It began, like so many memorable music stories do, with a British icon and the younger upstart who loved his style. The icon was one Robert Palmer—brilliant, eclectic, a cosmopolitan gentleman of the world but criminally underrated. The upstart was a young troublemaker named Nigel John Taylor, the future bassist with Duran Duran.

“I got into him around the [1978] Double Fun album,” says Taylor, now 65, from his home in London. “I went to see him at Birmingham Odeon. It wasn’t quite as immediate for me as Bryan Ferry or Queen, but there was something about him and the way he was operating, with that blue-eyed soul thing he had going. By the time I met him a few years later, he had become one of the most interesting journeyman artists, equal parts style and substance. We just hit it off. I was pretty charming at the time, you know, and it was only natural to talk about doing something together.”

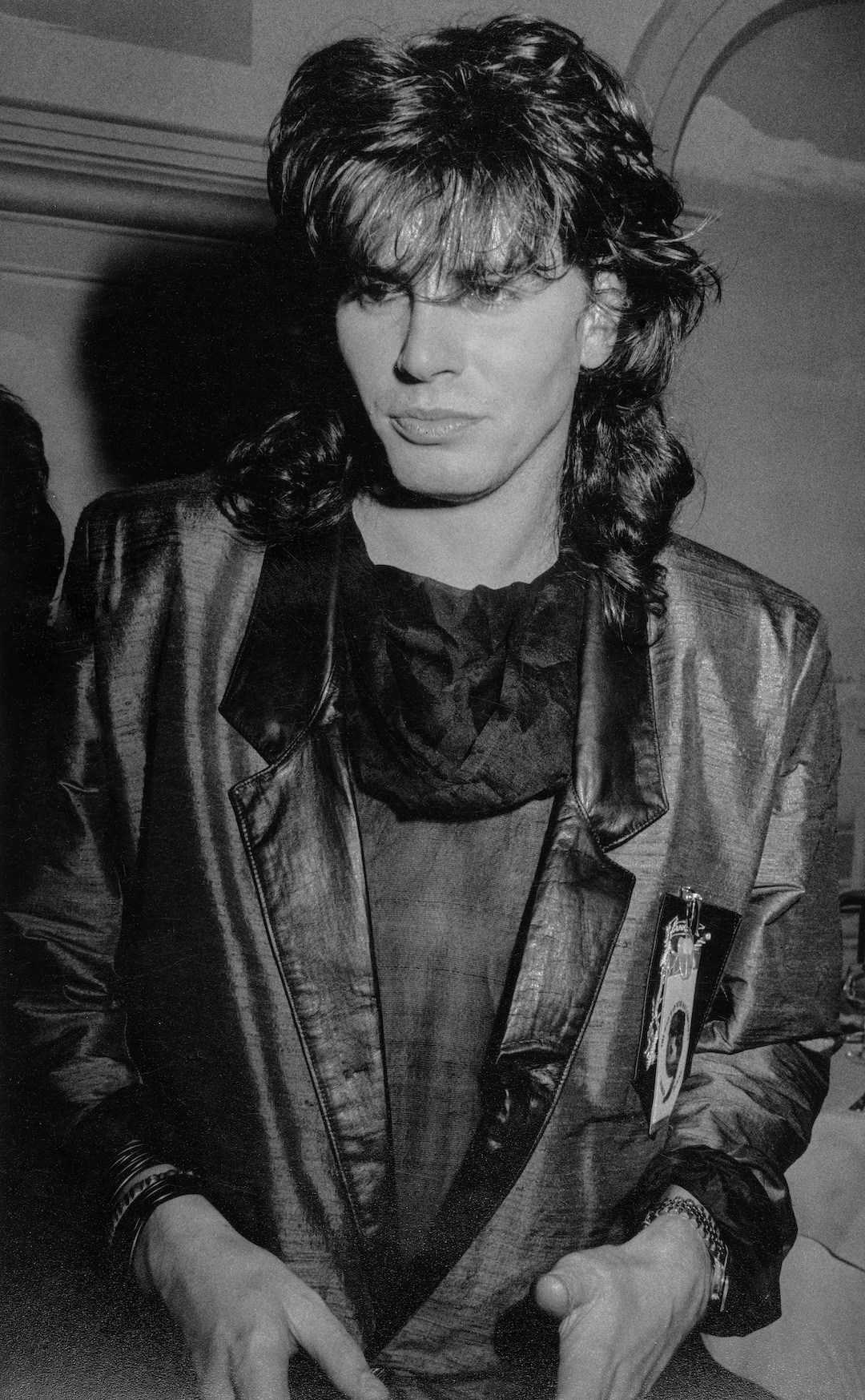

That something became the 1985 album The Power Station, recorded at the infamous New York City studio of the same name by Taylor and fellow Duran Duran guitarist Andy Taylor while the band was on a short but necessary hiatus (Simon Le Bon and keyboardist Nick Rhodes found refuge in side project Arcadia and that band’s atmospheric album So Red The Rose.) Wanting to explore a more ragged hybrid of rock and funk than Duran Duran’s glam-pop, the Taylors allied themselves with Robert Palmer and Chic members Tony Thompson—a formidable drummer—and Bernard Edwards as producer.

“The Power Station evolved out of an idea,” explains Taylor. “Originally, it wasn’t even going to be a band. We wanted to provide a sound service for different types of singers. But then Robert dropped in, having written a typically acute lyric. I don’t know many artists who could write lyrics that were as funny, interesting, and sexy, and then sing them with such verve and power. Very few, I guess. He brought a track called “Go To Zero,” and then another, “Harvest For The World.” Suddenly, we had an album. I found his music very moving, and at the time, Andy and I were like, let’s go and do something organic—organic, and immediate.”

Released in March 1985, The Power Station stands today as one of the definitive albums of the ’80s. A commercial success that peaked at No. 6 on the Billboard 200 chart, the album spawned two epic singles, including “Some Like It Hot,” which Taylor calls “an extraordinary piece of musical architecture” with its gated-drums reverb sounding like the collapse of a thousand shimmering stars. The decadent “Get It On (Bang A Gong),” an out-of-control cover of the 1971 T. Rex smash, followed.

Rhino Records is celebrating the album’s belated 40th anniversary with a box set featuring a brand new remaster of the original LP, instrumental outtakes, the band’s brief appearance at Live Aid, and a full show recorded during the summer of 1985 at The Spectrum in Philadelphia (sadly, without Palmer as lead singer—but more on that, later.)

“It was a definitive record,” says bassist Guy Pratt, a longtime Palmer collaborator who also performed with the band during a poorly attended Japanese tour in 1996. “The Power Station kind of invented that whole rock funk thing that became prevalent at the time. It’s massively influential. The whole idea was that Andy Taylor had never got to play rock before in Duran, and he had to have his Nile Rodgers hat on. Also the fact that you have Bernard Edwards there, and Jason Corsaro engineering. The gated reverb was allegedly invented by Hugh Padgham on that Peter Gabriel record where Phil Collins played the drums. But then I would say that it was carried on by Corsaro, because it’s the same snare sound that you find in Bowie’s “Let’s Dance” and the Power Station. It’s that studio. It’s the Power Station drum sound. And Tony Thompson.”

If the Chic contingency provided the funk, and the Duran membership the volatile glamour of superstardom, Robert Palmer contributed the album’s timeless spirit.

As a vocalist, Palmer had the uncanny ability to evoke both the gruff R&B grit of ’60s Stax and the wispy, vulnerable mystique of Brazilian bossa nova. In the ’70s, he had been one of the first English songwriters to experiment with African dance formats and bubbly Caribbean grooves.

“He was an easy guy to be around,” says Taylor. “Not a heavy dude at all, but took his music very seriously. He was funny, and wore life lightly. I never saw him lose his temper.”

“He was my mentor,” adds Pratt, who began his career with Australian band Icehouse. “It’s almost like I manifested it, because I had literally just joined Icehouse, we went off to support David Bowie and do these festivals in Germany, and Robert was on the bill. I went to see him in Nassau, and we wrote the song ‘Go To Zero,’ which actually got him the Power Station gig. I was 21. I remember he’d been in discussions with Jeff Beck about a concept that he described as doing a rock record with disco technology. In a way, that’s what The Power Station was about, because funk was almost discofied on that record.”

Here’s where our story becomes unpredictable. After the album was released, it was expected that a lengthy tour would capitalize on its success. But in July 1985, Palmer left the band, retreated to Compass Point Studio in Nassau and recorded Riptide, the biggest success of his career. Bernard Edwards was at the helm, and the visual for “Addicted to Love” included the tall, leggy models rigidly mimicking the motions of playing musical instruments—an aesthetic gambit that became forever associated with Palmer.

The band enlisted British singer Michael Des Barres and proceeded with the tour.

“You’ve got to remember that John and Andy were out of control at the time,” Pratt points out. “This was the height of Duran Duran and cocaine. Robert told me, ‘I saw the budget, and there’s $250,000 for wardrobe. That’s not wardrobe.’ He knew it was going to be a complete crash. That was also very Robert. He’d done the album, which was a fantastic thing for his reputation, and met Bernard. Now he wanted to go make his own record.”

The Power Station reconvened for a second album, Living in Fear, in 1996. A solid effort, it includes a cover of the Beatles’ “Taxman,” as well as a fascinating Bside: “Charanga,” an innovative combination of layered vocal harmonies with traditional Cuban dance music (charanga is an instrumental format from the 1950s featuring flute and rhythm section.) But the band’s subsequent tour suffered from poor ticket sales in Japan, the leg where Pratt came in as a bassist.

Known throughout his adult life for consuming copious amounts of alcohol and cigarettes, Palmer died of a heart attack on September 26, 2003, while staying at a hotel in Paris. He was only 54. “That life that he lived so well—sometimes a little too well—had caught up with him,” wrote Island Records founder Chris Blackwell in his 2022 autobiography.

“He’d gone to Paris to collect a pair of new shoes that he was very excited about,” says Pratt with a smile. “Which is so Robert.”

Fortunately, the music remains.

“We were driving recklessly under the influence when we made the first Power Station album,” reflects Taylor. “It was a mad time, and the horse was almost out of control. Andy and I thought that we were indestructible, that we could magically turn out the lights on these guys and make some magic. The truth of the matter is that Tony and Robert were so fucking talented. Stylistically, it was like conducting an orchestra. I was hanging on by the skin of my teeth.”