When you’ve led a life like Cameron Crowe, you’re bound to keep everything. Backstage passes from touring with Led Zeppelin in 1973. Four hours of tapes from an interview with Pete Townshend at the Quadrophenia tour kickoff the same year. A legendary note from Gregg Allman written on Miyako Hotel letterhead in which he threatened to hijack Crowe’s interview (and almost his career). Not to mention scripts and prop pieces from Fast Times at Ridgemont High, Almost Famous, and Say Anything.

But Crowe nearly lost it all in 2025. As the Palisades Fire ripped through Los Angeles County, he came this close to seeing his house—and six decades worth of treasures from his storied career across film and journalism—burn into oblivion. The flames miraculously extinguished in his driveway. And in another stroke of luck, he had turned in the manuscript for his memoir, The Uncool, just 24 hours prior, cataloging many of those memories into one defining collection.

“In a weird way, I was at peace with all that I would have lost [because] at least I wrote this book where I could access it all,” Crowe shared in a recent interview from his new abode (he still hasn’t been able to go home due to the toxic smoke), fresh off a book tour moderated by a host of friends and muses including Eddie Vedder, Kate Hudson, Sheryl Crow, and John Cusack.

Besides, Crowe said, shrugging, “How am I not going to remember what it’s like to be around Pete Townshend and David Bowie?”

Out now on Avid Reader Press, The Uncool is, in fact, a total misnomer. The incredibly detailed 322-page chronicle offers a portrait of one of the coolest people to ever have a byline or director’s chair. In many ways, it’s an addendum to his cinematic self-portrait Almost Famous, and much like that movie’s effect 25 years ago, someone right now is reading Crowe’s book and wanting to find their way into music journalism. Except nothing will come close to what Crowe was able to accomplish—or witness.

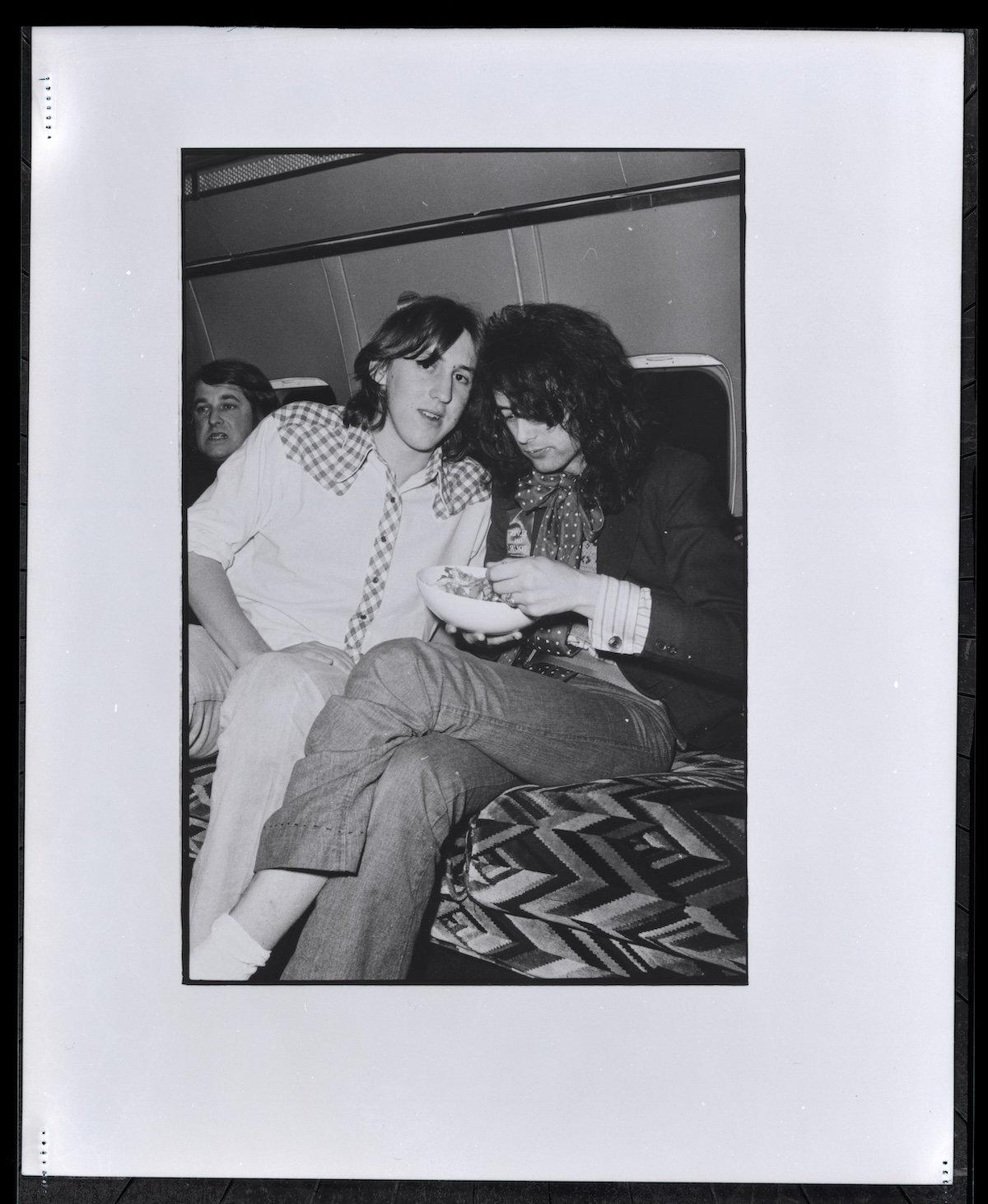

The Uncool is a firsthand tour through a mythical epoch of music and culture that died long ago, when interviews happened over a span of days, weeks, and months in hotel rooms, backstage corners, and even private planes. “The story was everywhere,” Crowe recounts in the book. It was the halcyon era of the golden gods of rock, and he had a front row seat.

As the book uncovers in glorious detail, the young scribe spent an unfettered 18 months with the notoriously anti-media David Bowie during this Thin White Duke era in Los Angeles. He traveled with Led Zeppelin (again) on The Starship during the band’s Physical Graffiti tour. He witnessed Gram Parsons and Emmylou Harris find a connection in real-time. He saw Bruce Springsteen’s notable Troubadour debut. And all before he had a driver’s license.

To this day, Crowe remains the youngest-ever contributor to Rolling Stone. After stints with San Diego’s underground beat paper The Door and music mag Creem, Crowe began publishing articles for Rolling Stone at 15, frequently ditching classes for feature assignments. On one occasion, he convinced a teacher to give him class credit for the Zeppelin assignment.

Of course, there have been some mishaps over the years, too. The worst interview, Crowe said, was John Mayall, though he fine-printed the situation as, “It was not because of him. It was because of me.” Crowe added, “I did this amazing phone interview with him and he was telling me stories about Eric Clapton. This was early on. I was so excited. But it was before the time of having the proper equipment. I had like a suction cup microphone that I put on the phone that recorded none of it. And if I remember correctly, I tried to do the interview again because I had not gotten one word. And I think the answer that came back was no way.”

Crowe also recalled that when he was sent to interview Steve Miller for Rolling Stone, “he cast me aside saying ‘I was too young to understand his complete musical knowledge, his complete musical scope.’ I thought he was joking. He wasn’t.”

Even so, in other situations, youth was Crowe’s advantage. “It was partially my age, partly that it was a novelty that I was a younger person who knew their music so well, and the fact that there were such fewer outlets,” Crowe rationalized about how he was not only able to get access to bonafide legends but also get them to break down the sex/drugs/rock and roll fourth wall for incredibly revealing conversations that showed a more human side.

In many ways he came at it as a fan and friend, going against mentor Lester Bangs’ advice of “don’t make friends with the rock stars—they’ll ruin you.” Bangs be damned, though, what Crowe did worked. After Rolling Stone published his profile on Led Zeppelin in 1975, editor Ben Fong-Torres handed over a box of fan letters sent to the magazine’s headquarters that thanked Crowe for the in-depth piece.

“If you were from one of those magazines [Rolling Stone, Creem, or Circus], they’d talk to you,” Crowe added. “And if you were young and knew the stuff, they would say things like, ‘Well that was fun. Why don’t you come to Tucson?’ And I’d be like, ‘Yeah, that’d be great!’ Like I could just do that. My parents would freak out. They’d be like, ‘What’s in Tucson? More promiscuity? What are they doing to you?’ I’m like, ‘They’re answering my questions!’”

Rock stars aside, Crowe’s family are the other incredibly amiable characters that often steal the spotlight in The Uncool. For as much as the book is a coming-of-age in rock journalism, it’s also just a regular coming-of-age tale about an atypical kid. In between the Rolling Stone sagas, much of the space is devoted to heartwarming recollections of the family patriarch, James, a celebrated military vet who moved the family from Palm Springs, California, to San Diego to embark on a real estate and telephone business career when Crowe was 13. There’s also great attention paid to his mother, Alice, a strong-headed teacher who wanted her son to become a lawyer but also gave him his first-ever interview with Cesar Chavez when he was a guest speaker in her class. A number of the daily aphorisms she doled out as motherly advice open chapters in the book.

But it’s Crowe’s sisters, Cindy and Cathy, who perhaps had the most profound effect on his eventual career. As the youngest of three growing up in a house where rock music was shunned, Crowe’s sisters would pass down their vinyl contraband with instructions on how to listen. When Cathy tragically died by suicide as a teen, those gifts (such as symbolically passing on the Beach Boys’ “Don’t Worry Baby”) took on new meaning. As Crowe says in the book, which he dedicated to Cathy, he quickly learned “the way music can serve as an emotional guide throughout your life.”

“I remember at one point, my sister [Cindy, portrayed as the fictionalized Anita in Almost Famous] said to me, ‘You shouldn’t write about Cathy and we shouldn’t talk about her openly.’ I think that was just because we were still kind of figuring our way through it and maybe I wasn’t ready to write about her effect on our lives yet,” Crowe revealed. “But I really put it together that I wouldn’t be here doing this, this thing that I love, if not for her gifting me with that passion. Because that’s the best, when somebody you love or trust says, check out this music. It becomes so much more personal than an algorithm.”

As Crowe continued his career, Cathy continued being a spiritual beacon. “I felt that through the years, Cathy was giving me clues as to who she was, and it led me right back to the music that she wanted me to hear before she died, which was the Beach Boys and the Tremeloes and this deep-feeling pop. I couldn’t stop writing about Cathy and I knew the book had to be for her. I got to introduce people to my sister.”

In Almost Famous, Cathy’s absence was symbolized by the empty chair at the table at the family home. As Crowe recalled, “I was so conscious of it. The cinematographer, John Toll, didn’t realize why I was being so adamant, as it kept getting framed out of the shot. He asked, ‘What the fuck is going on with the empty chair?’ And I was like, ‘You don’t understand, it’s everything!’”

It’s a theme that comes up again in The Uncool in several scenarios, including when Crowe was sitting in a hotel room with Gregg Allman for an incredibly intimate chat about the band’s survival after the death of bandmate and brother Duane Allman that wound up being on the cover of Rolling Stone in 1973. “I never forgot that Gregg had the empty chair, too, and that he scared the shit out of me by saying his brother was sitting in it,” Crowe remembered.

Later, during the opening night of the Almost Famous musical in 2019 at the Old Globe Theater in San Diego, there was an empty seat that was saved for his mom, Alice. She had passed just days prior and, in the end, remained so proud of her son for accomplishing his dreams (it’s she who often said the tagline, “it’s all happening”). In 2022, when the show hit Broadway at the Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre, Crowe was able to spread some of his mother’s ashes as a final sendoff. “It would have really made her happy that the show got to Broadway,” said Crowe.

Thinking of all the people in The Uncool who are no longer alive made Crowe careful about how to portray them in his memoir with tender loving care. “I wanted to kind of catch a moment before everything got set in stone about them, and just to have it out there, like Bowie, like Glenn Frey, even Gram Parsons—you know, here’s what it was like to be around them,” Crowe said.

Bowie, in particular, was a heavy character to look at in the rearview. “The most shocking thing to me was how close he was coming to dying, and I didn’t realize it as much as he obviously told me about later,” Crowe shared about witnessing Bowie’s dark, drug-fueled days as he made Station to Station in the mid-’70s. It was an erratic period he and Bowie discussed in hindsight when they reconnected in 2006.

“He survived, which is a gift. But, for all we know, there could have been a John Belushi moment during that time in Los Angeles, and that could have been Bowie’s legacy. I hate when that happens, when a legacy has to soak in a piece of misfortune,” Crowe shared, citing other examples like Marvin Gaye, John Lennon and, most recently, Rob Reiner.

“I’m really going through this now with Rob Reiner,” Crowe admitted. “It’s like, how dare you taint a body of work? And it’s going to take years for it to survive a messy, unasked-for, terrible, tragic ending.” As if following his own tenet, Crowe quickly extinguished the lingering sadness by offering a better memory of the late film director. “You know what’s interesting, when we were developing Say Anything, the producer James Brooks was really close with Rob Reiner, and he was the first person we went to and asked to play the father. He turned it down, but I realized how much he was on my mind writing Say Anything. When I think about Lester Bangs, too, my thing was always, he reminds me of Meathead.”

It’s stories like these we can only hope will make it into a part two, if Crowe ever decides to expand on the memoir concept to tell the tales behind the movie scenes (The Uncool wraps up just as Crowe’s film career is getting started). Next up on the literary front for Crowe, however, is a collection (also via Avid Reader Press) called Hamburgers for the Apocalypse: The Music Journalism of Cameron Crowe. “It’s kind of like a match set with The Uncool in a way, because you could read the articles that the book is about, the story behind those stories,” Crowe previewed.

For now though, making movies has taken precedence. “I want to make some movies now because I want to exercise those muscles. It’s been a while since I was directing. And I’ve just got all this stuff stored up,” Cameron shared. “I get a body rush remembering what it’s like to write something and have it be elevated in the hands of the right actor and with the right music. There’s no greater feeling.”

Crowe’s next confirmed project: a biopic on previous Rolling Stone interviewee Joni Mitchell. Crowe is naturally tight-lipped about it other than saying that filming will get started in 2026 and calling it “a dramatic feature with a lot of humor.”In fact, working on Mitchell’s movie gave Crowe the chance to really think about how he wanted to put together The Uncool. “I just keep thinking about when you strike that chord of personal writing. That’s what she’s about, she’s the queen of that. And with this book, I wanted to look back and kind of thank the people that opened doors for me, the people that trusted in me when they didn’t have to,” Crowe said. “But that’s the whole experience of the life journey—the little messages and things that pop up, and often it’s in music.”