Twelve-year-old bass virtuoso Ellen Alaverdyan (better known as @ellenplaysbass on Instagram and YouTube) looks nervous as she waits for one of her idols—acclaimed bassist, singer, and songwriter Bootsy Collins—to appear on screen. She occasionally sweeps her long, brown hair out of her eyes, smiling shyly, as her dad, Hovak, an accomplished musician himself, comes into view to adjust the sound on her computer. Behind her, hanging from the wall, is a stellar collection of electric guitars and basses, along with a few amps and a white Yamaha drum kit placed strategically on the floor.

Alaverdyan was 8 years old when she was inspired to play bass by watching Australian bassist, singer, and songwriter Tal Wilkenfeld perform on TV. While Hovak taught her the basics of the instrument, Alaverdyan learned much of what she knows (which is a lot) by watching YouTube videos and using the instrument tutorial website and app Yousician.

More from Spin:

- Release Roundup: Mariah Carey, Nick Drake, My Chemical Romance

- Jordan Firstman Has Some ‘Secrets’ He Wants to Share

- 5 Albums I Can’t Live Without: Dan Wilson of Semisonic

She began posting herself playing bass online and has garnered a following of hundreds of thousands of fans, including legendary guitarist Steve Vai, with whom she accompanied onstage.

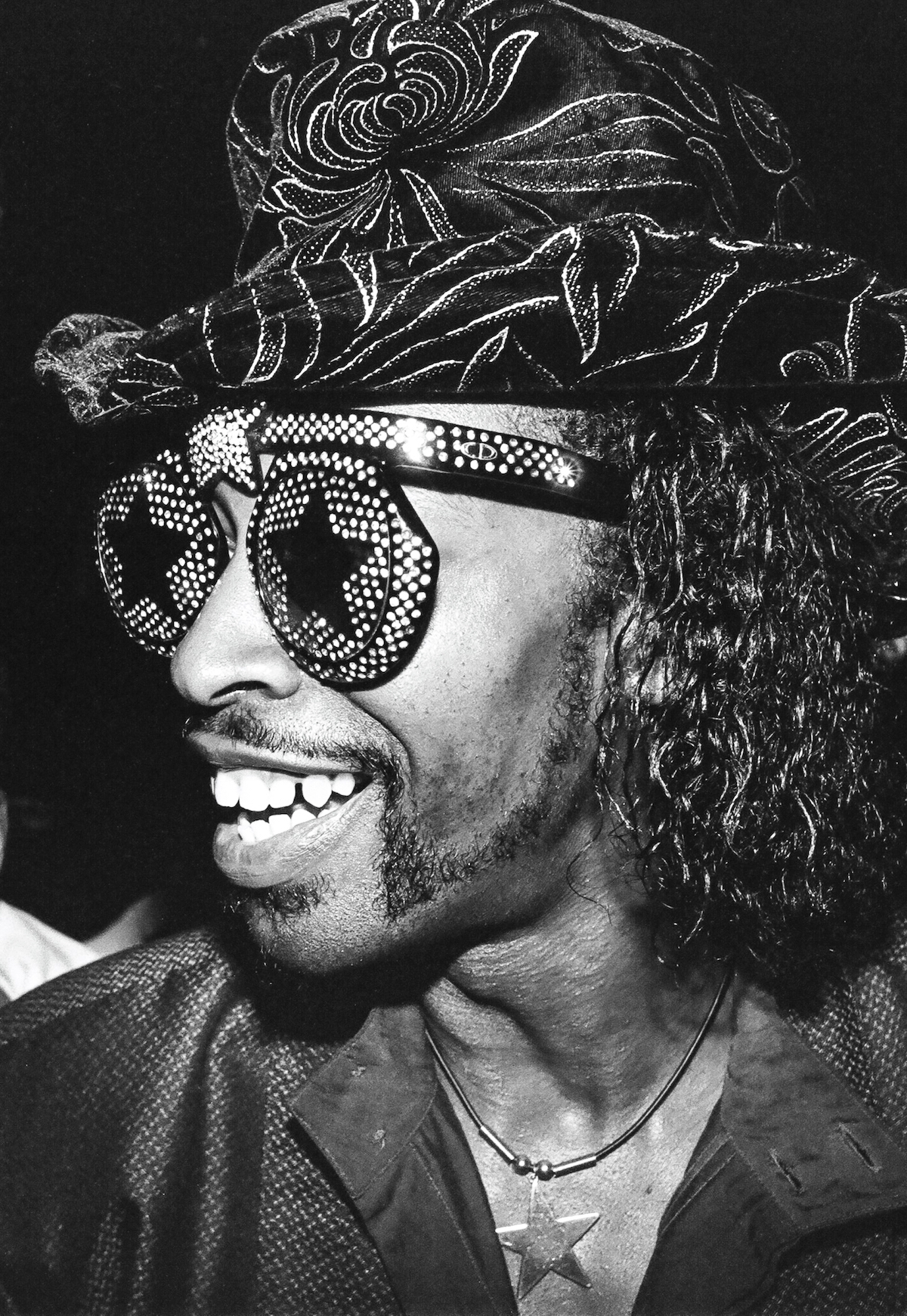

Collins comes on screen adorned in his signature star sunglasses and top hat (both in black and white), and says, “We are ready to go.” Alaverdyan’s face lights up with a huge smile as she throws her arms open wide and says, “Okay!”

Exclusively for SPIN, the funk legend and the 12-year-old bass prodigy discuss how Collins got into music, his most embarrassing moment, and his 23rd studio album, Album of the Year #1 Funkateer, out April 11.

Bootsy Collins: How you doing, Ellen?

Ellen Alaverdyan: Hello. How are you?

BC: Good. Just working in the studio and trying to finish these records.

EA: So at what age did you actually start playing the bass?

BC: Well actually, I started playing guitar when I was 9 years old. And it was because of my brother. He played guitar and I wanted to be like him. I was stealing my brother’s guitar when he went on his paper route. So, you know, practicing and playing whatever I heard on the radio and trying to learn. I wasn’t thinking about playing bass because I was trying to be like my brother and he played guitar. So, it kind of led over to playing bass.

EA: What is your favorite hobby besides music?

BC: I used to be really good at riding motorcycles until I took it too far and crashed. That used to be my favorite thing, was riding motorcycles and going fishing out on the ocean in Florida.

EA: How did the crash happen?

BC: I was just doing stupid stuff. I just got to a point in my career where I started feeling invincible and I wanted to try different things because all I was into was bass playing and then performing.

EA: What were your biggest musical influences growing up?

BC: I would have to say it started with my brother, Catfish Collins. And it went to Lonnie Mack. I don’t know if you ever heard of him. He was a great guitarist—blues and country. And every guitar player wanted to learn his song “Memphis”—and all those songs that he used to play. Because instrumentals were hot back in the day, not like today. Musicians wanted to hear musicians, and Lonnie Mack’s instrumentals were always fire. So, I always wanted to learn how to play his songs. And that was pretty much the spark of my guitar playing. But when it led over to bass, James Jamerson was the cat. Everybody wanted to be able to play those James Jamerson bass lines that he did on Motown’s records. And then after that, I think Larry Graham was the next one to come in that changed the whole bass arena with his plucking style, the slapping, and all of that. I think he’s the godfather of that.

EA: How long did you play with James Jamerson?

BC: Well actually, I didn’t get a chance to even meet James Jamerson.He was my hero, but I never got a chance to meet him before they [Motown] moved out to L.A. They moved the whole company out there. And when I started playing with George [Clinton], I didn’t get a chance to meet him because he was always recording and I was always recording. So we never got a chance to hook up, you know? But the word was around. He knew that I loved his playing.

EA: What is your least favorite part about being a musician?

BC: I guess my least favorite would be, for sure, taking care of business. I hate that. The only taking care of business I loved was playing with the band. That was my childhood dream, to play with my brother. And we had a band. That, to me, was the most exciting thing in the world. But when I had to take care of business, that always destroyed my blessing of playing music. I had to also be the boss. And I didn’t go out there to be the boss. I went out there to play music and have fun like everybody else. But when I found out that, dang, you got to do this, you got to make sure the trucks are there, you got to make sure the bus is there. All of that stuff just messed it up for me, you know? And I think a lot of musicians feel the same way. Today they know more about the business than we did. We didn’t know nothing about the business. Nowadays, you can pick up your phone and learn all you need to know. But we didn’t know nothing. And everybody knew it, so they misused us a lot. But for me, that was alright. because if I made it through, I was cool with it. But that’s the part that I hate, is taking care of business, even though it needs to be taken care of. I just wasn’t good at it.

EA: You said you had a lot of musical influences growing up. So what was the best piece of advice you’ve ever received?

BC: It would have to be when James Brown told me about playing “on the one” [emphasizing the first beat of every measure]. That was probably the most important information I could ever get at a time when music was changing. And bass players were few, not like today. Today, there are bass players everywhere. But when I was coming up, bass players wasn’t the cool guys. They wasn’t the cool girls. Bass players was like at the bottom of the totem pole. Everybody wanted to play guitar or organ or saxophone. But nobody really wanted to play bass. I think we came up in that era that kind of changed that, once we got in there and started doing what you guys are doing now, changing the approach and changing the speed of things. I think those two things just made it a whole different ball game.

EA: Where did your phrase, “the wonder [power] of the one” come from?

BC: That, I think, was the most important part of music for me at the time, because I wasn’t holding the groove. I was coming over from playing guitar. It was about playing a lot of notes. For me, as a bass player, I wanted it to be different. I don’t want to just hold the foundation. I want to play the foundation and play around it. So James Brown taught me that. No, just hit that one. And then you can play around, whatever you want to play. But I always come back to “the one.” I think that was the best information for me because when I went to George Clinton, I really put that in focus. Because I was allowed to play anything I felt with George. But with James, who was really strict about, “Those three notes are great, just don’t play too many more after you play those three.” So it was kind of difficult, but at the same time, I didn’t have as much fun with James as I did with George. But I learned the basics about how to hold the groove. And that was pretty important at the time. And it stayed with me.

EA: How did you start your signature look, like the glasses and the hats and the stars?

BC: Actually, we started while we was with James Brown, but the difference was when we went on stage, we had to dress in suits and shoes, shined and cleaned. We had to be dressed in a uniform. So we all dressed alike, you know? James Brown was unified. He was more about everybody looking like one. So we would dress real freaky before the show and after the show, he didn’t mind that. But we couldn’t wear that stuff on stage. So, it really started when I got with George, when we were able to wear whatever we wanted to wear, do whatever we wanted to do, all those things you used to dream about; like, “Wow, it would be great if I could just wear this or wear that.” And I got the opportunity to do it with George Clinton.

The idea is like, I wanted star glasses. I wanted these outer space outfits. I mean, all of this crazy stuff like platform shoes and boots. He’s [James Brown] from the ’60s. It landed over in the ’70s where I was really breaking into what I was actually getting ready to do. James Brown was just the first thing I ran into that taught me how to be really disciplined and the ABCs of being a musician. So when I got with George, it was the whole other end of the spectrum. So I got a chance to act a fool and be one if I wanted to and look like one as if I wanted to. And all of that was cool. All of it was good.

EA: Here’s a funny question. What’s the most embarrassing thing that’s happened to you during a show?

BC: Have you ever broke a string while you’re actually performing on stage live, and this is the first time it happened to you? I just didn’t know what to do. I mean, I’m playing the solo and when I’m getting to the peak performance of the solo, a string breaks. And it never had happened before, so I didn’t know how to react. So what I did was, when it broke, I went straight to the mic and told the people that I broke my string and it would be a minute to get it together. And so I sat down on the edge of the stage, I took the bass, put it over my lap, and instead of having the roadie change my bass string, I did it myself because I didn’t know what to do.

And people just loved it. They were applauding while I was doing it. So, I learned if something ever happens, just calm down and maybe sit on the edge of the stage and figure it out.

EA: Did you have to play the song again?

BC: I got up and started where I stopped. I finished the song and we finished the show. The people were so accepting of whatever I was getting ready to do that they just accepted it and, and loved it, you know? I was kind of shocked and surprised, but they loved it.

EA: If you could have any song stuck in your head, what would it be?

BC: Any song stuck in my head? Oh, wow, that’s a good one. Wow, that’s a hard one. Well, you know what? What comes to me is “We Want the Funk.” That was stuck in my head since we recorded it. And any of the fans, you could say that to any of them, and they know what you’re talking about, you know?

EA: I mean, it’s probably been stuck in your head many times.

BC: [laughs] Yes, yes. Oh my God.

EA: How long did it take to record The Power of the One?

BC: Let’s see, it took about a year and a half.

EA: By the time it was released, it was around the year that COVID started. Did COVID affect recording? Was it more difficult to gather everyone for recording?

BC: Yeah, it was. That was a tough year, I think, for everybody, especially musicians that were used to doing things together. So we had to learn how to, just like what we’re doing now, [go] virtual, communicate, and record songs without being in the same studio. So we had to learn a lot and be accepting of the way we had to do things. We had to embrace the new way of recording, even if we didn’t feel good about doing it. We had to learn away because if we wanted this music to get made, this is the way we had to do it. And so it was a good way of challenging all of us. And I think we pretty much came through because in the end, it’s the music that really speaks louder than words.

EA: Did everyone record everything separately? Did everyone record their own part in the album?

BC: Not everyone, but some of the songs we got—like the rhythm section down in the studios—live, and a lot of the horns and keyboard parts, vocals were sent to the singer and they would go ahead and put their parts on and we’d talk about different arrangements, certain notes, on the phone and on the computer. I don’t know if you know Matthew Whitaker, he’s a keyboard player and organist; he’s a genius. I mean, he’s like Ray Charles…Stevie Wonder, he’s blind. He actually took me to school on the phone with recording, because he was telling me how to record his part on the phone. And I had never done that, you know? And so he talked me through it, and the next thing you know, we had all of his parts that he recorded in New York where he was at, and me and my engineer Toby, we sat here and just recorded it. So that was a new experience for me.

EA: Did Victor Wooten play on it?

BC: Yeah, he did

EA: So, your new album, Album of the Year #1 Funkateer, how long did it take to produce and finish it?

BC: I’d say about 13 months.

EA: Are you going to present it to the Grammys?

BC: Yeah. Well, the reason I did this whole Album of the Year #1 Funkateer is because I felt like—we’ve been around like the dinosaurs—for a long time, and we wasn’t getting no awards. So I figured I might as well give myself an award. Like Player of the Year. You wasn’t born yet when that one came out. But that’s what I felt about this one. The songs just meant so much to me and it was a process, it’s a part of your life that goes into each song. It’s just like every time you perform, that’s a part of your life. And when you go on stage to do that, it’s giving people a part of you. So I felt that same way with this album, you know? It’s a piece of me, a piece of my creativity of where I’m at at the time, and you give that to the people. It’s such a great feeling, to give that gift that you’ve been given. Remember how you felt when you first got your first bass?

EA: Yeah.

BC: Yeah, it makes you feel like that, you know? It’s healing, it makes you feel good.

EA: What’s one piece of advice you would give to anyone my age?

BC: I would say a lot of kids your age don’t really have the parental support that you’ve been blessed with. Kids that are coming up now, they need to get used to rejection. That was easy for me because I didn’t care what nobody said, I was going to do this, you know? But a lot of kids coming up, especially nowadays, it’s like they get so hurt and so downhearted when somebody says, “No, you can’t do this,” and “No, you can’t do that.” So, I consider you really blessed to have the support of your parents really digging you and helping you to get what your dream is. And so that’s the hardest part I think, is for kids to get over the rejection part. And they have to really work at, not only at practicing the instrument, they have to work on their instrument in their head, of how to accept things as they are and get your creative juices flowing and get them out some kind of way. And that’s the hardest thing. But what I like about your situation is your dad being there for you. And that’s such a blessing. I wish the whole world could get that. But unfortunately, we have to stand, a lot of times, by ourselves. And that’s tough for young musicians. Well, that’s tough for anybody but especially young musicians because they have a dream that everybody doesn’t agree with. That’s one of the parts of being a musician that we have to deal with very delicately because musicians are very sensitive. Tell me, I know [laughs].

EA: Just one last question about your newest album. Is the new album going to be on vinyl or is it just going to be streaming?

BC: It’s going to be on vinyl and CD and streaming.

EA: Everything.

BC: Yeah, we’ve got a really good team here and everybody seems to be supportive to get it out to as many people as possible.

EA: Well, okay. Thank you so much for coming.

BC: Oh, thank you for having me, Ellen. Gosh. I’m sure we’ll see you on the bass scene. And don’t forget, when you get ready to do that record call your uncle, alright? Thanks so much. Bye-bye.

EA: Bye-bye.

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.