”

Buoyed by the success of two hit singles—“Dreams” and the worldwide smash “Linger”—the Cranberries’ debut album would earn Platinum status in five countries, selling 3.2 million units in the U.S. alone. It was an auspicious beginning. “And it was the start of a very long and very fruitful working relationship,” Street says.

The Cranberries’ hard work on the road paid off in more ways than one. The group that reconvened in the studio in November 1993 was greatly changed from the band of just a year before. “The main thing was that they’d done so much playing that they’d become much better musicians,” Street says. He emphasizes that the group members had hit their stride. “We went in feeling quite committed and bold: ‘No, we’re not gonna listen to anyone. We’re gonna just do what we really want to do.’ And that really felt strong.”

“We showed up in the studio with most of the songs—apart from ‘No Need to Argue’—pretty much written,” Lawler recalls.

Initial sessions for what would become No Need to Argue commenced at the Magic Shop in New York City. Several of those recordings are featured as bonus tracks on the 30th anniversary release, and are noted as demos. Street diplomatically contests that notion. “They’re really alternate takes or works in progress,” he says, noting that the finished versions of those songs were often built upon the basic recordings made in NYC. “We recorded ‘Yeats’ Grave,’ ‘Everything I Said,’ ‘Empty,’ ‘Ridiculous Thoughts,’ and some others there.”

Street admits that he helped the musicians sharpen some of their skills and expand their musical vocabulary. “I helped Noel learn the ways of putting a capo on a guitar, and playing in different tunings.” But the band had arrived at the studio with well-developed ideas as to where the music should go. “One of the best things I love about the Cranberries is the ‘space’ that’s there in the music. There was a certain magic they had,” he says.

The sublime string arrangements on songs like “Empty” are among the album’s many strengths. O’Riordan and Street would explain their ideas to composer John Metcalfe, who would then “score it properly for a quartet,” the producer recalls. “There’s something really delicate there,” Street says, noting that No Need to Argue is ultimately a record of contrasts. “But some of the best records are, you know.”

Street says that no importance was placed on being able to replicate the album’s string parts in an eventual live setting. “That was great for the record,” he says. “If they wanted to play it live, they might have to work out a different way of playing it.” Lawler concurs. “When we were in the studio, it was like, ‘Let’s make these songs the best we can, and not worry about how we’ll do them live,’” he says.

Yet the band’s “live” feel in the studio was another important asset. Street notes that most artists today record with a click track to keep tempo rigidly consistent. Not so with the Cranberries. “If you listen to ‘Zombie,’” he says, “you can actually hear the tempo shifting, speeding up, slowing down. And that made it, really; that’s what has the energy in it. It’s wonderful.”

The album closes boldly with the serene and meditative title track, stripping down to only O’Riordan’s voice and a church organ. “I told them, ‘Guys, you’re not going to be on this one,’” Street recalls. “The boys were fine about it.”

The atmosphere in the studio was ebullient. “They were all really happy,” Street recalls. “Dolores was beginning to date Don [Burton], who became her husband. Everybody was in a really good place.” The band took a well-deserved break midway through the sessions, and at Street’s suggestion they all went skiing. O’Riordan took a fall on the slopes and suffered a severe injury that sidelined her for a while. “That didn’t go down very well with the record company,” Street says with a mordant chuckle.

Street and the band nevertheless finished recording and mixing at London’s Townhouse Studios. “It all fell into place really well,” he says. “The chemistry felt really good; we were firing on all cylinders.” Lawler agrees and says that he and his band mates “knew that the album was good; we were proud of what we had done.”

The upcoming album’s leadoff track, “Ode to My Family” was released as a single in the U.K. in November. In an unnerving replay of the previous release cycle, it performed only modestly on the charts. “But then there was this anomaly,” Street says. “‘Zombie’ came out, and it was unlike anything the band had done before.”

“Zombie” began to connect with listeners on radio and at concerts. “The rest,” Street says with a smile, “is history.”

Lawler notes that the Cranberries did encounter some initial pushback from their label, suggesting that “Zombie” was too controversial. “They thought it was too political, and that it might cause consternation if we released it as a single,” he says. He notes that the Cranberries had been featuring “Zombie” in their live show more than a year before it was recorded. “And it always got an incredible reaction,” he says. Even though those early audiences didn’t recognize the as-yet-unrecorded song, “by the time the second chorus came around, they were chanting the lyrics.” The band members stood their ground and Island released “Zombie” to worldwide success.

Highlights on the tour in support of No Need to Argue were many, but two dates stand out in Lawler’s memory. “I remember Woodstock ’94 like it was yesterday,” he says. “I walked out onstage thinking, ‘Jesus! I’ve never seen anything like this in my life!’ It was just a sea of people. We were looking at each other, [realizing] that it was a pinch-me moment. And we gave it our all.”

The yang to that yin was a free outdoor acoustic show in Washington D.C. “Loads more people turned up than anyone expected,” Lawler says. Crowds began pushing toward the stage, and the overwhelmed security staff made the decision to cancel the show; a riot ensued. “It was surreal,” Lawler says, noting another downside. “Nobody got hurt, but someone stole an acoustic guitar; that was not very nice.”

In addition to the original album, the new 30th anniversary edition of No Need to Argue features demos, early mixes, alternate tracks, and live material (including songs from the Woodstock gig and from a Liverpool concert). Chvrches’ Iain Cook, a longtime Cranberries fan created remarkable remixes of two album tracks, “Zombie” and “Ode to My Family.”

“My goal was to bring a fresh and somewhat personal perspective to some very well-known songs,” Cook explains. “It was important to me to take things apart and put them together in a way that sounds surprising and exciting.” He was guided by an important principle: “to be as respectful as possible, especially to Dolores’s vocals, while still pushing things a bit outside of the comfort zone.” Lawler consulted on the mixes, and Cook was delighted with his perspective. “I was sort of looking for some direction from him, some flags of things to avoid, but he graciously said, ‘Go for it and have fun!’ It was really fun working with Fergal; his encouragement and honesty throughout was refreshing.”

Cook reflects on the Cranberries’ legacy. “The songwriting is on a very different level to almost all of the indie bands around at the time,” he observes. “It’s never folky per se, but there’s a flavor that’s always there. And just as importantly, Dolores’s singing was quite unlike anyone else. There was so much purity and authenticity in every word; she put herself so completely into her performance. That’s a difficult and brave thing to do. I think that’s a huge part of the reason why their music connects so deeply and universally.”

Fergal Lawler believes the breakout success of No Need to Argue was the product of “everything happening at the right time. The record company worked really hard, and we toured hard.” Pausing a beat, he laughs and adds a closing remark. “If No Need to Argue was a shite album,” he says, “none of that work would have made a difference.”

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.