Sometimes even Mike Dirnt must escape from loud noises. The Green Day bassist and founding member has just been running around his Bay Area house shutting windows and doors, after gardeners unexpectedly turned up the blowers just when Dirnt was about to jump on the phone. “It was dead silent here until about five minutes ago,” he says with a laugh. “It sounded like they were cutting trees down everywhere.”

Minor interruptions aside, the last two years have been spectacular for Green Day, starting with the release of Saviors in January 2024, debuting at No. 4 in the U.S. It was followed by a tour that had the pop-punk hitmakers—also including singer-guitarist Billie Joe Armstrong and drummer Tré Cool—headlining stadiums and festivals around the world.

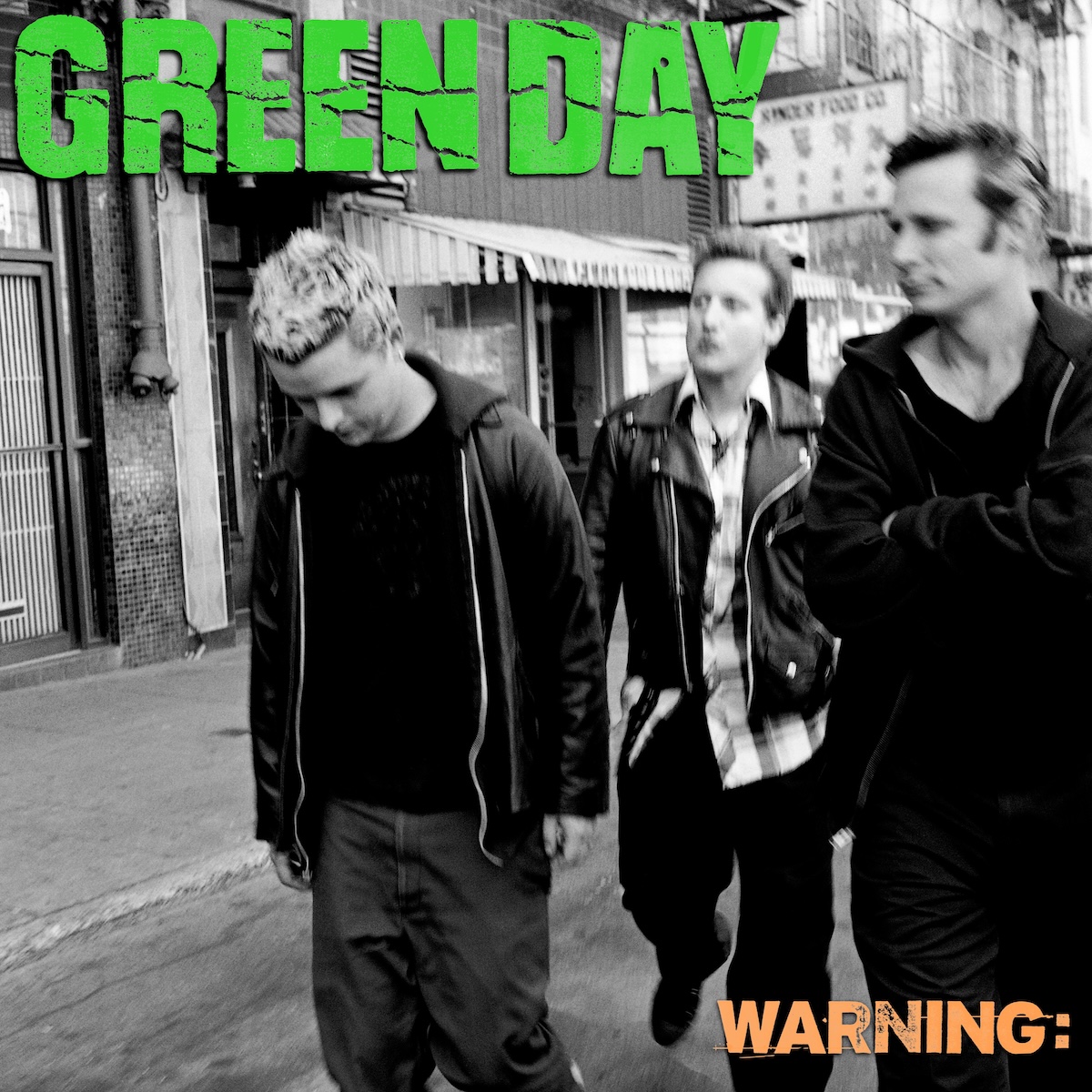

The band’s fourteenth studio album, including fan-favorites “The American Dream Is Killing Me” and “Bobby Sox,” was reissued in an expanded edition in May as Saviors (édition de luxe). On November 14, the band also released a 25th anniversary of 2000’s Warning, a commercial disappointment at the time following the double-platinum Nimrod, but for fans it’s become an essential part of the band’s musical history. Dirnt also has a new signature bass, the Epiphone Grabber G-3 bass, that replicates the instrument that he played at more than 700 shows, and which he hopes will help inspire a new generation of musicians.

Now nearly four decades since the band’s early days playing at Oakland’s 924 Gilman Street club, Dirnt spoke with SPIN about his past and ongoing present with the punk/alternative rock act.

The year 1994 was a big one for Green Day, with the release of Dookie, multiple hits on the radio and MTV, a mud fight at Woodstock, and then the traveling Lollapalooza tour. How do you look back at that time now?

That was kind of the fuse, right? Woodstock and everything just sort of exploded after that. It was crazy. I wish at the time I would’ve taken a little more time to be in the moment. But how can you, you know? Things are so chaotic, so fun. We had something to prove back then. We were opening Lollapalooza, and we wanted to come out and basically show people what we can do.

By the time Lollapalooza actually happened, Green Day were already exploding, so being the opener was a weird position to be in.

Well, that was the thing. There was a little pressure because we had sold a lot of records. By the time we hit Lollapalooza, we had sold close to as many records as anyone else on [the bill]. You’re like, “Let’s see if we can’t make a splash.” That’s a good kind of humbling. [laughs]

When that happened, you went from being a punk band known to a particular musical community and became a group known to all kinds of people. Did that change how you saw what you did and what the possibilities were?

Me, Billie, and Tré basically just said, “It’s this or nothing.” We were getting too big for small clubs anyway. The shows were getting shut down at small clubs, and it was definitely sad a little bit because we were leaving some of our past behind, but we were moving into the mainstream. It was exciting too. I mean, at Lollapalooza, the Beastie Boys were so good on that tour. I remember just going, “Man, they’re just slaying it,” because they were doing all the instruments and rapping, and they were at a really hot point. And then also seeing Smashing Pumpkins, which to me are so musical and they sound so good. So it was like, okay, now we’ve got to focus our sights on getting there.

You recently talked about how you were also playing jazz at around the time of Dookie.

I always say my bass is like this really great roommate that doesn’t judge me. He is there when I need him—or her. It’s been an emotional outlet, but I’m not being guilted if I’m not, like, practicing scales. Back then, I was playing with a few friends that were really into jazz as well, and one of them gave me the Real Book [of jazz standards], and I started picking out the main keys and writing my own lines around whatever song they were playing, because I can’t read music. I’d write my own lines and sit in with them for eight or 10 songs.

What do you think that added to what you were doing as a musician?

It’s like a secret sauce for Green Day. Billie grew up singing standard tunes, and Tré started off playing jazz drums. That’s a great keystone for any good drummer. He plays great jazz. In fact, on this tour, he jumped in with a bunch of people at random spots and he just was killing it. That swing and that shuffle is something that we dip into a lot that other bands don’t always get to. I don’t have the dexterity of a lot of amazing bass players, but I do have a pretty good ear, and I hear melodies like crazy.

When Saviors was about to come out, you played it in full at the House of Blues in Anaheim, California, and the new songs were pretty immediate. Could you tell early on that it was a special record?

In the latter part of 2022, there were discussions about us touring in ’23. Billie and I were talking, and I said, “I feel like we’ve got about six really good songs right now, and I’d rather not be rushed. I feel like we’re onto something.” He said that’s exactly what he was thinking. I said, “A great album lasts forever, a great tour lasts a summer.” Billie said, “I want to write an essential record, essential to our catalog.” And that was it—the decision to go after it. And I think we did. I can snap a line from songs on Saviors to every one of our records: “Oh, that’s reminiscent of Kerplunk, that’s reminiscent of Nimrod, that’s reminiscent of Warning.” I could see the culmination of it all, but somehow it has this cohesive nature that is very present Green Day.

A lot of that has to do with the three of us, the way we’re playing off of each other. We got in a room and we really played these songs together. People say, “Oh, so what that you got in a room together?” It’s actually a thing though, because I’m hearing how hard Tré is hitting this snare, how hard he’s hitting that kick drum. You’re also in the room with each other’s emotions, and you can feel that too.

Was there a particular song during the making of that album where you felt like the band had tapped into something?

One of the first songs Billie wrote was “Saviors,” and that song felt like a mission statement. It was a wide palette we could go off of. And then there was stuff like “One Eyed Bastard”— it turns out James Gandolfini’s favorite record was Dookie. We got word back from Michael Imperioli of “The Sopranos” that [Gandolfini] would go back to his trailer and listen to Dookie on vinyl. Billie was getting a kick out of that, so he started writing this song that had this gangster overtone, the “Bada-bing, bada-bing, boom!” And I wrote this little Irish thing in the middle of the chorus, so it turned into a Gangs of New York thing, and you could hear all the different things firing. That’s when it’s really good. Tré’s doing really good drum work where he is making the song more dynamic and musical, and Billie’s got a great melody going, and I’m able to pepper in this other hook that was unexpected. We’re always going for that, but sometimes it really, really works. [laughs]

Green Day also put out this year the 25th anniversary of Warning. At the time, it was seen as a commercial disappointment. How do you feel about that record now?

I’ve always loved that record. That was a time where we wanted to expand musically and try new things, and we had come off of trying to do that with some songs on Nimrod, but this was just different. Billie was listening to a lot of different folk-type music and we wanted to lean in on that. It was certainly when Billie lyrically was digging into more social-political issues, and it was a turning point for us. Without that record, there’s probably no American Idiot.

That same year you guys played the Warped Tour, and because the album didn’t explode as before, it seemed like you were in a rebuilding period.

You’re not wrong. You can still believe in what you’re doing, but if people don’t get it, it lights a good fire, and I think that [happened] for us. We were watching other bands come up and get really popular that we felt were very similar [to Green Day]. In the long haul, it was really good for Green Day too. But at the time, it’s a pill to swallow.

Even for a band that’s had great success, there can be dramatic ups and downs during that early period. But Green Day persevered and today you’re playing stadiums.

I remember playing some shows in Europe and the arena’s half full, and that was tough. In Europe, house music was really kicking in everywhere, and there was just a real change that was going on in the world. All we could do is be the best Green Day we could do, and try and keep growing. We always wanted to be a band with a career arc, and we always wanted to push forward. It’s our job to create.

On the expanded Warning is the song “Scumbag,” which you wrote.

I had a falling out with a friend, and I over time realized he was a very toxic person. He’d come around and every time he did, there was something sort of charismatic about the person, but there’s also something super full of shit. [laughs]

Is “scumbag” one of your go-to words for that situation?

I think it’s a little classier than douchebag. [laughs]

Green Day has been playing stadiums, but playing smaller rooms still seems to appeal to the band.

It’s important to mix it up. One of my favorite shows of this whole thing was when we were in London, we decided day-of to play The Marquis bar, and it sits maybe 80 people. People were standing on the bar and everything. It’s a well-known bar and we played an acoustic set there. But there’s 650 people outside the club, outside the window, singing. It was epic. And I love those moments. I live for that stuff. The small club stuff and theater shows, it feels so intimate. There’s this sweet spot like the Bowery Ballroom—there’s an intimacy, but it also feels kind of big.

How did you end up playing music?

When we were really young, Billie showed me his guitar, and he tried to show me a couple chords, and I didn’t get it. I’d never held a guitar before. And then my mom’s roommate had a guitar, and this guy Pete started showing me chords. And one night me and Billie had a sleepover at his house, and I go, “You know I play guitar now, right?” He’s like, “What? You wanna learn a couple songs?” I sat on one bed, he sat on the other, facing each other. And we ended up figuring out “Crazy Train,” “Ain’t Talkin’ ’bout Love,” and “Photograph.” That was it for a bunch of sixth graders. [laughs]

And choosing the bass?

I was 14 years old. We were having band practice, and our bass player had a dentist appointment. I looked at his bass and Billie goes, “You have to pick it up.” So I picked it up and we jammed through a couple tunes, and I was like, “Oh, man, here we go. I think I just turned into a bass player.” [laughs] It was like, this feels great. And I can be a little more muscular and dig into it.

In those early days of Green Day, did punk rock become a mission for you?

I had a cassette player early on. We started going to Gilman and a friend of ours, whose name is Eggplant, he gave me a copy of this thing called East Bay Sampler and it had all these really great East Bay bands. The bass player roster in the Bay Area was really deep. These guys were awesome and melodic. No matter what type of music they were playing, they were fully committed to the melody. So [Green Day] were almost immediately going for songwriting.

How much did Green Day have to go through criticisms from punk rock gatekeepers when you started getting actually popular?

We sort of went through it earlier. [laughs] We could not get a gig at Gilman Street to save our life until John Kiffmeyer, the drummer on our first record, joined the band. Everyone was just like, “You’re too poppy.” I’m like, “Yeah, we’re fucking 14, 15 years old. We’re singing about girls. What else do we know?” [laughs] So we kind of dealt with that, where it was never fully embraced by the community. I love that community, but we were garnering fans and people liked what we were doing, so we just played to those people. At the end of the day, our melodies will speak loud and we’ll evolve as a band.

There is a history of punk rock musicians getting official signature instruments—Billie Joe Armstrong, Johnny Ramone, Joe Strummer. When did you first get yours?

Oh, my gosh. I think it was right around American Idiot. I didn’t even know that was a thing until we were well into fame. [laughs] I worked with Fender. I always really loved the Tele body shape. I put a lot of work into it. It’s about creating great instruments—same as a record: Let’s create something great that lasts longer than we do. I just give basses away like lollipops. The other side of it is just inspiring people to pick up an instrument. I remember in school, they just didn’t have any instruments. It took me a year to get 13 basses to the Los Angeles Unified School District to their music program. So sometimes I just buy them and give them out myself.

The [Epiphone] G-3 is sort of shaped like my Millennium Falcon. [laughs] I have the Star Wars birthday [May 4, as in “May the Fourth Be With You”]. I’m a Star Wars kid. My [old] G-3, I played 700-something shows on my bass years ago. You look up any old pictures of me traveling the world, it’s always that bass. It was such a huge part of my sound and look when I was younger. It’s just bigger. I can’t wait to see really small people—like small girls or really skinny little guys—playing this because that’s how I was when I was a kid. You’re playing this monstrous bass. The smaller you are, the cooler it looks.