In the life and work of artist Shepard Fairey, social justice and the musical counterculture have always collided, igniting many of his most striking images.

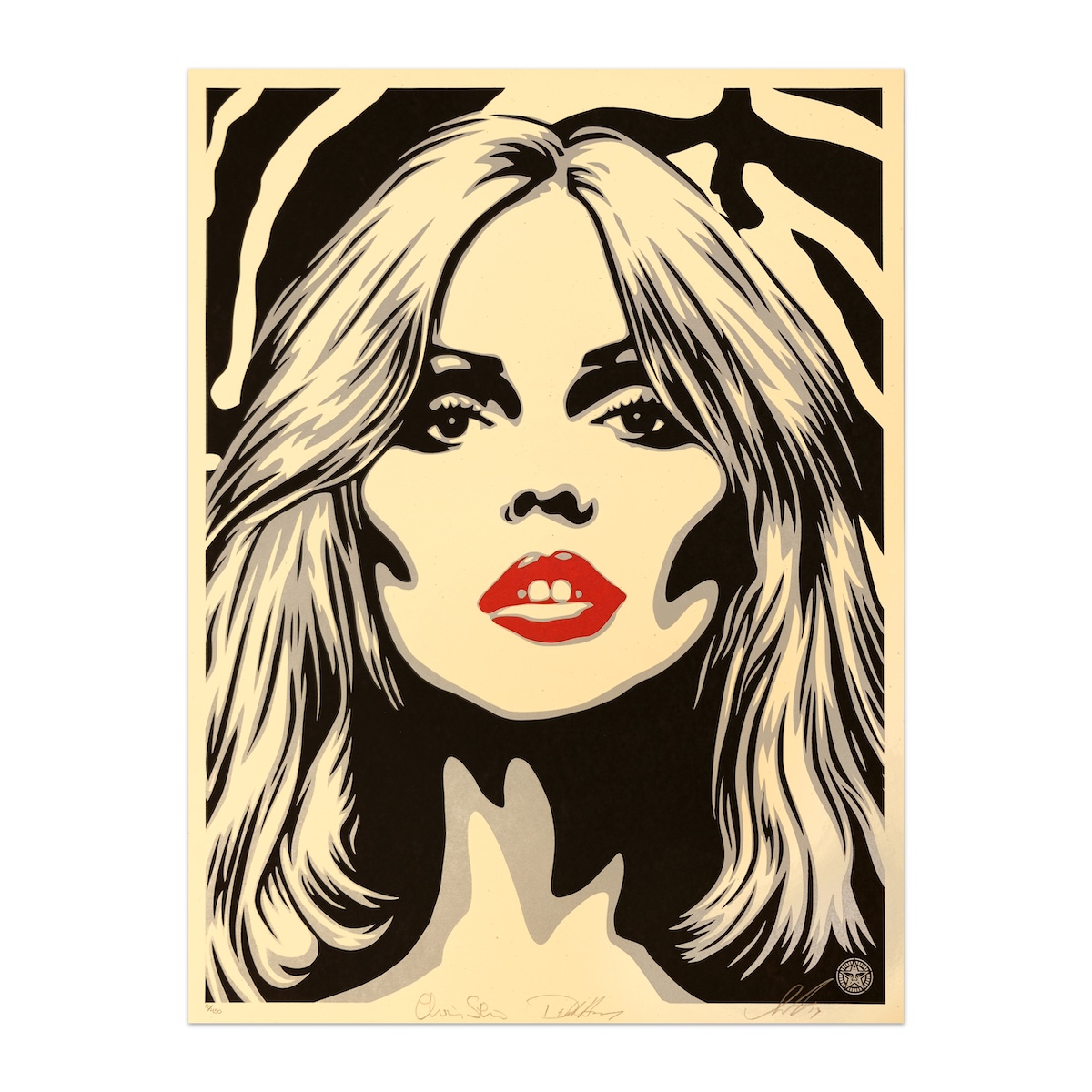

Most famously, they have come in the form of 18-by-24-inch posters, with messages against police violence, war, and government surveillance, and calling for peace, civil rights, and multiculturalism. There are also many portraits of Fairey’s cultural heroes, among them Bob Marley, the Sex Pistols, Public Enemy, Black Flag, Andy Warhol, the Clash, Keith Haring, David Lynch, and Black Sabbath.

An exhibition of that work, Shepard Fairey: Out of Print, now at the Beyond the Streets gallery in Los Angeles, brings a vast selection of these now-rare posters back into public view. While Fairey long ago graduated to painting huge murals in his distinctive graphic style on the sides of buildings, the posters and the urgency of street art remain at the heart of his work.

“Anybody that sees this show will see that there are consistencies for 30 years, but there’s also a lot of evolution,” says Shepard, who describes his core issues as “racism, sexism, xenophobia, abuse of power, greed.”

“There’s a celebration of heroes, but there’s also condemnation of villains like Bush or Nixon or Stalin or Mao, and they’re all in there,” he adds, noting that some viewers can be confused by his depictions of political leaders, like Saddam Hussein, as if he was celebrating them. “It’s like, be careful who you put on a pedestal.”

With 421 pieces, dating from the mid-’90s to the present, it is the largest showing of his prints that Fairey has ever done in the U.S. The images tend to be high-contrast and minimal, with shades of red, blue, and gold, rooted in crisp graphic design and the visuals of Soviet-era agitprop.

The prints have the energy of activism and the spirit of various cultural archetypes and narratives where those overlap. One wall at the gallery is filled with a grid of faces that includes Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Motörhead’s Lemmy Kilmister, civil rights icon John Lewis, and Nirvana’s Kurt Cobain.

“I’ve taken that spirit of punk rock, that willingness to speak out, to not worry about whether you’re out of step with mainstream tastes and opinions, and I’ve tried to apply that in a bit of a more constructive way,” Fairey says. “I love NWA. I don’t love the misogyny, but I love that they’re just gloriously not giving a shit.”

While Fairey has his own gallery in Los Angeles, called Subliminal Projects, it is smaller and he has another upcoming show planned of his fine art there. So he turned to Beyond the Streets, the gallery founded by Roger Gastman to celebrate street art and other forms of urban culture.

Fairey has known Gastman since 1998, and together they published Swindle, a magazine on art, lifestyle, politics, and fashion, for more than four years. On the magazine’s covers, they put some of the same cultural heroes that Fairey has often depicted in his work.

Across town in L.A., where Fairey is based, are three unfinished luxury towers, abandoned by Chinese developers, that have been taken over by graffiti artists, leaving their marks inside and out. The giant buildings have now stood there for years as a monument to out-of-control development on streets populated by the homeless and have become a canvas for any artist willing to climb 52 floors.

“Graffiti is very alive and well in L.A., not just on those abandoned towers, but everywhere,” says Fairey, 55. “That always makes me feel hopeful for what younger people are doing, how they are going to express themselves, whether it’s legal or not, and say, I exist. Like, ‘You don’t want me to exist, but fuck you, I exist.’”

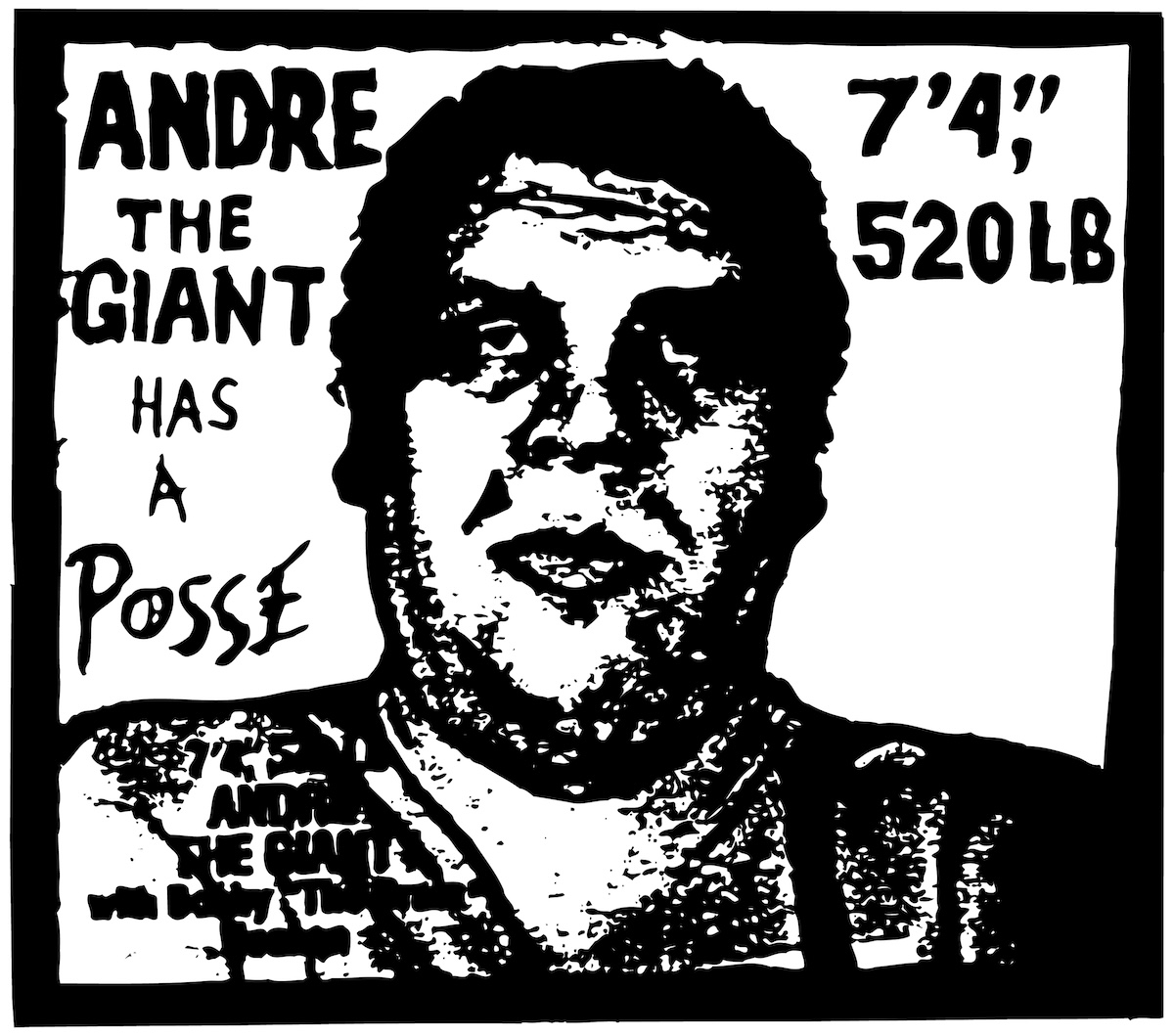

While a student at Rhode Island School of Design in 1989, he began his “Andre the Giant Has a Posse” sticker campaign, which evolved into his larger Obey Giant guerrilla‑style street art project, and a large selection of those posters are included in Out of Print. The exhibit also displays the tools of his trade: brushes, X-acto knives, ink, cans of paint, stencils, rubylith masking film, wallpaper adhesive, pay stubs, worn-out sneakers, and “all the stuff that demonstrates to people the sort of DIY methodology that’s the underpinning of everything I do,” he says.

Against one wall in the gallery is a display of multiple vintage TVs, with flickering clips of the show’s subject matter, documentary footage of Fairey in action, and live shots of visitors from surveillance cameras.

One poster on display is for his band Nøise, an electronic-alternative quartet that released an EP in 2016, sharing wall space given to the artist’s punk rock obsessions: the Ramones, Bad Brains, Keith Morris, Misfits, OFF!, Henry Rollins, and more. On December 16, Fairey will appear for a 7:00 p.m. conversation with Circle Jerks founders Morris and Greg Hetson.

“I admire Henry Rollins. I admire Steve Jones. I admire Chuck D. I admire the guys from Rage Against the Machine. And I’ve ended up being able to work with a lot of them. And of course, it’s very validating,” Fairey says.

“What I also realized is that the tendency for a lot of people—including maybe me when I was younger—was to think, ‘Oh, these people are doing this thing. They get a lot of adulation. They got it handled.’ But relative to the size of the population, it’s a really small number of people that live what those people put into the world. … So I am now working with a lot of them knowing the realities of it. I feel that much more motivated to enroll people to actually just get involved and get off the couch.”

One musical figure who towers above the rest for him was Joe Strummer of the Clash, represented at the gallery show on multiple posters. “Strummer’s my biggest hero ever,” Fairey says of the revolutionary rocker, whose first-wave U.K. punk band was labeled “the only band that matters.”

The artist communicated with Strummer from a distance, and then missed out on what turned out to be his one chance to meet the musician before his death in 2002. Strummer was in L.A. visiting his label, Epitaph Records. “I was invited to go down to Epitaph to hang out with him one day. I had some dumb corporate project due that day,” he recalls. “He died six months later, and I never got to hang out with him. One of my biggest regrets in my whole life was I didn’t say, ‘I’ll miss this deadline on this project and go hang out with Joe Strummer.’”

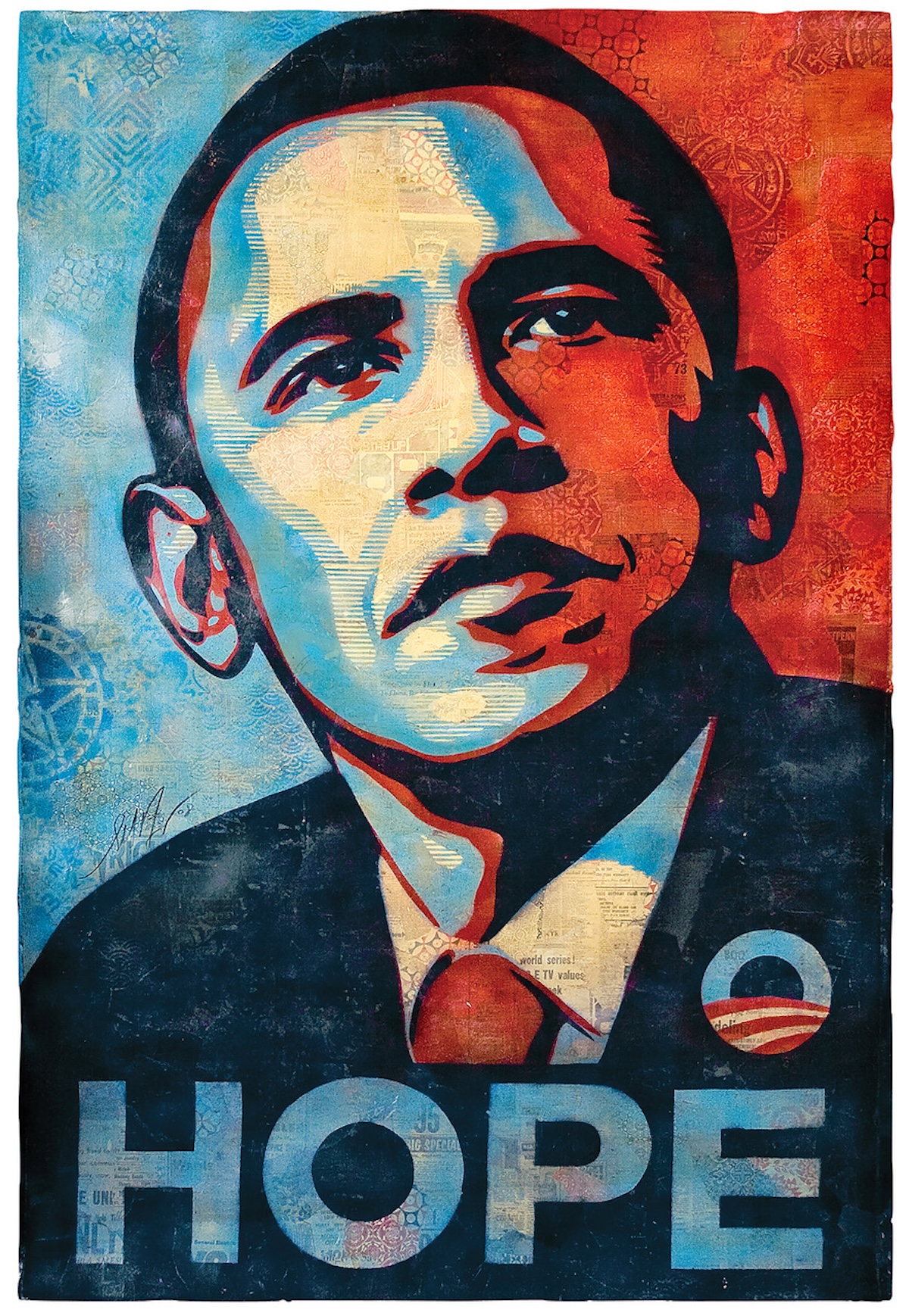

Fairey’s own notoriety soared in 2008 with his creation of the “Hope” poster for Barack Obama’s campaign for president, which now hangs at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C.

“There’s pros and cons to being known. Familiarity breeds contempt,” Fairey says. “Any mid-career artist is going to not be the hot new cause to celebrate. But I think where I’m able to make up for that is that my spirit is just as defiant and punk as it was when I was 25 or 15. It might not be packaged in exactly the same way. But I also am happy that I have a broader audience.

“A frustration I had when I was younger was that I felt like I was only connecting with people who agreed with me, who would say, yeah, everything sucks and give me a pat on the back, but then refuse to engage with the broader culture or the dominant system in a way that would change it for the better.”

While Fairey did create a similar poster in support of Kamala Harris in 2024, he’s largely avoided depicting Donald Trump in his work. But one poster from Trump’s first term is included in his L.A. show—a collaboration with the band Franz Ferdinand, which is just a closeup of Trump’s snarling mouth beneath the word “Demogogue.”

“I generally don’t want to do anything of Trump because he’s like a negative energy organism that just grows and mutates and spits off a new spore when he gets to claim he has been persecuted,” Fairey says. “I think that it’s better to not even address him. I say he’s the zit, and I’d rather address the underlying bacteria.”

Fairey has just released a new poster called “Fall of Freedom,” which depicts a handcuffed Statue of Liberty holding her hands to her face in despair beneath the words, “It can’t happen here.” The poster release is part of a national pro-Democracy initiative from the arts community that also includes the artists Robert Longo and Dread Scott.

“There needs to be a popular uprising in the way that on the right there’s been this populist support for oppression,” Fairey argues. “There needs to be something not just equal and opposite, but superior and opposite from the progressive side of things. I think little statements from street art make people feel like, ‘Okay, someone else is saying it. I can safely say it too.’