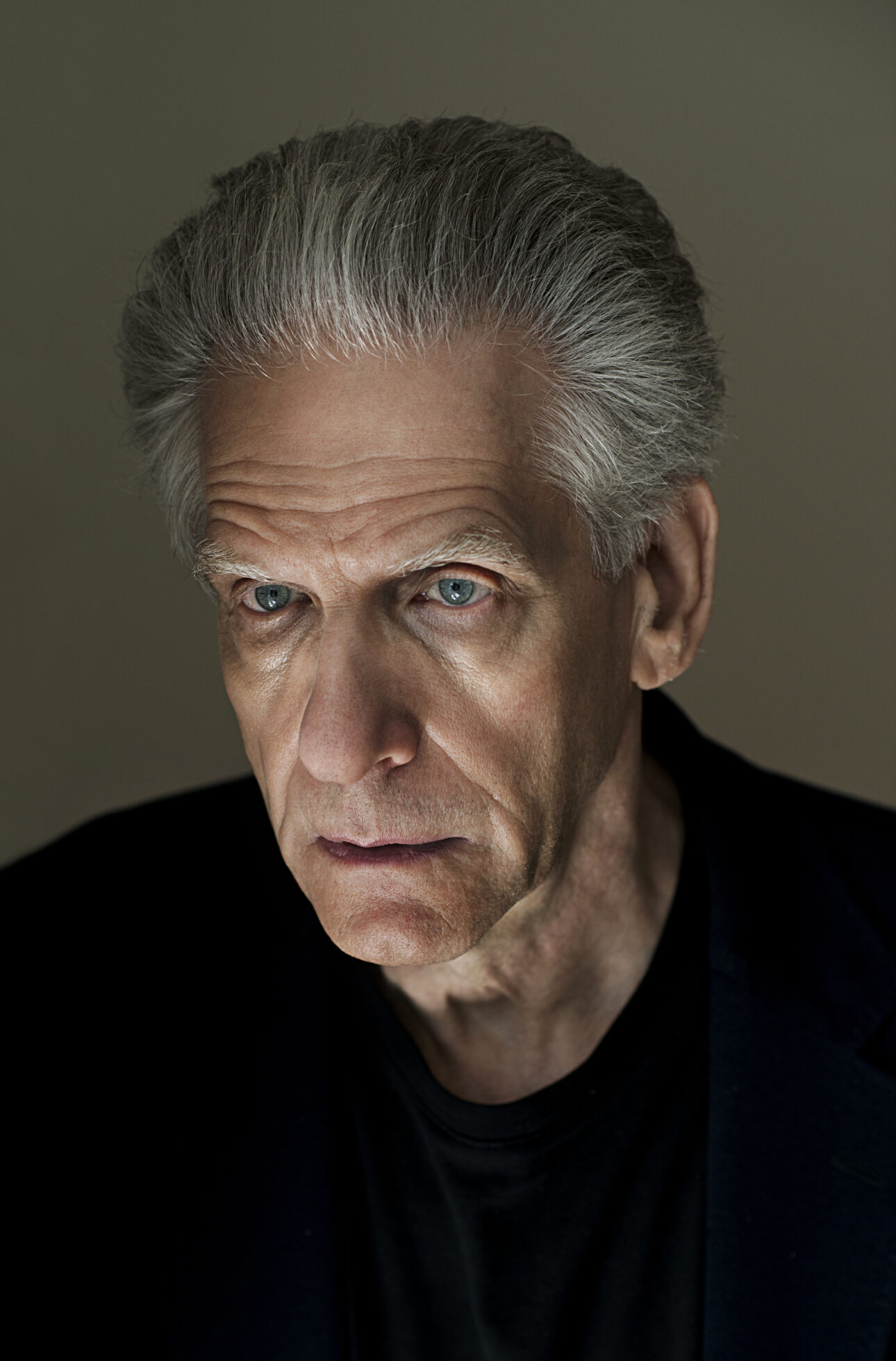

Death is an old and familiar concept in the films of David Cronenberg. There have been many casualties from murder, disease, and misadventure in his 50 years as a director, exploring grim corners of psychological and biological horror, crime, and madness. His newest film, The Shrouds, considers the aftermath of death and where grief can lead those left behind.

More from Spin:

- Circle Jerks’ Keith Morris Says It’s Time They Put Out a ‘Fuckin’ Ripper’

- Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame Welcomes Soundgarden, Outkast, White Stripes

- Ray Vaughn: Cutting Through the Beat

“How dark are you willing to go?” asks the film’s lead character, Karsh, a high-tech entrepreneur whose grief leads him to create a cemetery called GraveTech where cameras allow mourners to watch their loved ones decay in the grave.

The Shrouds was inspired by the 2017 death of Cronenberg’s wife of 43 years, Carolyn, at age 66 from cancer. In the film, Karsh (played by Vincent Cassel) expresses the impulse to crawl into the coffin with his dead spouse. It’s a moment taken from real life. “It certainly was my instinct,” Cronenberg says. “That’s where it came from. But I certainly cannot believe that I’m the only person to have experienced it.”

During his wife’s long illness and for years after her death, Cronenberg made no feature films, his grief contributing to the eight-year gap between 2014’s Maps to the Stars and 2022’s Crimes of the Future. But in 2021, he contemplated his own demise in the eerie one-minute short The Death of David Cronenberg, made with his daughter Caitlin.

“If you live long enough, you will have deaths in your family and deaths within your friendships, and you will deal with various kinds of grief,” says Cronenberg, dressed in black and speaking via Zoom from Toronto. “Many people first experience grief with the death of a pet, and it’s real grief. So it’s an innate part of being a human being. I’m certainly not unique, and in terms of art, love and death are the big subjects.”

The Shrouds saw a limited release in New York and Los Angeles before going nationwide on April 25. The filmmaker first imagined it as a series for Netflix, which funded the writing of two episodes before walking away. A feature film emerged from those early scripts.

At the film’s emotional center is Karsh’s late wife, Becca, portrayed by Diane Kruger (who also plays her look-alike sister Terry and voices a computer-animated AI assistant named Hunny).

“I’ve watched his films and known about him even before I was an actress. He traumatized me with The Fly when I was very young,” Kruger says in a phone interview. “When I read the script, I didn’t know it was based on the passing of his wife. I remember thinking this is a little different from what he usually does because it is very emotional. Most of his films have this odd detachment. I was really intrigued.”

For Cronenberg, grief in a different form was the inspiration behind an early film, 1979’s The Brood, which is partly about a man seeing his wife absorbed into a cult-like psychotherapy group, before bearing a brood of mutant murderous children. “The Brood was about a different kind of grief—a divorce—and it was induced by my very painful divorce that I experienced,” he explains. “Divorce, I’m sure many people could tell you, is a kind of death and a kind of grief.”

The filmmaker notes that the grief of divorce is also represented in The Shrouds through the character of computer whiz Maury (Guy Pearce), who longs to reunite with his estranged wife—the surviving sister of Karsh’s late wife. In the film, Maury refers to himself and Karsh as “brothers in sorrow.”

It’s hard to miss a surface resemblance between Cronenberg and Cassel as the character of Karsh, both lean with thick gray hair brushed back. The apparent cinematic doppelganger is coincidental, he insists, though Cassel did slow his speech pattern closer to Cronenberg’s calmer cadence. “I don’t look anything like Vincent Cassel,” the director says, running his fingers through his hair. “I think it’s the hair that’s done it. I’ve jokingly but truthfully said, I didn’t cast Vince because of his hair. If he had come to me with a shaved head, I still would’ve cast him.

“Once you start writing the characters, they become fictional,” he adds, drawing a line between his real life and the film. “It’s not like a documentary of my life. You need that distance. There might have been lines of dialogue that were actually spoken by you under certain circumstances or so on, but you really want your characters to come alive and to surprise you and to say things that you didn’t expect them to say. And then, of course, the actors bring a whole other level of reality to these characters. So it becomes fiction. The truth is, the fact that a film is based on reality does not automatically make it a good film.”

By the end of the 1970s, Cronenberg had built a reputation as a dynamic young horror filmmaker, creating a genre of his own ultimately known as “body horror” through scenes of explicit violence, disease, insanity, and exploding heads. It was a niche of extremes, and it looked to many like a place the director would remain indefinitely, like a next-generation Dario Argento or George Romero.

In 1981, his Scanners was a further evolution of that genre, following a series of low-budget shockers like 1977’s Rabid and The Brood. But Cronenberg never saw himself in such a narrow lane, and the success of Scanners (a No. 1 hit at the box office) opened up other possibilities.

“This was a little cheap sci-fi movie from Canada, from somebody nobody had ever heard of,” Cronenberg recalls with a smile. “So it was a big deal. It did bring a lot of interest and it helped me to finance my next couple of movies. So it was a high point.”

His next film, 1983’s Videodrome enjoyed a higher profile, with a cast led by James Woods and Debbie Harry, then at the height of her fame in the band Blondie. The same year, he released The Dead Zone, still remembered as one of the very best adaptations of a Stephen King novel. And then with the hugely successful 1986 remake of The Fly, reimagined as a story of tragedy and decay in the early AIDS era, with Jeff Goldblum as the human/insect mutation nicknamed “Brundlefly,” Cronenberg became acknowledged as a distinctive hit-making auteur.

Even that barely hinted at what was to come, with the 1996 erotic car smash-up movie Crash, and the intense crime dramas A History of Violence and Eastern Promises. The traditional horror elements were gone, though these films maintained a startling realism in scenes of violence. His evolution might have surprised fans of his initial horror work.

“I always thought of myself as an art filmmaker,” says Cronenberg, who found early inspiration in the New York film underground and the likes of Jonas Mekas. “I really thought of myself as more in the lines of Bergman maybe, or Fellini. Not that I had the scope that they had at that time. I could write original scripts that were viable films that could get financed and could get an audience. I felt that that was a strength that not all directors had. The French culture of Godard and Truffaut was that if you were an auteur—an author as a filmmaker—you would write your own script. But of course not all directors can write. I felt that I could do that and be part of that.”

To some critics, The Shrouds represents a welcome return to some of his early themes and content, particularly in the idea that bereaved survivors would choose the horror and strange comfort of watching as your loved one decomposes in high-definition.

“It’s not something I would choose for myself or for anyone I love, but I understand the concept,” says Kruger. “Very early on, David said the worst part was for [his wife] to be alone in death in this coffin. I never thought about it that way and it made so much sense.”

Karsh’s answer to that impulse is to create the “shrouds,” which are like a wrap-around camera for the dearly departed in the ground. After the graves are vandalized, and mysterious growths are found on Becca’s remains, the story spirals into conspiracies, paranoia, and hints at betrayal.

“If you’re an atheist, you’re not thinking, ‘Okay, she’s buried and I’ll see her in heaven,’” Cronenberg explains. “You can’t say that because you don’t believe that. You don’t want to let go of her. And in particular, you don’t want to let go of her physicality. You can’t really get in the box with her, although you have that impulse, because, of course, you would die.”

Karsh has found the next best thing, which is to watch her in the grave just as he had watched her in life. “A person you live with, you’re constantly observing each other. Not to judge, but just to observe and to enjoy the observation,” says the director. “So this is to say, ‘I want to continue to observe,’ and I’m willing to accept that it’s not going to be most people’s idea of a pleasant thing.”

Making the film didn’t make the grief go away or even diminish it for Cronenberg, but it was a way to channel those feelings and ideas into a creative direction. In his dreams, Karsh has visions of his late wife, both in idealized depictions of her in their bed, and then through various stages of disease, including amputation of body parts and surgical scars. Those scenes are jarring and deeply emotional.

“For me that was the hardest part of the movie,” says Kruger. “For me to do those scenes and to be nude plus have your body eaten alive by that illness, I felt very vulnerable, I have to be honest. It was not the most pleasant. I felt very raw.” There was also the added layer of knowing that Cronenberg was himself observing the scene from his monitor in the next room, “rewatching or reliving very intimate things” similar to what he’d experienced with his wife.

Kruger says she felt a responsibility to portray Becca in a way that reflected how Cronenberg had described his late wife. “David never put that on me,” she says. “He didn’t put any pressure on me to be true to people who had lived because [the movie’s characters are] not that close. But I wanted to capture that essence and their love so I put a lot of pressure on myself.”

Karsh’s visions of his dead wife were essential, she adds. “Those scenes with Vincent in the bedroom, they had to be really deep and convey the sense that they had been living their whole life together,” she says.

Cronenberg cast the German-born Kruger as Becca as part of an international cast to reflect the film’s Canada/European Union co-production. One of her previous performances in particular struck him: 2017’s In the Fade, where she stars as a grieving wife and mother whose family is killed in a terrorist bombing, and follows her journey toward acceptance and revenge.

“I thought she was superb in that, and I had seen her in some other things,” says the director. “Part of directing is casting. If you can cast the movie perfectly, you are halfway there to a great performance.”

While critically acclaimed, with several box office successes, much of his work has been considered too disturbing to be fully embraced by the Hollywood establishment. He’s never been nominated for an Academy Award, though The Fly won for special effects and various cast and crew from other films received nominations. Cronenberg says he remembers being at Cannes with A History of Violence in competition and the head of the jury telling him, “If this was a genre film festival, your film would’ve won the Palme d’Or. But it’s not a genre film festival.”

Even so, a new generation of body horror directors have emerged with notable films in recent years: Coralie Fargeat’s The Substance and Julia Ducournau’s Titane (which won the Palme d’Or in 2021). “I honestly don’t think about legacy at all,” Cronenberg says, but he’s met both directors, and feels a genuine kinship. “It feels like they’re like my cinematic daughters or something, you know? The fact that your work could be an inspiration, or a model for other filmmakers is really a lovely thing. It attests to the strength of what you’re doing and the force of it.”

With The Shrouds already receiving wide acclaim, some recent reports have suggested it could be his final film. But at 82, he doesn’t sound quite ready to retire, and is now considering translating his only novel, 2014’s Consumed, into a film.

“For the last four or five films I kept thinking they might be my last film, but I’m not alone in that. I think Soderberg has done his last film for 10 films,” Cronenberg says with a laugh. “It’s hard making movies. It’s difficult, and if you’re an independent filmmaker, getting them financed is a pain. But the impulse to be creative and to be creative cinematically, because that’s your art form, is still very strong. Of course, there’s the age question. Am I too old? Because it takes a lot out of you, a lot of stamina and a lot of focus, but [making The Shrouds], I didn’t find that physically, intellectually, or mentally that draining. It felt normal to me. So the chances are that I will continue to make films if I am still alive.”

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.