Puscifer is not like other bands. Not even like other bands fronted by the same man. Maynard James Keenan has spent the last three decades presiding over the muscular alt-metal of Tool and the inventive hard rock of A Perfect Circle—all of it to great success—but reveals a different side of himself as master of the Pusciverse.

With longtime collaborators, guitarist-producer Mat Mitchell and singer Carina Round, Keenan remains fiercely serious about the music in Puscifer, but it arrives wrapped in a wild cabaret of performance art, comedy, costumes, wigs, and hilariously bizarre characters.

Keenan marked his 60th birthday in April 2024 by launching Sessanta, a concert tour that extended into 2025 and brought together A Perfect Circle, Puscifer, and his friends in Primus on a single stage. All the musicians took turns performing, with a bottomless supply of “fun-size” candy within arm’s reach.

For anyone still uninitiated into Puscifer’s strange fantasia, the experience was a bewildering revelation.

“I think a lot of people had a couple questions,” Keenan says of the concerts. “People came to see A Perfect Circle or they came to see Primus, but walked away going, ‘What the fuck is this?’ They left with a whole new appreciation for this band they hadn’t heard of.”

Keenan is in a small dressing room at the Masonic Lodge at the Hollywood Forever Cemetery in Los Angeles. Sitting beside him are his Puscifer partners Mitchell and Round, all in black, assembled for a private playback of Puscifer’s new album, Normal Isn’t, in the venue’s 150-seat theater. In the lobby, guests mingle over Keenan’s Merkin Vineyards wine and plates from Danny Trejo’s taco shop.

As it happens, the cemetery is not far from the former site of Tantrum, a tiny improv comedy club in the early ’90s where Keenan—then fronting a still-obscure Tool—moonlighted among comics like Janeane Garofalo, David Cross, and Laura Milligan. It was there, in a sketch, that he first uttered the word “Puscifer.”

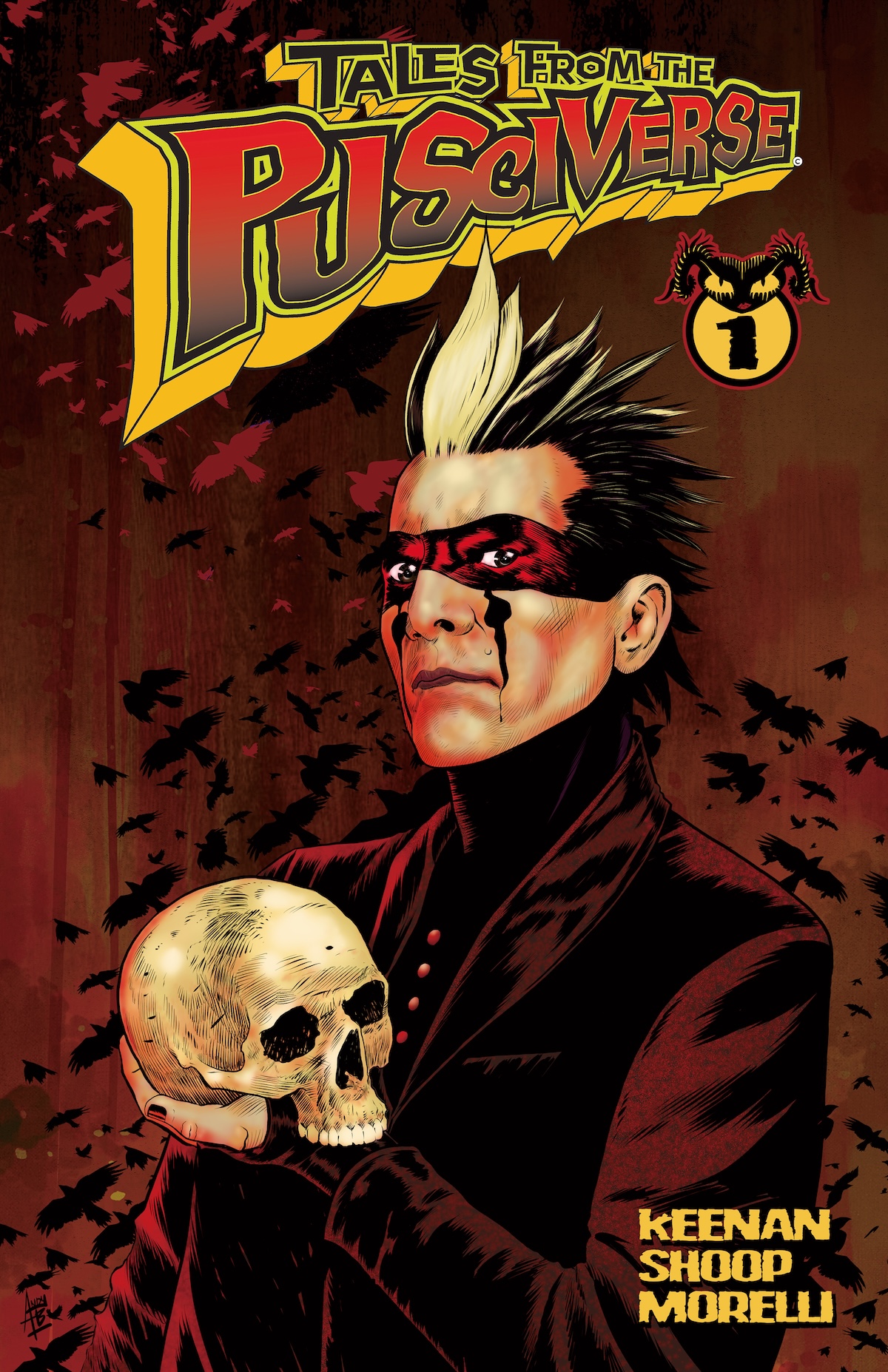

It took years for that grain of an idea to become a serious recording entity, but its strange cabaret beginnings are central to Puscifer’s DNA. Every incarnation of the band includes characters to play, from Keenan’s Major Douche and Special Agent Dick Merkin to a squad of masked lucha wrestlers. Their stories unfold through songs, video segments, and, most recently, a graphic novel, Tales From the Pusciverse.

Most bands don’t do this.

“I fucking love it. I’m an attention-whore drama queen,” says Round, who is introducing a new character named Fanny Grey. Turning to Keenan, she adds, “You get all excited every time there’s a tour and you write a character and you write some story, and now you’re trying to put them all together.”

“It’s not going well,” Keenan replies, laughing.

The humor is sharp, but the songs are not frivolous. Normal Isn’t is filled with the chaos and darkness of the modern world. The title song rejects the passive acceptance of the unacceptable, as Keenan sings, “All the damage / How’ve we managed for so long?”

“What we’re seeing now is not normal,” says Keenan. “We get desensitized: ‘Oh, there was another school shooting.’”

On the growling “Mantastic,” Keenan skewers the macho and pampered, unimpressed with tough talk and excessive male grooming. He bites hard on the absurd lyrics: “Mani pedi ending soon, then so will you … Can you smell what I’m spraying ’round?”

“I’m trying to imagine all the alpha male horseshit that’s been going on for a while,” Keenan explains. “I’m trying to imagine explaining manscaping to my 1978 wrestling coach—and all that goes into manscaping—and have him just look at me and go, ‘You need to go home for a week and you’re off the team.’”

Musically, the album rides a synthy, forceful groove that leans into the trio’s affection for ’80s new wave, goth, and post-punk. Mitchell often begins by constructing an edgy, melodic foundation in the band’s new warehouse studio in L.A. “A Public Stoning” opens with a lengthy, ominous bass intro before Keenan arrives with a furious rebuke: “Tunnel vision paranoia / Baking in your echo chamber!”

Throughout, Mitchell maintains the post-punk tradition of prominent basslines that prowl and provoke. “It’s interesting to have a guitar player play bass, because they tend to play it like you’re not supposed to,” says Keenan, who compares Mitchell’s work to other esteemed bassists—Tony Levin, Justin Chancellor, Greg Edwards—whose throbbing lines function as standalone melodies rather than simple foundations.

“We love a good beat. We love a good synth sound,” says Mitchell, known for embracing retro-future instruments like the Synclavier and Fairlight, among other vintage gear. “I like finding these things, fixing them, and generating sounds with them.”

There are other left-field flourishes. “Seven One” is dominated by narration delivered in an immaculate British voice. Keenan initially recruited Nine Inch Nails associate Atticus Ross, aiming for what he calls “the Oxford English vocal.” But after recording it, the London-born Ross suggested they call his father, Ian Ross. “We got his dad to do it,” Keenan says. “And it was perfect.”

Most tracks originated with Mitchell sending music to Round and Keenan, but their frontman, newly fluent with the Logic program, also initiated a few himself. He’d done the same thing when creating the special three-song Sessanta E.P.P.P., sending the rough sketch of a song to each act on that traveling festival.

“Everybody took them and ran with them,” says Keenan. “It was pretty cool to hear where they went.”

Puscifer’s last album, 2020’s Existential Reckoning, emerged during the first year of the pandemic, all touring plans cancelled. The video for “Apocalyptical” found bleak humor in a skateboarder in hazmat suit rolling through the empty streets of Los Angeles.

Dark times can lead to enlightening, hard-hitting music. For several songs on Normal Isn’t, Keenan sounds palpably irritated with humanity.

“I mean, just in general,” he admits, as Mitchell and Round laugh.

“I was around for the first Gulf War. I was almost in the first Gulf War,” Keenan goes on. He served in the U.S. Army for about two years in the 1980s, and was momentarily on course for a longer military career. “You just hear the same rhetoric.”

Bad news tends to reverberate through the generations. Keenan was just 6 years old, growing up in Ravenna, Ohio, when the massacre of students by National Guardsmen happened at nearby Kent State University in 1970. He had no awareness of it at the time, but the tragedy hung over the region (and the country) for years. One of his favorite bands, Devo, was born in the aftermath of that bloodshed.

“There’s something off about that area,” says Keenan, who suggests that feeding any sensitive kid that “combination of ingredients, you’re going to go the way of Chrissie Hynde, Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, and Devo. That’s going to affect you in some way. And if you’re even leaning toward art, that’s what you’re going to get.”

The present moment, Mitchell suggests, recalls the turbulence of the anti-war and civil rights era. Round adds, “With the added shit show of social media to polarize.

“The algorithms are just feeding you whatever you want to hear,” Keenan says, “to justify whatever actions you’re about to take.”

Puscifer will carry their messages into the open as they launch a U.S. tour beginning March 20 in Las Vegas. After that, Keenan will be back at his winery in Jerome, Arizona, for harvest season, and eventually to Tool and A Perfect Circle, whenever the time lines up.

“It’s just different conversations,” he says of his three music projects. For him, part of the fun is watching how far an original idea will go in their hands. “You can’t be precious about the thing you’re starting with. It’s all gonna grow organically from there.”