Russell Simmons says he was “shocked” to learn T La Rock and Jazzy Jay’s 1984 single “It’s Yours” was produced by Rick Rubin, a white Jewish kid attending college at New York University and making music from his Weinstein Hall dorm room.

Simmons, who had already established Rush Management by the early ’80s, was well known in the blossoming hip-hop scene thanks to his work with acts like Whodini, Kurtis Blow and Run-DMC.

More from Spin:

- King Gizzard & The Lizard Wizard Hear A Symphony On New LP, Tour

- Wilco Festival Returns To Mexico With MJ Lenderman, Dinosaur Jr.

- Robert Smith and the Cure Get Wonderfully Lost on New Remix Album

He didn’t expect Rubin to be so…white.

“I just couldn’t believe it was him, because at first, I think, ‘Who’s the nigga who made the record?’ I kept saying, ‘No, the guy who made the record, who’s the nigga?’”

Once Simmons visited Rubin’s dorm and discovered his arsenal of beats, he was convinced they’d make great partners.

“Rick had a drum machine full of hits in my mind,” he says. “We became friends and I managed him and the Beastie Boys.”

Together with Lyor Cohen, who was already working with Rush Management, Def Jam Recordings began to take shape. They eventually convinced a radio program director from Adelphi University’s WBAU, Bill Stephney, to act as the label’s inaugural president, but it wasn’t a seamless process.

“Everybody was young,” Stephney says. “You don’t know what you’re doing really. You kind of do, but not really. You’d set up a meeting with them for 11 a.m. and no one was there. I come in all the way from Long Island, and there was nobody at the office, so I didn’t take it seriously but ultimately Rick and Russell came up with a couple of shekels for my starting salary and I began.”

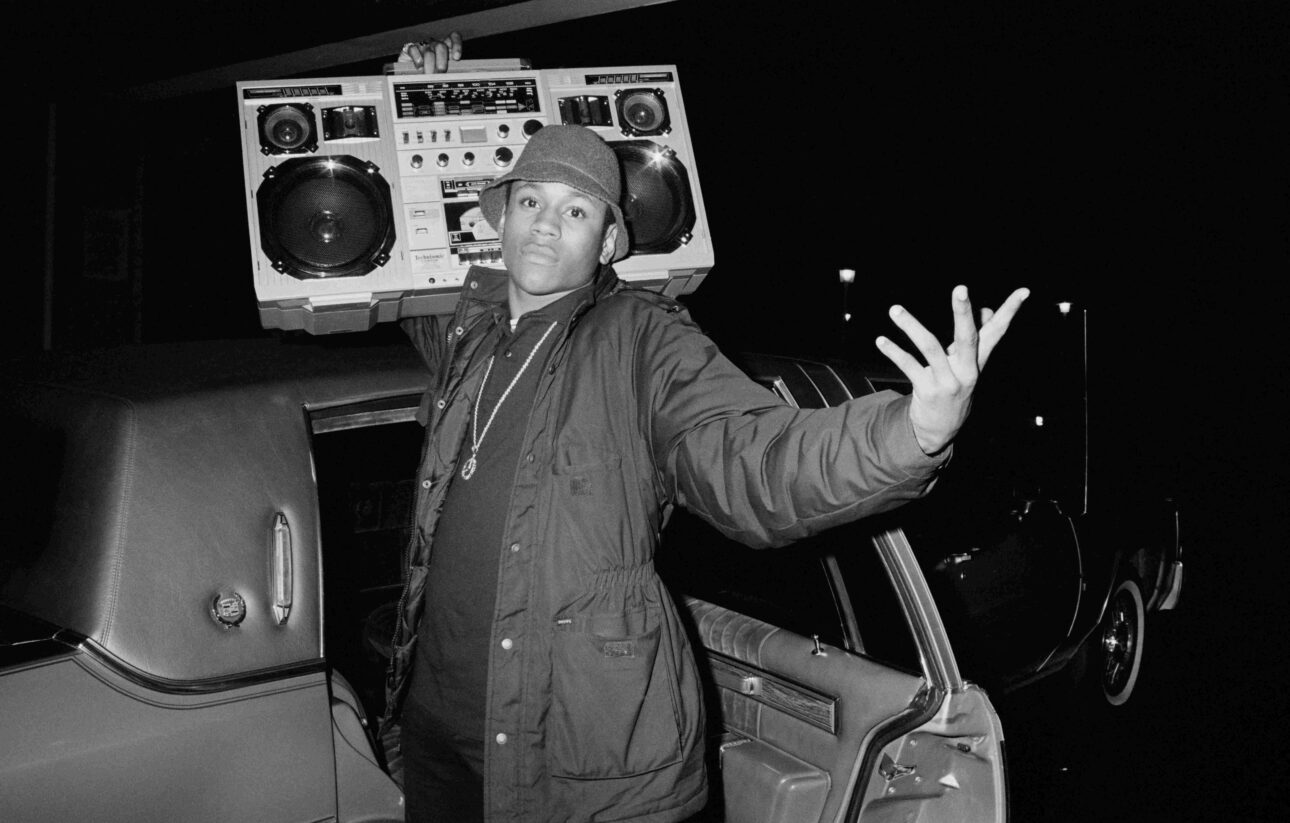

The first two singles with Def Jam catalog numbers dropped in ’84: LL Cool J’s “I Need a Beat” and the Beastie Boys’ “Rock Hard.” The success of both led to a distribution deal with CBS Records through Columbia Records the following year.

But according to former Yo! MTV Raps co-host Doctor Dre, whose group Original Concept was among the first to sign a deal with Rubin and Simmons, that’s when the trouble began.

“The climate at Def Jam was crap at the time,” Dre says matter-of-factly. “It always was crap because no one wanted to lead; everybody wanted to be a super artist, and Def Jam had grown a good reputation as far as doing that.

“But the moment they got the CBS deal and everything became extremely lucrative, that energy and that pureness changed. You were on the Queen Mary, but nobody was at the wheel, and you were always trying to find a direction and arguing with folks.”

Dre was particularly upset with Rubin, who didn’t seem to take much of a vested interest in Original Concept’s debut album, Straight From the Basement of Cooley High. In fact, it sat for two years until it was finally released in 1988.

“Rick wouldn’t get behind the record,” Dre says. “That’s not business — that’s personal. But everything in there became personal. Once the personal got with the business and it became too much, it got out of control.”

But, as Cohen points out, they were all in their early 20s and didn’t exactly have a Hip Hop Record Labels for Dummies to guide them in the right direction.

“We were making things up as they were happening, so there was really no mentorship or blueprint of what we were actually up to,” Cohen says. “There was a lot of learning on the job and freestyling, and trying to do the most tasteful and thoughtful thing.

“Sometimes ignorance is bliss. Our ignorance and making it up as we go was beneficial for some and probably not so beneficial for others.”

Chuck D felt by holding Straight From the Basement of Cooley High, it did Doctor Dre and the Original Concept crew a great disservice.

“Dre is really one of the unheralded stories of Def Jam, because he was that middle point that just kept tapping away at what Russell and Rick were starting to do,” Chuck D says. “Dre would go into the city every day and we would be scratching our heads like, ‘Why do you keep going into the city chasing these guys?’ Out of it came the Original Concept and I really felt that their album came out later than it should have.”

But Def Jam had been picking up steam and in 1985-86, the label was more focused on Beastie Boys’ explosive debut, Licensed To Ill, the first rap album to top the Billboard 200 and second to earn a platinum certification from the Recording Industry Association of America (it was certified diamond in 2015).

The Beasties launched the Licensed To Ill Tour in 1986 with DJ Hurricane on the turntables. The tour was a “hot mess,” according to Hurricane. Ad-Rock, Mike D and MCA were allegedly unhinged on any given day, and debauchery was simply the norm.

“It was just non-stop craziness,” Hurricane remembers. “The Beasties were just totally wild. We were getting banned from hotels and had to make up crazy names to check in. We all had the ugliest names. MCA was Nathanial Hornblower. I think Mike D was Fuzzy.”

Hurricane doubled as the Beasties’ bodyguard. At 6’5”, he was bequeathed the Herculean task of protecting them.

“We were in Liverpool and the crowd was throwing stuff at us,” he says. “Somebody threw a can on stage and MCA picked the can up and threw it back and hit somebody in the head, but Ad-Rock went to jail. The person said it was him that threw the can. They didn’t know the difference between him and MCA.”

That was only a microdose of what went on behind the scenes.

“I started DJing for them when it was really short sets,” he explains. “I was still on the road with Run-DMC at the time, so it wasn’t like I was with them constantly. When the [Beasties] tour started, the first show was in Missoula, Montana, and I flew my girlfriend out early because I was still out with Run-DMC. I told her I’d be there tomorrow and she was like, ‘These white boys is crazy.’ Turns out they’d locked her in a sauna with their friend Dave Scilken as a prank. Every day, there were jokes.”

Despite the monstrous impact of Licensed To Ill, it would be the Beasties’ only album on the label. Simmons speculates that internal struggles between Cohen and Rubin, and Rubin and the Beastie Boys, led to the split.

“Losing the Beastie Boys was the worst thing that happened to me in my music career,” Simmons emphatically states. “Rick is probably the greatest producer that I’ve ever been in contact with. Rick had interest in all kinds of music, but at the time he wasn’t quite that way.

“With the Beastie Boys, he was very heavy-handed. He was always a producer of artists and their talent — not a record maker. But back then, he was a little more heavy handed. And the Beasties needed a little bit of liberation in their mind.”

Both Doctor Dre and DJ Hurricane think money — or perhaps lack thereof — played a bigger role.

“Rick and Russell didn’t pay them just like they didn’t pay me,” Dre alleges. “They didn’t pay anybody. When they got the Sony deal, nobody had money so everybody signed for very little, and then Rick got a quick return on what would sell. But once the big money came in, he became cheaper and cheaper and more distant and distant.”

Hurricane wasn’t surprised the Beastie Boys left, adding, “I think it was a wise decision because they didn’t get paid. If you don’t get paid, all you could do was leave.”

When asked about the claims that people weren’t getting paid, Russell Simmons rebutted: “I spent my whole life empowering people and always paying people fairly whether they knew their worth or not, from Kurtis Blow to Jay-Z or Kanye. There was never a contract that wasn’t fulfilled.

“The sad story of the Beasties is that Rick and them fell out. They owed an album to Def Jam and the incentive to deliver was the money we withheld. Eventually they decided they would rather leave with their new album and a release from their contract, which of course was owed to us, then take the money and continue to partner with us. They didn’t want to deliver on their part of the contract. It broke my heart. We kept the royalties in exchange and they got a huge advance and a new deal with Capitol.

“As for Doctor Dre, I never owed him a nickel.”

Even with the Beasties off the label, Def Jam continued to flourish. Bill Adler, their first publicist, witnessed it firsthand.

“The Beasties leave and, theoretically, they could’ve continued to be a giant benefit to Def Jam, but I’m telling you, Def Jam pretty much rolled along anyway. We had so much else going on under that roof; Eric B. & Rakim were killing it, EPMD were killing it, Big Daddy Kane was making records for us. Slick Rick was the other Def Jam artist with big records.”

Around late 1986, Doctor Dre brought a demo of Public Enemy’s “Public Enemy No. 1” to Rubin’s dorm, a promo they made for the radio station they were working for at the time, Adelphi University’s WBAU.

“I put the tape in the machine and played it for Rick, and he was like, ‘Yo, this is crazy,’” Dre says. “When Chuck is getting into the first verse, Russell grabs it out of the tape deck and throws it out the window. Russell says, ‘Yo, what’s wrong with you? This will never work. It’s just noise.’ Luckily we went downstairs and I found the tape.”

It was a pivotal move. Public Enemy wound up being one of the most impactful artists in Def Jam history, with multiple platinum albums, including the group’s sophomore effort, It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, released in 1988, the same year Rubin left Def Jam to start Def American.

Now, with Simmons back in L.A. and Rubin out, Cohen was left to steer the ship. Even with the success of Public Enemy and other Def Jam acts like LL Cool J, EPMD and 3rd Bass, the label was in trouble by 1992.

“There was a very cold period that I signed a bunch of bad acts, one after another,” Cohen admits. “Then I understood what happens when a record company doesn’t have a hit.

“I was spinning my wheels. Then I realized the key for Def Jam was actually the logo, and it was at that point that I had everything evaluated based on the logo. That’s the thing that pulled this out of the cold. There’s a lot of people who know how to be hot, but there’s very few people who know how to survive cold.”

Redman, a burgeoning rapper from Newark, New Jersey, who was just 22 at the time, came in like a bulldozer, shifted the compass and got Def Jam back on course. Cohen credits both him and Warren G for saving the label from sinking.

“It was without a question ‘Time 4 Sum Aksion’ by Redman,” he says. “I was out until the eight count and then ‘Time 4 Sum Aksion’ happened.”

Warren G was “critical” to landing the deal with PolyGram and severing ties with CBS Records (now re-branded as Sony), who still owned 50 percent of Def Jam.

“I was being thrown out of Sony,” Cohen remembers. “I actually shipped Warren G’s record [Regulate…G Funk Era] from Sony and they didn’t even see what was going on as I was leaving. It went on to sell millions of records and allowed us to go into PolyGram with enormous amounts of clout. Timing is everything, and I wouldn’t be here talking to you most likely had it not been for those two artists.”

Ja Rule, DMX, Kanye West, Jeezy and Ashanti are merely a sliver of monster acts that have come through Def Jam’s doors, while music industry luminaries Stephney, Cohen, Jay-Z, Kevin Liles, L.A. Reid, Paul Rosenberg, Joie Manda, Faith Newman and Julie Greenwald are among the executives who got their start at or passed through Def Jam. Current CEO/President Tunji Balogun is juggling a roster that includes Clipse, Big Sean, Frank Ocean and, two original signees, LL Cool J and Public Enemy. Recently, Def Jam signed LiAngelo Ball to a $12 plus million contract based on the strength of his debut single, “Tweaker.”

Lyor Cohen, now YouTube’s Head of Global, has fond memories of his time with Def Jam but is most proud of the people he got to work alongside, as is Simmons.

“I’m proud of the people that we empowered, that stayed in power, that went on to do something even greater,” Russell Simmons says.

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.