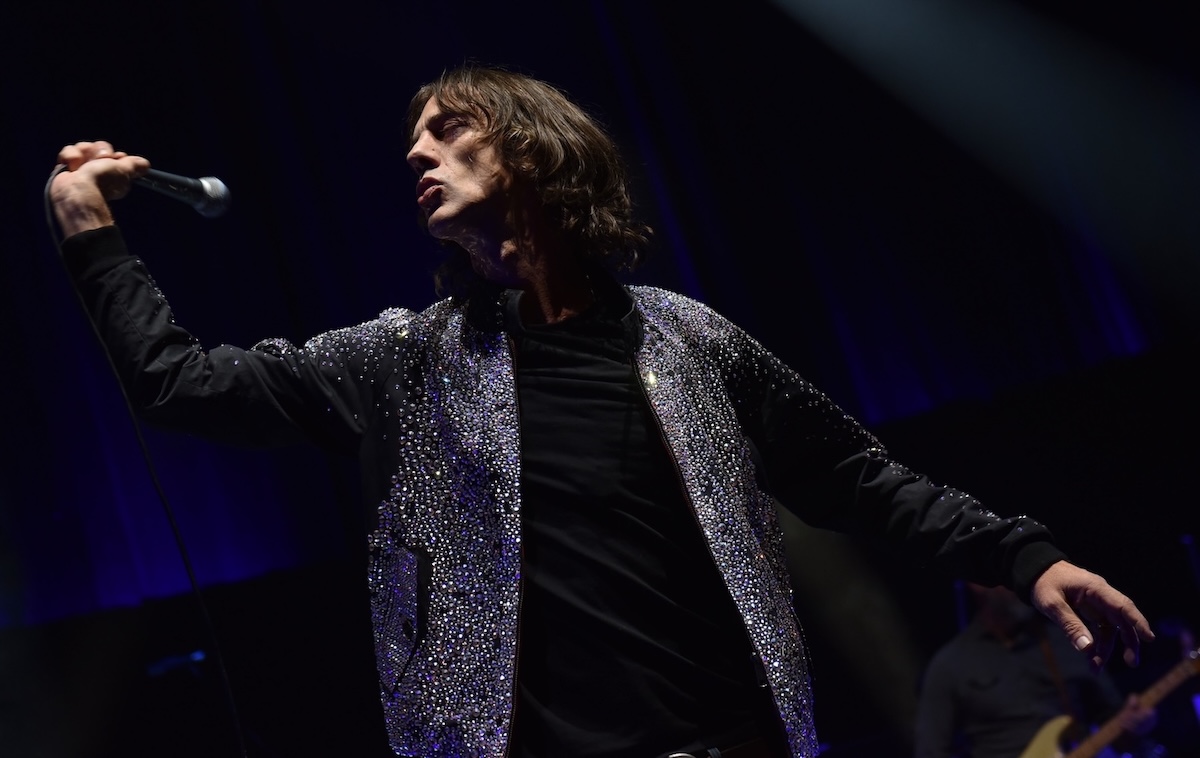

Richard Ashcroft is always dressed for the occasion. When he appears on my screen from his home in the U.K., he’s wearing a leather jacket with a sheen to it and the requisite shades covering a third of his face. He has an instinct for wardrobe that makes for vivid descriptions.

The last time I interviewed the Verve’s one-time frontman in person was 25 years ago, in a New York hotel room at 8:00 a.m. for his debut solo album, Alone With Everybody. He was wearing a crushed velvet jacket whose rich jewel tones dazzled me. Shortly after, I bumped into him in the lobby, his 4-week-old son strapped to his chest, the velvet discarded for jeans and a khaki coat—sensible dad clothes. His child, Sonny, was such a freshie his eyes didn’t focus yet. The other week, walking past the newsstand outside Los Angeles’ Book Soup, I was stopped in my tracks by the cover of Tatler featuring Sonny posing with Liam Gallagher’s eldest daughter, Molly. If I had any delusions about not aging, that striking image set me straight.

“Kids almost accelerate the passing of time, it’s bizarre,” Ashcroft acknowledges when I share this story with him. “It’s nice to see him grow into a good man, both of them.”

While Ashcroft’s public image is that of the ultimate rock star of unreachable proportions, he’s kept his home life with wife Kate Radley (formerly of Spiritualized) and their two sons very stable. He says he took the whole family with him on tour and, once the kids were school age, booked his music around their schedules. Following in his father’s formidable footsteps, Sonny already has a full album of songs ready to go.

“This is a tough game,” Ashcroft says of the music business. “When you’ve been doing it for 30 years, you realize the thick skin and hard heart you sometimes need to employ. It’s a toll on people. But I’m still with my wife, and the kids still live here. We’re together as a family, so it was worth it.”

It’s still worth it: Ashcroft has a new album, his seventh solo, Lovin’ You. “Eclectic” is the catch-all phrase for Lovin’ You, which sees him back to his sampling ways, lifting a choice tidbit from Joan Armatrading’s “Love and Affection” for the smashing lead single, “Lover.” At the other end of the spectrum is the stripped-back, twangy “Out of These Blues.” The album moves between these extremes, balancing studio craft with acoustic textures. At its core are Ashcroft’s unimpeachable songs, whose staying power is undeniable. He worked closely with guitarist Steve Wyreman and co-produced the record with longtime collaborator Chris Potter and Emre Ramazanoglu, with a special appearance by Madonna’s old cohort, Mirwais, on the dancefloor-focused “I’m a Rebel.” His voice remains soul-dripping, hitting heart-wrenching notes on “Oh L’Amour” and rock ’n roll heights on “Heavy News.”

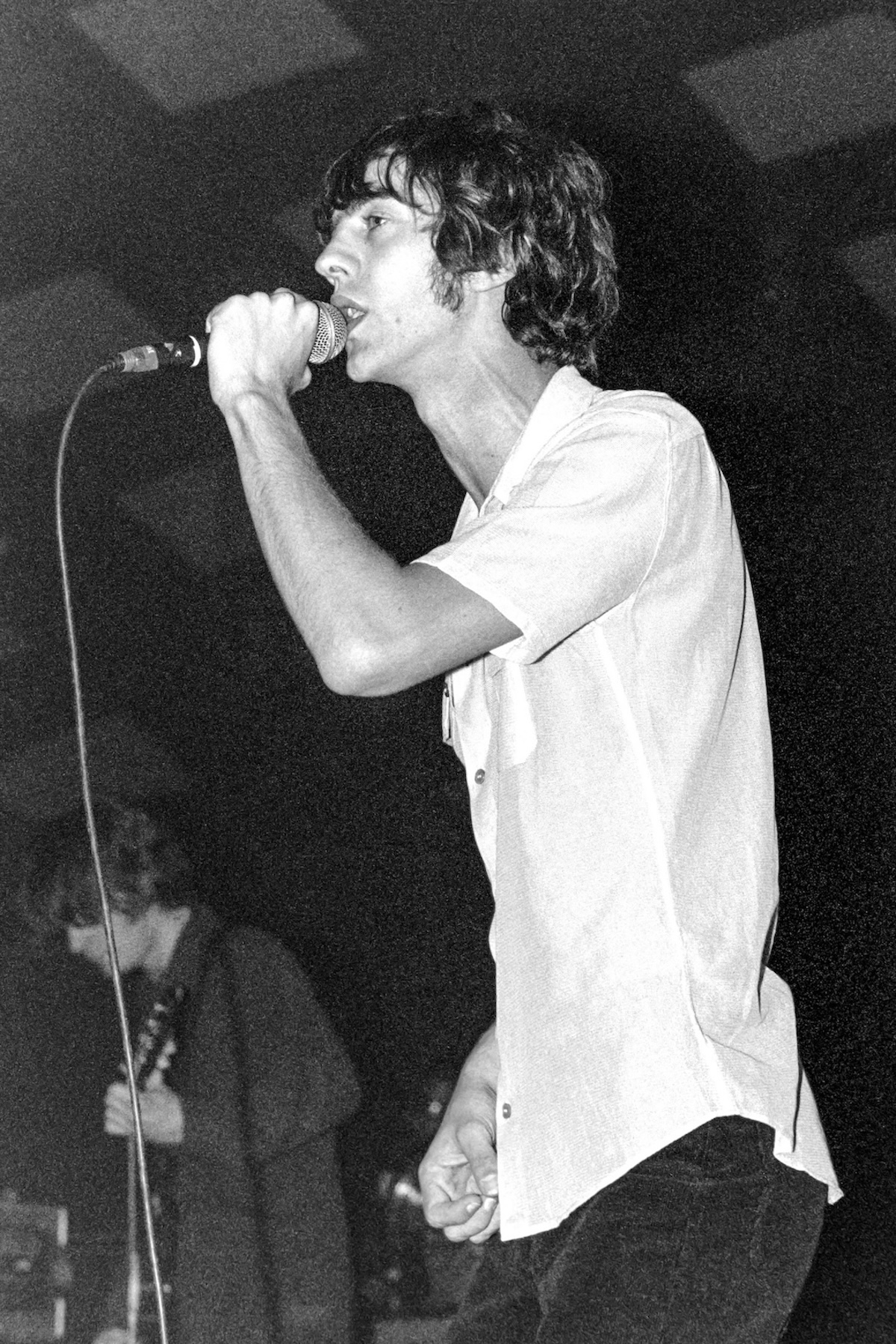

Fresh off opening for Oasis on the U.K. dates of the Live ’25 Tour, Ashcroft is mentally preparing for his own U.K. arena run next year, teased with a single date at Manchester’s Co-op Live in November. For now, though, he’s on a roll—speaking for 52 minutes straight without me asking him a single question. His words are gold, just as valuable now as when I first interviewed him more than 30 years ago, at the time of the Verve’s debut album, A Storm in Heaven. He was barely in his 20s, but even then, he carried an instinctual, prescient knowledge. I had no idea what he was talking about, but as the years rolled on, I began noticing things he’d shared with me coming to pass. I thought of him every time this happened, and each opportunity I had to interview him afterward, I asked him to tell me what he saw in the crystal ball in his head—including this one.

On Staying the Course

I’ve been doing this since I was 19. There’s not that many of my peers, contemporaries from the time, that are still in the game. It can destroy you. I think I learned to enjoy the fight. Instead of obsessing over the negativity. You try and be more like an athlete. It becomes, “How do you internalize that and use it to your advantage? Keep you going, keep you on the path of creativity?” It’s tough, because there are always commercial factors.

I’m a populist. I love the idea that “Bitter Sweet Symphony” became so huge, and yet it’s a brutal song about the reality of life, but it’s packaged in a way that is universal. People probably aren’t even analyzing what the lyrics are saying. For me, that’s the ultimate achievement.

On Inspiration

It’s such a beautiful thing to have some of my contemporaries [Oasis] doing so well. It gives you a fresh lease of energy. It’s a bit like when I saw Mick Jagger a few years ago. It was just like, “Man, you’re doing stuff I couldn’t do now.” You could be cynical, but ultimately, if you see the Stones, you’re left with a feeling of joy. This guy’s 30 years older than me, but he’s a phenomenon. The whole band is. You get these moments in life where it gives you that extra bit of inspiration and energy.

Creative people, we’re one step from never being seen again. I did that once, for five years. No interviews, no records, no nothing. I thought that was that. But then you get these moments like playing with the Stones or this Oasis thing and suddenly your camel hump gets stored with inspiration, and now I got this new album out.

On Returning

I’m already planning my next thing. With the kids grown up now, I’m really wanting to take these next few years and take it forward. In England, the gigs I’m going to do next year as a solo artist are the biggest arenas you can play in my own country. You got to make it in your own backyard before you can start trying to push it in other places. Respect from your own country and your own people is important. People are looking back on what I’ve done, and they’re appreciating where I’ve been coming all this time.

I’ve been called, as you know, mad from the age of 20. But I think a lot of the sentiments of the things I’ve been into, they feel more relevant now than they did back then. People are getting that now. It’s quite exciting times, because I don’t even feel like I’ve been fully respected, or appreciated, as a songwriter or a performer. What happened to me was what happens when great people go solo. You’ve built up Coca-Cola. We used to have this drink called Panda Shandy, quite a cheap can in England, and now you’re Panda Shandy. Your name doesn’t have the same resonance at all.

On the Super Bowl Placement

The gap between a certain amount of success and something becoming globally big is absolutely huge. When Urban Hymns came out, MTV as a music channel was still influential. You’ve got your video out every single day. We didn’t want Nike using “Bitter Sweet,” but we had no say over it, and Nike used it in the Super Bowl ad. The next week, you’re selling 100,000.

But I remember at the time thinking, “All those interviews I did as a kid in America every day on tour in the early ’90s, was it really worth getting up at 7 in the morning getting driven to some college campus that you probably couldn’t tune into a quarter of a mile down the road to what I was saying?” That got obliterated. In the early ’90s, we were still in that idea of consistently touring America, doing interviews, building up this fanbase, blah-blah-blah. But then you realize big success, sometimes it’s out of your hands.

On America

I’m back to pre-Urban Hymns in America. America has got some of the biggest stars and biggest talent in the world, always has. You’re competing against that. To even make a dent there at any point in your career is pretty amazing. The odds are stacked firmly against you if you’re not from there. And then, of course, if you ever do achieve any kind of greatness and size, that’s going to be with you. It’s a gift and a curse.

The irony was that Urban Hymns was supposed to be my first solo album. A couple of the guys of the Verve, Simon and Pete, bass and drums, were carrying on regardless, with me. Out of fear and insecurity and feeling of unfinished business, I made a call to Nick [McCabe, the Verve’s guitarist] and it became this Verve thing. Then it becomes so huge.

Then to start off on your own, with your birth name, which isn’t Elvis, it’s just Richard Ashcroft. If you stick around long enough, things come through in the end. If you’re writing stuff and involved in things that have a little bit of a timeless quality, that have some depth, people start discovering it. That’s where I’m at right now.

On Oasis

When I play with Oasis, you’re getting “Bitter Sweet, “Drugs Don’t Work,” “Sonnet,” all the songs I’ve written that mean something to people—and that’s before Oasis have even played a note. Before Oasis were getting on the stage, you just heard the last refrain of “Bitter Sweet Symphony.” It’s something really special. It’s unusual and it’s rare.

I’m not sure what your vans are called over there, but it’s called a Ford Transit over here. It’s this classic early tour van that every band uses. They were in a Transit, and we were in a Transit. We’d already put an album out. Oasis supported us on a few shows. We wanted to be the Stone Roses. And I think that was a bit like Oasis. They were such a pivotal influence over our generation. When we first played with Oasis, it was like, wow, the first people that had my kind of ambition. My ambition was always seen as an arrogance thing, but it really wasn’t. I was the voice of the band and I took my influences from boxing promoters. When I met those guys, it was like, “Ahhh, you’re on a similar tip to me. You dream big. You want to be the biggest band in the world. You want to write classics.”

On Songwriting

Time is incredible. It really opened my eyes this last summer, not only to [Oasis’] thing, but my thing. It’s like, wow, these things really have lasted, and they really mean so much to people on an emotional, deep, visceral level. As a songwriter, a performer, you can’t really wish for anything other than that. That’s the ultimate dream: to connect with people, and to see people connecting. To see a whole Wembley Stadium singing my song back to me, and they haven’t even paid their hard-earned money for me—I was put on way after these things sold out in two minutes—that’s just an incredible feeling.

It really has made me sit back and think—not that I’m going to try and recreate anything like that, but I will, as a more mature man, try and reflect in the future where I’m at and where we’re at in a way that really hits in an immediate, human way. We are at that crossroads—and this summer’s proved that as well—we’re at an incredible, unique place in history where we could lose so much so quickly. I felt this summer was about this unbelievable yearning not just hand that over, that real human coming together thing when we’re so fractured as societies.

On Unity

Concerts, for me, you leave whatever at the door and come together in this place and celebrate this moment together, no matter what your religious or political beliefs are. Playing Glasgow I realized, “Wow, those front X amount of rows, they might live in communities and never, ever share time with each other, maybe just on religious grounds or football. They’re divided.” These concerts are a moment for everyone to forget that. It’s the same around the world. Concerts are sacred places where music is the conduit to bring people together. It’s not about ostracizing people all the time.

I consider myself a punter to culture. I don’t feel myself hovering over it or looking down on it. I like trash. I like high art. I like it all. But we’ve become a time where things have become so fractured that we forgot that space, the concert, that’s a sacred space for us to come together. We’re about to enter an AI technocracy madness that none of us can even really get our heads around. But at the same time, look at this outpouring of emotion from people watching a band, watching drums, bass guitars, singing melodies. It’s so basic and simple but it’s so powerful. It’s one that maybe can be analyzed in a decade’s time. What was that all about? Why was it like that?

Oasis have always had an amazing fan base, but there was something different. It was uplifting, and it brought people together. I don’t think you can ask for more than that. That’s the most powerful statement you can make. If you bring people together, you’re dangerous. Because when people are together, they’re strong and they’re powerful. When they’re fractured, they become very weak. It was deeper than just gigs for me. There was something in the air that I don’t quite know how to explain yet.

On the New Album

It’s got a lot of the different sides of what I’ve been into over the years. It’s got my sampling elements. It’s got pretty stripped-back acoustic things. At one point I was going to make a very sample-based record. This is just before COVID hit and that put everything out of kilter. I kept some of the juiciest ideas from that project, and I thought, time’s catching up, and I’ve got these other songs that are a bit more classic. I’m just going to put it together. I’m not going to make a concept. I’m just going to pick some of my strong songs.

Last autumn, I got in my house, set up a little studio with my great guitarist, Steve Wyreman, and we laid down a bunch of songs. Steve got a few Bay Area musicians involved. It would have been easy to look at what’s going on and make this doom-filled prophecy on the future. But I thought, my songs themselves, my titles, the lyrics, the feeling, they could be now. I wanted to create something static and beautiful. Something people could put on, and it crossed all boundaries. I love making songs that people can’t really nail. And I like making things, like the last song of the album, it could be a Velvet Underground stripped-back tune. It could have been made in the last 40, 50 years. There’s nothing truly innovative about it. But for me, if you’re around and you’re doing it, you’re modern. You could have a six-string acoustic. If you’re out there on that stage in 2025 you are modern. You’re a modernist. That’s just your angle, your take.

On Sampling

There’s always been a sample thing. My song “Music is Power” comes from a Curtis Mayfield track and obviously “Bitter Sweet.” I had a Bee Gees sample on United Nations of Sound. It’s interesting to start with the sample. It gives you a fresh take on how to approach it. You want to take something like “Love and Affection,” Joan Armatrading, an iconic moment in that song. But I’ve always loved early hip-hop in the sense that they found that nugget, and they just keep playing it. I’ve got that hip-hop mind as far as tracks are concerned. Maybe in the future I’d be a good producer or remixer, finding the nugget in people’s tunes, that seam of gold I want to hear over and over again. It’s not a case of just mumbling over the top. It’s how do you construct something over this that sounds fresh? Then all the bullshit that surrounds it, and the difficulty of clearance, it was like, if I’m going to do 10 of these, this is going to take years before we’ve got the clearance on everything. With my history, I’ve got to make sure that everything’s above board and cleared, and everyone’s happy.

So I put the brakes on just an album of samples and thought, I wanted it to be quite eclectic and show different sides of where I’ve been over the years. There is some heavy songs on there, but I wanted to have different facets of the human condition, not just one. We all have the potential for deep introspection, for depression, for love and ecstasy.

On the Future

We’ve never lived in an exponential curve. Maybe when I was talking back then, it was a soft climb that you could process. But it’s difficult for someone like me to process exponential change, because it’s running away with itself at such a rate.

Like I said with the concerts over the summer, the pendulum may swing one way, but we are still human, and that energy and that spirit will fight the change. In 1984 there’s a flat screen TV in everyone’s home. The idea was that the state would force you into this. We’ve lived through a period where we’ve willfully desired the very thing that all those years ago would have to come from the top down, forced on us. It’s going to be a rocky period because there’s going to be a section of society that will walk into this willingly. They will save up and buy the next piece of enslavement. But there will be a huge chunk of people that have some distant memory of a different way. This is going to be the next spiritual fight along the way.

It’s the battle for the mind. Control is the key word. How you control people when people are in fear is a lot easier when you have these mass surveillance security systems being made where you know we’re almost in a Minority Report-type situation. Often things can be packaged with such doom-laden wrapping that you don’t want to move forward into this reality. But we make our reality, and I think there is enough people out there that are aware of this that the balance could go in our favor.

It’s just that with an exponential curve and things moving so quickly, it’s really difficult to imagine how, as a society, we’re going to deal with mass potential loss of jobs? When the human ear can’t differentiate between the AI Richard Ashcroft and Richard Ashcroft? When scripts are being written and they’re more profound, potentially, than the thing the dude’s written in Hollywood in his bungalow. Are we going to be able to define what’s human? What has a soul? We lost our soul. Are we going to lose our mind? Our freedom, speech, all of it’s under attack. You have to ask yourself, what is that? Did we leave such a big gaping hole? Did we lose our faith and lose our connection? When we lost that connection, what filled the void? Is it just desire for things? I’m a victim of that same as anyone else. I’ve bought some nice cars. I don’t swim, but at one point, I had two houses with swimming pools. But that’s rock and roll.