Frank Ockenfels III first crossed paths with David Bowie by chance.

Ockenfels was assigned to photograph Bowie and his band Tin Machine for an early-’90s iteration of Creem magazine. It was the last of four photo sessions the band had endured that day in Los Angeles, and Ockenfels asked them to remove their shirts. Then, during a long camera exposure, he slowly swept a flashlight across their bodies, producing a shimmering, ghostlike effect in the final images.

Bowie remembered those strange pictures later, and they worked together again the following year, forging a creative alliance that stretched from 1991 and 2006. The result was some of Bowie’s most striking imagery from his later career. And you can see why Bowie was attracted to the Ockenfels aesthetic, which is typically vibrant and frayed at the edges, sometimes using multiple images, blur, and splashes of ink.

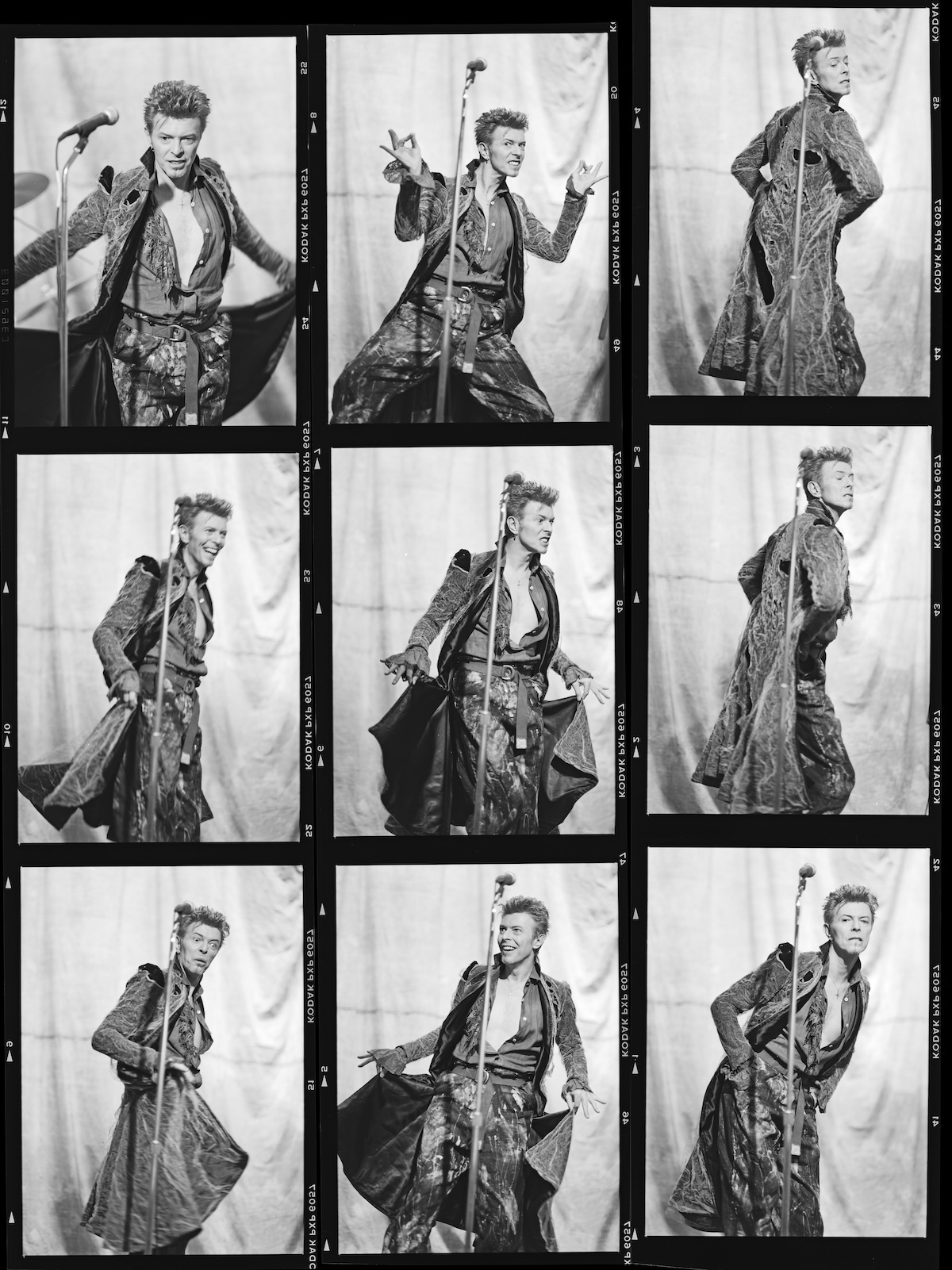

Their work together has now been collected into a book, Collaboration, credited to “Frank Ockenfels 3 X David Bowie,” gathering many portraits, candid photos, proof sheets, and drawings. “I got lucky,” Ockenfels says now of his years of work with the iconic rocker, actor, and painter. “It was a tremendous gift to me in my later 30s when I met him, kind of from the get go.”

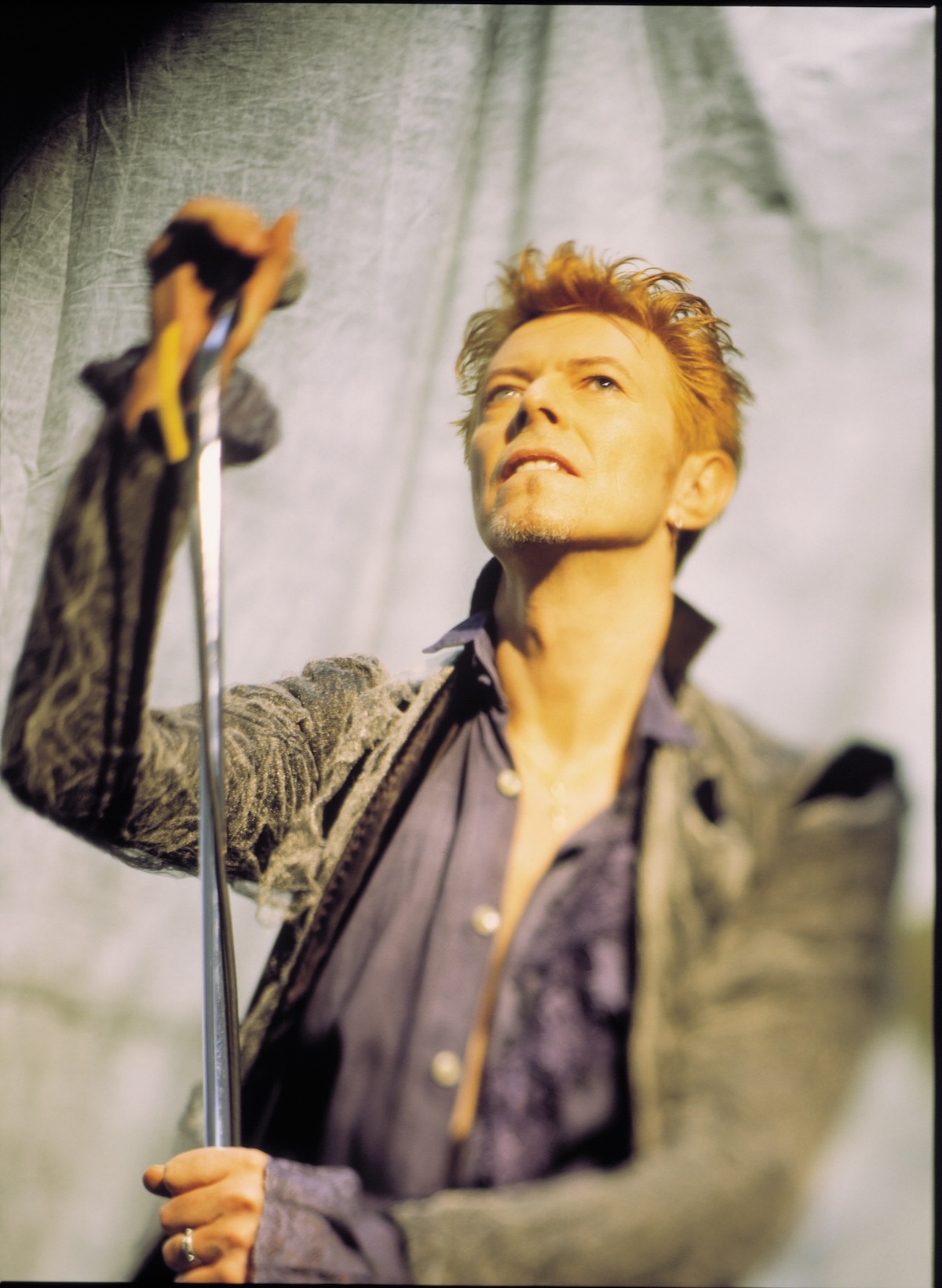

Their true collaboration clicked during their third session together, creating publicity photographs for the release of the album Outside in 1994. When it was over, Bowie invited Ockenfels to join him and his wife, the model Iman, to go see a Laurie Anderson performance, and then dinner afterwards. “I was like, ‘Is he talking to me? I’m confused,’” he recalls of the moment.

“We sat at this little square table in the back room of a restaurant and we talked about art and politics and life and things we’d seen. We discussed a lot of things. It was really lovely. It was amazing.”

Even so, he is hesitant to recall his relationship with Bowie as a deeply personal one, as some others have described it. Most important to Ockenfels is that they were collaborators, two artists who came together periodically to create some new visual totem to represent where Bowie was in that moment. “You don’t have to be friendly to collaborate with somebody,” says the photographer. “You’ve just got to be trusting and understanding of what that is. And I think David and I had that.”

By then, Ockenfels was a photographer Bowie would request or call on for his own needs. The British rock icon worked with many photographers during those years, but Ockenfels was one he kept returning to. “It was a shock to me,” he says in a video call from his studio office, dressed in white overalls over a white long-sleeved shirt, his beard mostly gray. “Every single time the phone rang and said, ‘David wants to talk to you. We have something we need to photograph,’ was always like, wow.”

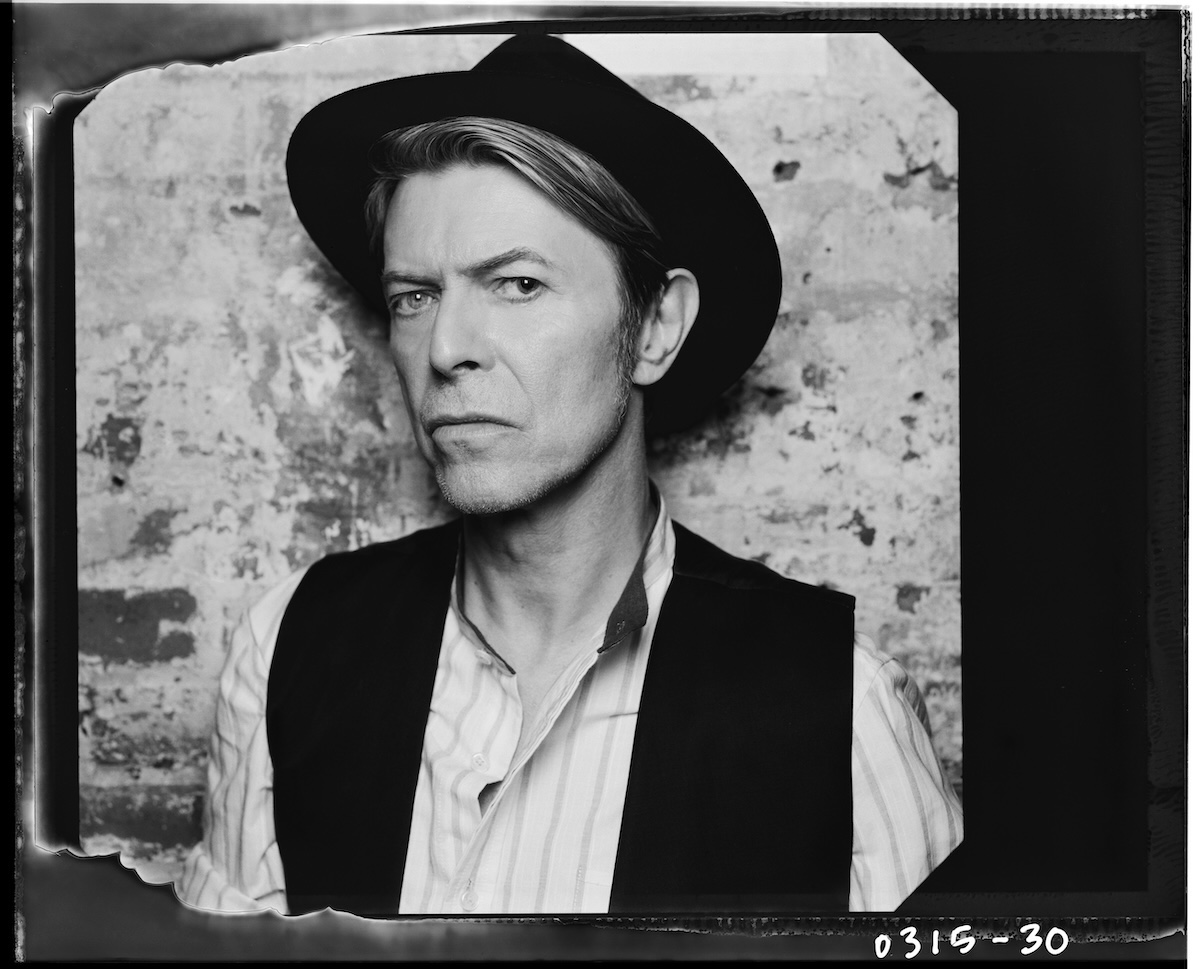

On the cover of the book is Bowie in full color, standing in front of a wall painted in deep red and smeared on the edges with black paint. He stares into the lens in a slim suit of cobalt blue, blonde hair windblown to his right. On the surface of the picture, Ockenfels has scrawled inky words written in reverse. The 2003 image is an unsteady blend of chaos and grace.

“It was the most intense day we probably ever did, and the most pictures we ever did,” he says now of the session, undertaken for the album Reality. Bowie had also been up all night in a recording studio before the shoot, maybe adding some additional edginess to the pictures.

Ockenfels, now 65, says there was simply “an ease” in their working collaboration. “I got things done quickly. I knew that we needed to take some pictures for magazines, but he always wanted to see what else I had to bring to the table, and say, ‘Okay, what do you want to do? What have you been working on?’”

Prior to meeting Bowie, the photographer was certainly aware of his music and unique presence in pop culture and the avant-garde, and enjoyed much of it, but he wasn’t a hardcore follower. That would change. And a photographer of Ockenfels’ particular aesthetic was just what Bowie needed at that time.

The repeated cliché of Bowie’s career is that it was about endless ch-ch-ch-changes—from the glitter-rock Ziggy Stardust era and his skeletal Thin White Duke period to the stylish minimalism of his time in Berlin and after—documented visually through those years from a long line of gifted photographers: Mick Rock, Brian Duffy, Helmut Newton, Anton Corbijn, and Steve Schapiro. That continued, but unlike the whiplash ’70s, when Bowie’s appearance changed dramatically, the singer cut very much the same mature figure (still youthful and trim, always impeccably dressed) during his shoots with Ockenfels. Only the haircut changed.

“It must’ve been amazing for Mick Rock back in the day to know Ziggy Stardust. The timeframe I would’ve loved to shoot David would’ve been the Thin White Duke. Something about that—the hair is slicked back and the outline of his body—was pretty amazing,” the photographer says wistfully. “Those were his characters, which he could fall into easily if you were working with him, if you asked him.”

Following the massive pop success of his Let’s Dance album in 1983, Bowie seemed to lose touch with the muse that had always fueled his work and reputation. For most of that decade, his music was largely met with disappointment from his core following, and indifference to the larger pop audience that had discovered him. His dalliance within the band Tin Machine was an attempt to reconnect to the kind of energy he once knew with the Spiders from Mars.

Bowie began to find his way again in the 1990s, even if critics were slow to come around. As always, there were many collaborators, and the often raw, impressionistic approach of Ockenfels once again provided Bowie with the visual textures of the cutting edge that once defined him.

Beginning in the late 1980s, Ockenfels was part of a movement within editorial photography that shattered the usual rules of portraiture. For him, that meant experimenting with focus, blur, graininess, with tears and scratches on the image, experiments with color and texture. Other non-conformists included the photographers Matt Mahurin, Kevin Kerslake, and Nick Night, published in the pages of magazines like Ray Gun, Rolling Stone and SPIN. Ockenfels calls it “the abstract art of creating an image that basically had the feeling of the artist.”

It wasn’t always well-received, and there were many battles with magazines, publicists, and photo editors along the way. “A lot of people didn’t go for that at all,” Ockenfels adds with a knowing smile. “Granted, most photographers are happy if they find a style and everyone buys into it. I was never that person. I was always like, okay, what’s next? What can I do differently here? How can I go beyond what was expected? The constant reinvention of yourself is the fun part of doing the arts.”

Most of Collaboration is dedicated to pictures of Bowie solo, but there are some pages given to occasional musical collaborations, starting with that Tin Machine portrait. A 1999 shoot has Bowie with the androgynous alt-rock band Placebo, one of his many direct musical descendants, for pictures to go with their torrid joint-single “Without You I’m Nothing.”

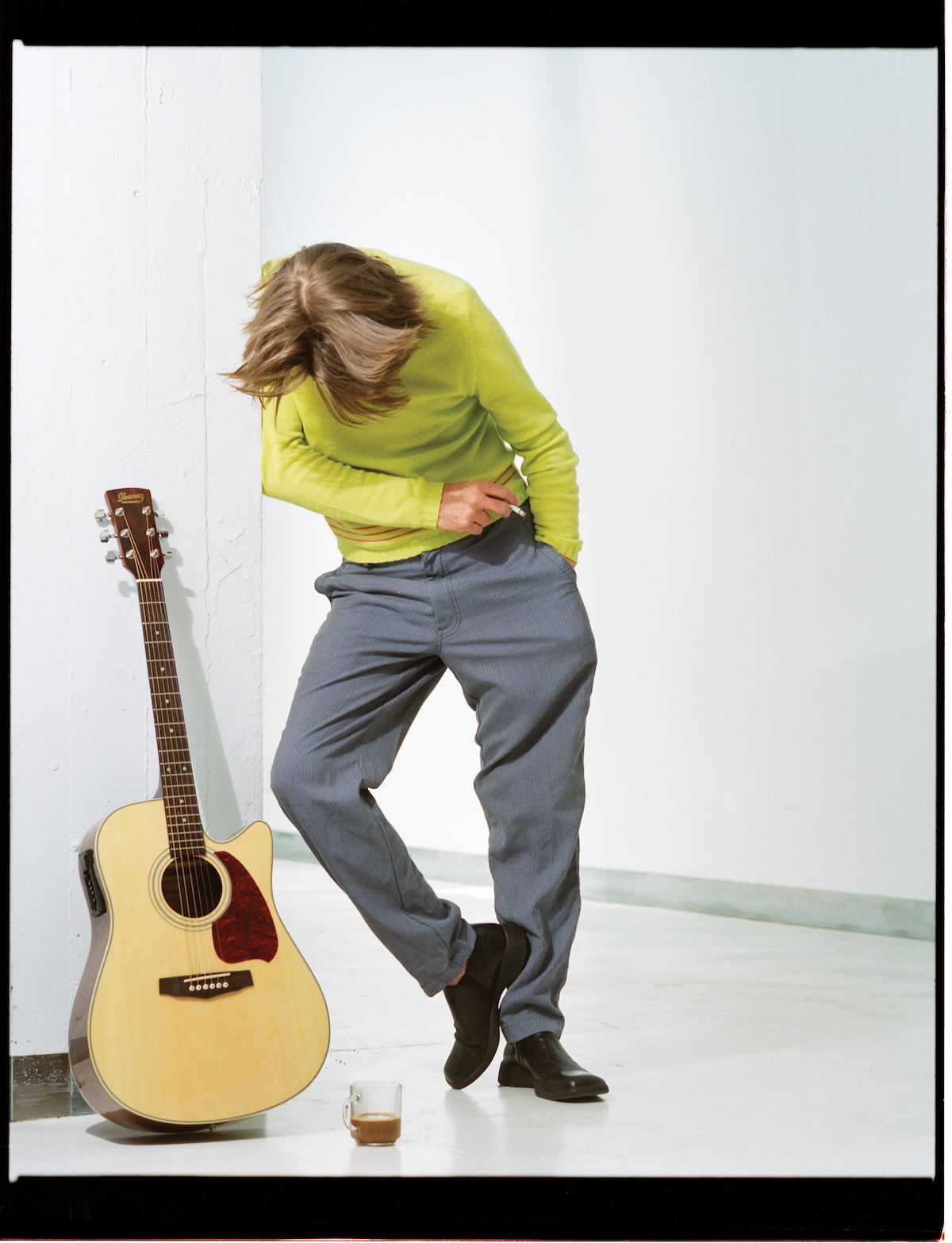

There are pictures and proof sheets from a Bowie recording session with Angelo Badalamenti for “A Foggy Day (In London Town).” The song was made for a tribute album to George and Ira Gershwin, setting the singer’s romantic vocal over the Twin Peaks composer’s haunted synth and orchestral score. It was recorded in a New York studio, and Bowie brought Ockenfels into the vocal booth with him, giving the photographer a closeup look at his creative process.

“You could see him put his little twists on things—like, ‘This is what I’m going to do here, I’m going to try it this way,’” he says. “Then he would listen, and he and Angelo would talk about what he had just done and what they wanted to do. It was fascinating.”

In 2003, Bowie showed up with a big baritone saxophone, and wore a shimmering golden suit, looking a lot like the King himself on the classic album cover of 50,000,000 Elvis Fans Can’t Be Wrong. “That was so much fun to shoot,” he remembers. “That was like me stepping backwards in his life and presenting him as if he was the Thin White Duke with a saxophone.”

They had sometimes discussed the possibility of doing a book from their pictures together. Bowie would bring it up himself. “He goes, ‘What have we done? Why don’t you show me what we have?’” recalls Ockenfels.

For years, the photographer had kept journals where he would combine pictures with scrawled writing and random ephemera in pages and pages of collages. And Collaboration began life as a hand-made collection he made for Bowie, which included printed photographs. Some of those raw original pages are included in the new book.

“I glued the pages together and put cardboard on the top and bottom and put a cover on it and when I saw David in New York, I handed it to him and go, ‘This is what the book would be.’ So he had an idea of where it was going to go.”

Bowie appreciated the photographer’s impulse for experimentation. In return, the rocker was an especially intriguing subject—among the staggering range of iconic creators of music and film he’s photographed during his career. Another was filmmaker-painter David Lynch, who appeared on the cover of his first book, 2019’s Volume 3, and was similarly suited to the photographer’s boundary-shattering approach. Ockenfels shot Lynch three times over the years.

Ockenfels recalls of Lynch, “I made him laugh twice. He kind of thought my approach was funny: ‘Okay, I threw the barricades in front of you. Now let’s see what you do, kid. Do you fail? Do you fall at my feet? Or do you achieve something that I’m not expecting?’ And that was around the same time I was working with David [Bowie]. It was totally the catalyst of working with David, and it definitely drove other photo shoots of how I would approach people, especially people at the level of Bowie/Lynch.

“Lynch is a director. David’s a musician. Both go beyond that. They both become spiritual and artists that are very aware of the world and have conversations. Those people are always tougher.”

As his career evolved, Ockenfels became an in-demand photographer for movie posters and other promotional images, and he worked regularly with major filmmakers and actors. “I was just on a movie with Ray Fiennes and to basically stand and look him in the face and talk to him is totally tough,” he says with a laugh. “I mean, it’s not easy. He’s very intense and he looks right at you, but you have to be aware of what to do with it.”

With Bowie, the creative conversation lasted more than a decade, but came to a close not long after he began having health issues, and he stepped away from the spotlight for a time. After suffering two heart attacks while touring Europe in 2004, Bowie retired from the road and released no new albums for several years.

In the book are a few images from the final shoot Ockenfels did with Bowie in 2006, in Manhattan for the cover of Q magazine’s 20th anniversary issue. “He asked me if I’d come to New York to do it for him,” Ockenfels recalls. Bowie wanted a simple portrait, and that’s all they shot. “He still said to me, ‘We need to do one last shoot for the book, whenever you figure it out.’ And then I didn’t hear from him.”

Bowie didn’t release another album until 2013 with The Next Day. Then came Blackstar three years later, a startling, jazz-imbued meditation on mortality released to great acclaim just days before his death from cancer.

“Someone said to me, ‘Did you ever feel like you missed out on something with David?’ And I’m like, yeah, that was it—to not be on Blackstar, to support him through that … I would’ve loved to have been the photographer to do that with him,” Ockenfels reflects. “It might’ve also broken my heart to see him like that, because he was always so vibrant when I was around him.”

A lasting echo of that energy is preserved within Collaboration. Ockenfels has experienced many memorable sessions in his career, including with Bruce Springsteen, Sting, Garbage, R.E.M., comics and bombshells, movie villains and superheroes, Jack Nicholson and Breaking Bad, and Timothée Chalamet as Bob Dylan. Bowie still stands out.

“David is definitive in that. There’s nothing else that’s really happened to me in my life that would be so worldwide,” Ockenfels says with a smile. “I did three Harry Potter movie posters, and I did Superman this year. But that doesn’t get you the same thing as saying, ‘Well, then I shot David Bowie.’”