In the first season of her recording career, from 1974 to 1980, Patti Smith was a raw nerve, blazing behind the microphone on a mission to reinvent rock and roll as a setting for a new kind of feral, literary revolt.

She emerged from the first generation of punk rock at CBGB in New York City, alongside Television and the Ramones, back when that movement was more of an idea than a specific sound (or Spotify category). Yet Smith belonged to an older Bohemian tradition, from the hallucinatory poetry of Rimbaud to her Beat generation mentors Burroughs and Ginsberg—and, above all, Bob Dylan, her imaginary boyfriend when she was a teen: “There was no one I identified with more,” she writes.

What they shared was toughness and a revolutionary spirit, providing an uncompromising foundation for her debut album, Horses, now marking its 50th anniversary. No singer in that first wave of punk was more powerful or distinctive, but for her, the words always mattered most.

Smith, who turned 79 on December 30, just closed one eventful year and is beginning another. There was a recent run of concerts to celebrate the Horses anniversary and a new two-disc special edition; and an ongoing book tour in support of her newest memoir, Bread of Angels, another elegantly written volume that tells the story of that era and more.

Onstage, the years have only intensified the power of her delivery, her voice still fiery but somehow deeper, with the added weight of experience and earned wisdom. But even as she’s continued to tour through the years, she hasn’t released an album of new material since Banga in 2012. Her creative energies are now focused on writing.

From her days as a starving artist, Smith has written and published throughout her public life, emerging on the New York underground via chapbooks and collected poems. That all changed with her 2010 memoir Just Kids, winner of the National Book Award. On her Instagram page, she identifies herself not as a rocker but as a writer. It also assures visitors, “We are all alive together.”

She now balances those roles, with a homecoming event for Bread of Angels on January 21 at the Symphony Space in New York City, and more scheduled concert dates stretching across Ireland and Europe in 2026. She hardly seems to be slowing down.

The new book opens with memories of childhood: born in Chicago, moving with her family to Philadelphia, settling finally in South Jersey, as layers of awareness unfolded for her during seasons of fever and illness. She was a sickly but adventurous girl who daydreamed in class. A family outing to the Museum of Art in Philadelphia awakened her with “the revelation that human beings create art,” as she wrote in Just Kids. By 14, she had turned to books and rock and roll for salvation. She lit candles for Dylan after his infamous motorcycle accident in 1966, and discovered the “mystical language” of the French symbolist poet Arthur Rimbaud in 1967. Watching the Rolling Stones perform on “The Ed Sullivan Show” was a sexual awakening.

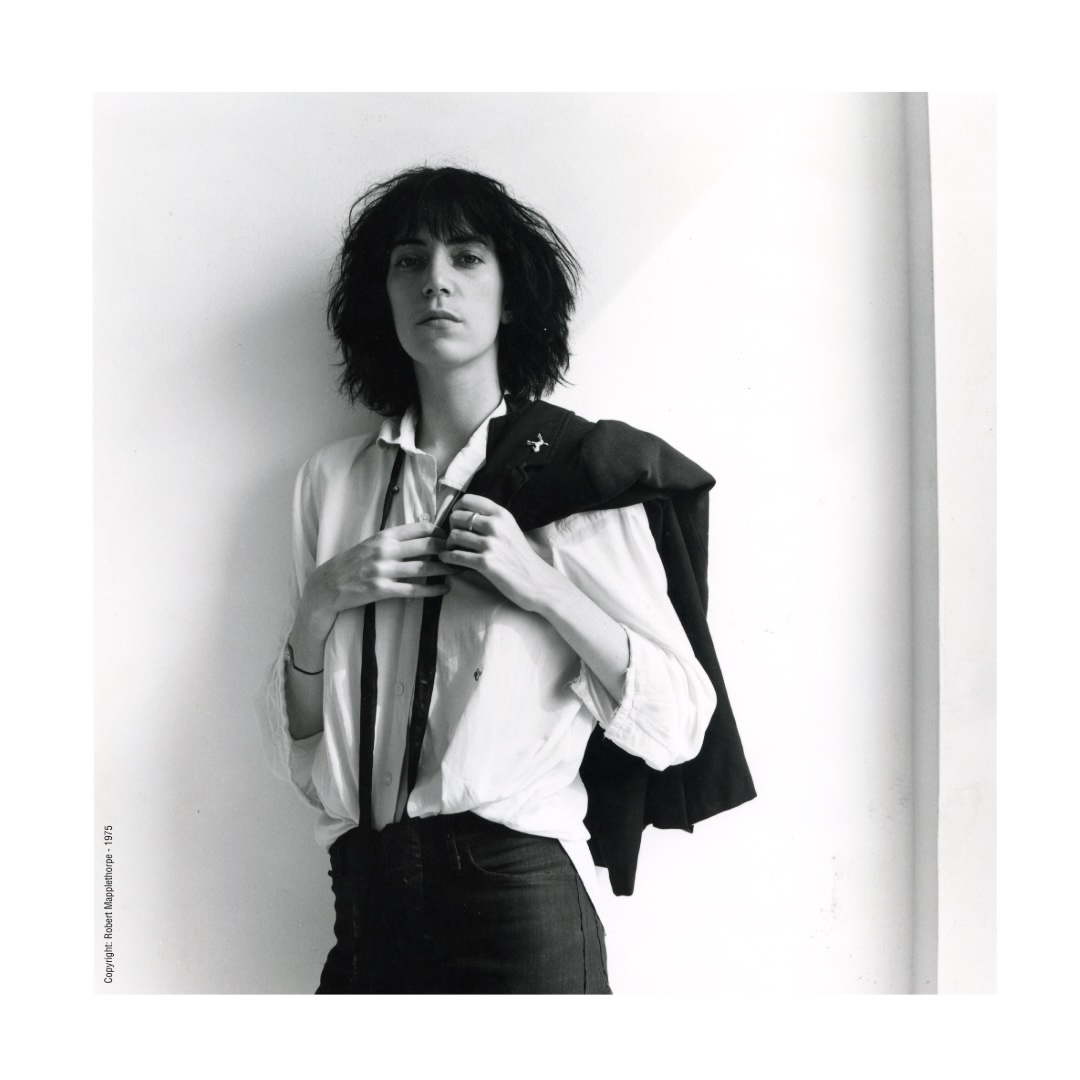

She came to New York in 1967, hungry to be a part of the Boho present, but already looking to the future. She was barely 20 when she met Robert Mapplethorpe, another young artist still years away from picking up a camera in a serious way. They soon became lovers, then confidantes as their paths diverged creatively and sexually. As she writes in Bread of Angels, she stepped off the bus with nothing but desire: “In choosing to be an artist I knew I would be on my own, yet still hoped for a compatriot, and providence led me to him.”

Their meeting was the essential miracle for both of them, as young artists adrift in a big city there to seduce and inform who they would become. Years before he famously photographed Smith for the cover of Horses, “I was a bad girl trying to be good and … he was a good boy trying to be bad,” she wrote of Mapplethorpe in Just Kids. Smith was the sickly one of the pair, and she turned out to be the survivor.

There were others: playwright Sam Shepard, who was the first to suggest that Smith have a guitarist accompany her poetry reading at St. Mark’s Church, and thus make her first step as a musical artist. He also gave her a 1931 Gibson acoustic that she named Bo. Dylan confidant Bobby Neuwirth encouraged Smith to write ballads. She was a young rebel amid a generation of “modern angels,” mingling with close friends like Jim Carroll, Allen Ginsberg, and William Burroughs.

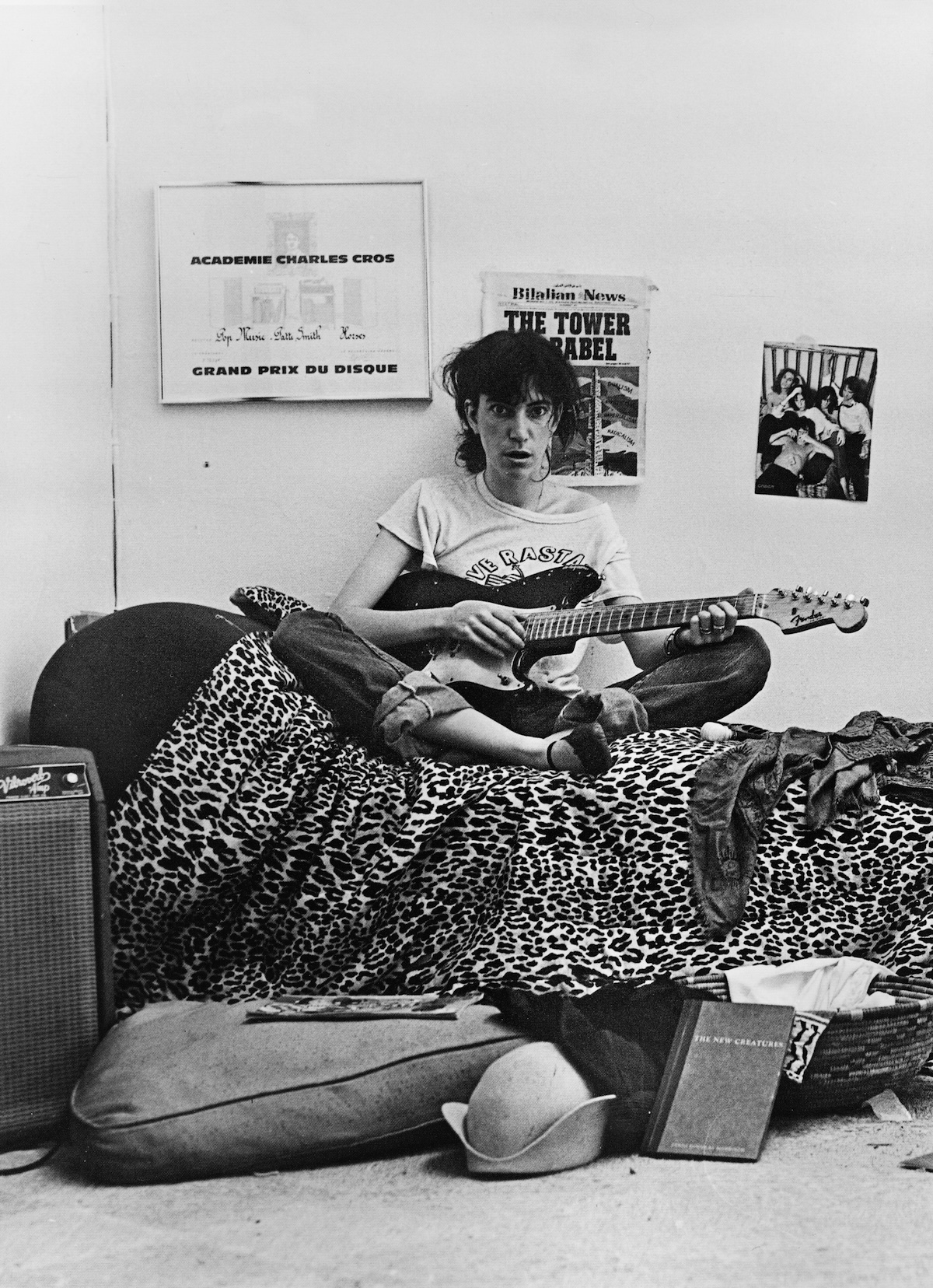

Smith lived an adventurous art life for years before Horses, and, with then-paramour Shepard, she co-wrote and co-starred in an off-Broadway play called Cowboy Mouth. To see pictures of young Patti in 1971, living at the Chelsea Hotel with Shepard and various folkies and Warhol luminaries, it’s clear she already embodied the artist she would become, even if she hadn’t yet put her poetry to music. Some of the poetry that eventually appeared on Horses originated from that time (“Redondo Beach,” “Oath,” etc.). By then rock and roll already meant everything. She was writing essays for Creem and Rolling Stone, always in celebration (of the Stones, Velvet Underground, Edgar Winter, sobbing at the grave of Jim Morrison).

In 1975, Smith’s band played New York City rock club The Bitter End, and it was their first time with a drummer, a true rock band at last. In the dressing room after, Dylan wandered in, asking around: “Any poets back here?” Smith, inexplicable even to herself, was so full of energy and attitude, and with no time for politeness, blurted out at her one true idol, “I hate poetry.” Dylan was amused.

It turned out they lived near each other on the same street in New York. Soon, Dylan was taking her to loft parties and other events, and she once watched him pick up a guitar to play some of his newest songs, destined for his album Desire. “Bob never seemed offended by anything I said, so I felt free to speak my mind,” she writes. She’d never stopped doing so, and when Dylan was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2016, it was Smith who performed “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” in his honor at the Stockholm ceremony.

Eventually, Smith was a charter member of a generation of “art rats” who took over a new dive called CBGB, along with the likes of Richard Hell and Blondie. For her, as she soon wrote to describe her debut Horses, the formula amounted to “three chords merged with the power of the word.”

She didn’t necessarily subscribe to the Clash’s musical call to arms: “No Elvis, Beatles, or the Rolling Stones in 1977!” For Smith, the new revolution owed something to the last one.

With a recording contract at Arista Records that allowed her complete creative freedom, Smith and her band began work on Horses at Jimi Hendrix’s Electric Lady Studios in Greenwich Village. As their producer she chose John Cale, formerly of the Velvets.

On their first night in Studio A, the band recorded a cover of Van Morrison’s stirring garage rock classic “Gloria,” which she welded to “Oath,” a poem she’d written in 1968, with the opening line: “Jesus died for somebody’s sins but not mine…” She later chose the song as the first track on Horses, “claiming the right to create, without apology, from a stance beyond gender or social definition, but not beyond the responsibility to create something of worth.”

The song would remain a peak moment in most of her concerts ever after, just as the full album of material continues to hold together as a cohesive body of work. In her recent run of Horses shows neither the songs nor Smith had lost their power.

During a November 15 tour stop at Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, Smith quickly got the crowd to its feet with “Gloria.” Standing onstage with Smith, her long thick hair now fully gray, was her band, including son Jackson Smith on bass and guitar, and Lenny Kaye, her partner on guitar ever since that first reading at St. Marks.

For “Birdland,” a song that was borne from an in-studio improvisation, Smith began by reading the opening lines from a book—“His father died … and the boy was just standing there alone”—to a gentle piano melody. As the tune smoldered with a strange soulfulness, there were delicate accents from the band, but Smith’s voice was the song’s main instrument and percussive heartbeat. She soon threw the book to the stage floor and removed her glasses to erupt for a passage describing a feeling of creative ecstasy: “I’m going up, I’m going up / Take me up, I’m going up, I’ll go up there!”

As the band began the album’s epic title piece, “Land: Horses / Land of a Thousand Dances / La Mer(de),” Kaye plucked a strange, simple rhythm on his guitar that sounded like the helicopter blades from Apocalypse Now, leading to Smith getting the crowd back on its feet to shout along to the excited, mysterious mantra-like lyric: “White shining silver studs with their nose in flames / He saw horses, horses, horses, horses, horses, horses, horses, horses!”

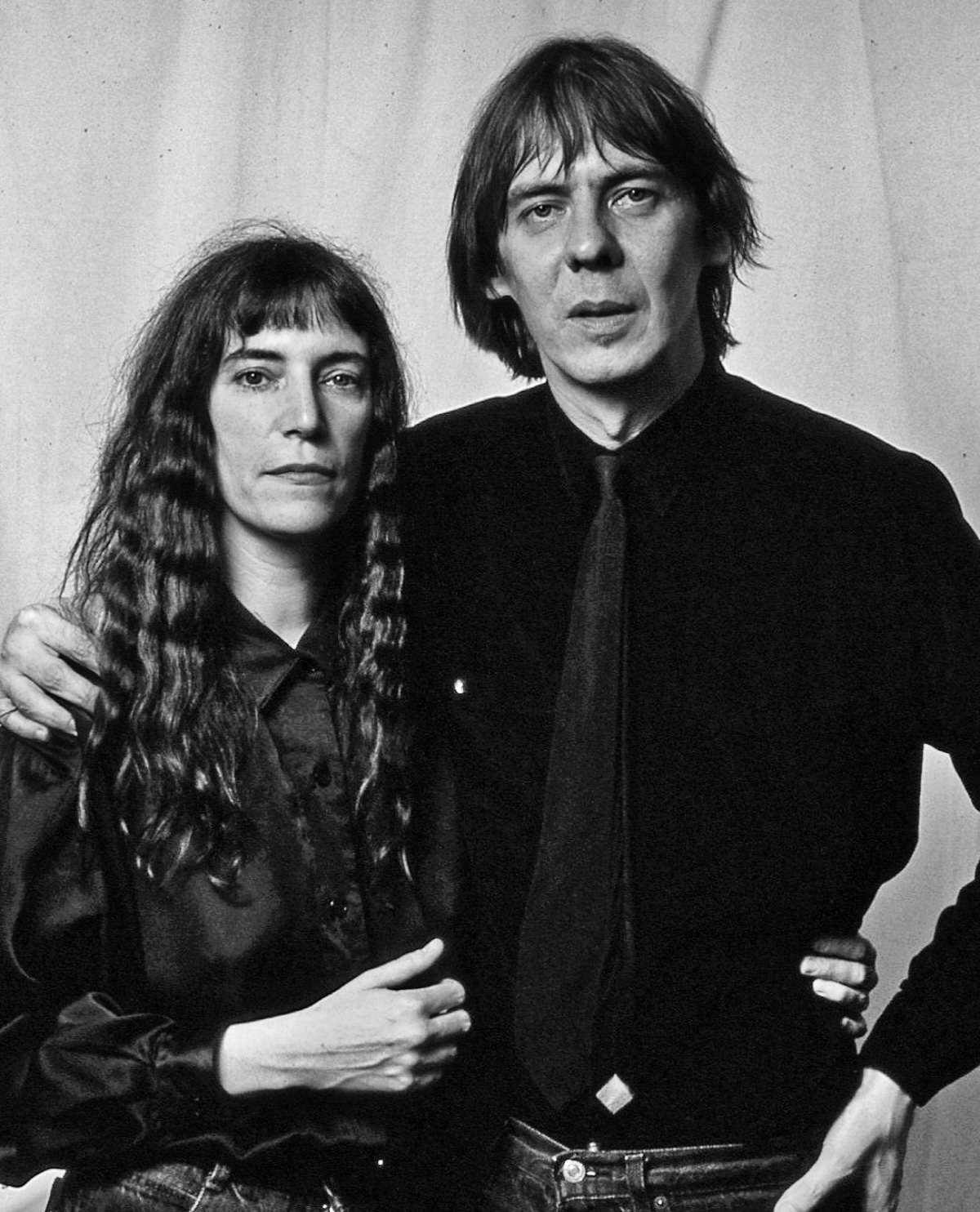

On tour for Horses in 1976, Smith attended a welcome party for her band in Detroit, where she met Fred “Sonic” Smith, formerly of the revolutionary proto-punks the MC5, and her future husband. That first meeting was brief, but soon led to a life-changing romance with a fellow rocker “whom I loved for a time more than myself,” she writes. He also inspired her poetry, plus the songs “Dancing Barefoot,” “Frederick,” and the torrid “25th Floor,” recounting their first romantic encounter in a hotel’s glass elevator soaring high above the Motor City.

Their story is at the heart of Bread of Angels, as Mapplethorpe was for Just Kids. When she retired, disappearing into marriage and the suburbs of Detroit in 1980, her departure left behind a career that seemed abbreviated, artificially cut short. But for her, “The desire for illumination eclipsed that of ambition.” She spent 16 years in Detroit, which she describes largely as a time of happiness, study, and creativity. She wrote at her kitchen table early each morning, putting in the work that would lead to the skills that made Just Kids and Bread of Angels possible.

Living in an old house with her family in St. Clair Shores, on the edge of canals, she was back to her original vocation: poet. After reading a new edition of Queer sent to her by Burroughs, as she recalls in the new memoir: “I knew then with all my being that being a writer was what I wanted more than anything.”

The domestic hiatus was only interrupted to make the album Dream of Life, with Fred playing all guitars, arranging every song, and co-producing with Jimmy Iovine. Mapplethorpe again photographed the cover. The album wasn’t as well-received by critics, but it produced a lasting anthem in “People Have the Power,” a song true both to Patti’s sensibilities and to Fred’s radical history with the MC5.

After a period of fading health, Fred “Sonic” Smith died at age 46 of heart failure in 1994. At the funeral, she dressed in the same silk black dress she wore when they met. In Bread of Angels, she expresses only love and loss, while leaving the sad details of his final years unsaid. “His decline was the tragedy of my life,” she writes, “and it profits no one to outline the private battles of a very private man.”

In just six years’ time, she had lost four of the men closest to her: keyboardist Richard Sohl (1990), Mapplethorpe (March 1989), Fred (November 1994), and her brother Todd (December 1994). Smith returned to New York City in 1996, now with two young children, son Jackson and daughter Jesse. And with the help of Dylan, Ginsberg, and Michael Stipe of R.E.M., she was soon back in circulation and onstage.

Honoring the dead has since become a core mission for Smith, not only in Just Kids and Bread of Angels, but dealing with the loss of her husband and too many from Kurt Cobain’s generation on the 1996 comeback album Gone Again. She also says goodbye to the fading Beat generation on the 1997 follow-up Peace and Noise. “You’re remembered!” she wails on the song “Memento Mori.”

Her song “Elegie,” from Horses, often becomes an improvised roll call of fallen friends and heroes, with Smith embracing the role of witness and survivor, left to tell their stories. In 2006, as CBGB’s final performer, she sang “Elegie” to both close her set and the doors of the legendary club. At times blunt and deeply felt, Bread of Angels is the latest chapter in that legacy, as Smith pushes forward as a timeless and still-blazing creative force.