A flame-haired, dirty white-suited Tyler Childers strides with intent through a standing, whooping, exultant ovation in Nashville and takes the stage to give his rejection speech at the Americana Music Association’s annual awards ceremony. Freshly anointed as Americana’s Emerging Artist of the Year, Childers wastes no time ripping the genre a new asshole.

After declaring that even the word “Americana” itself “crawls up my spine,” Tyler spits on their parade. “As a man who identifies as a country music singer, I don’t feel Americana ain’t no part of nothing,” he said. “It kinda feels like purgatory.” The disgruntled, late-20s anti-Americana singer-songwriter then exits the Ryman Auditorium spotlight, stage left. That was 2018, with Childers going on to have billions of listens on Spotify — several hundred million plays per song in some cases. So, at least in terms of bank, he’s definitely emerged from purgatory.

Purgatory also happened to be the name of his most recent album — an LP co-produced by the singular Sturgill Simpson, whose own album, Metamodern Sounds in Country Music, had scored a Grammy nomination for Best Americana Album in 2014. That year, Sturgill was awarded Best Emerging Artist by the Americana Music Association, which in 2015 crowned him as Americana’s Artist of the Year, while also giving him Song of the Year for his psychedelic animist anti-monotheistic country-strummer, “Turtles All the Way Down”, from Metamodern Sounds.

But guess who later posted this: “I have never played a note of Americana in my life.”

Yessir: Mr. Simpson. What’s more (and also quoted by Whiskey Riff before Sturgill purged his socials), he puts the boot into Americana itself, and hard, writing that “the last thing music or musicians need is another ‘genre’ … especially one defined by empty semantics that throws us in an industry gutter appropriating any and everything with the slightest amount of steam for its own self-promotion/membership fees all while simultaneously placing a glass ceiling on our careers.” Instead of having anything to do with that made-up, cash-in, semantic category, writes Sturtgill, “I love all types of music and I mostly sing and play country, bluegrass, & rock n’ roll music.”

What’s going on? Why the hate? Putting aside the curmudgeonly ways of those two Kentuckians, the genre can get the cold shoulder even at the boutique end of town.

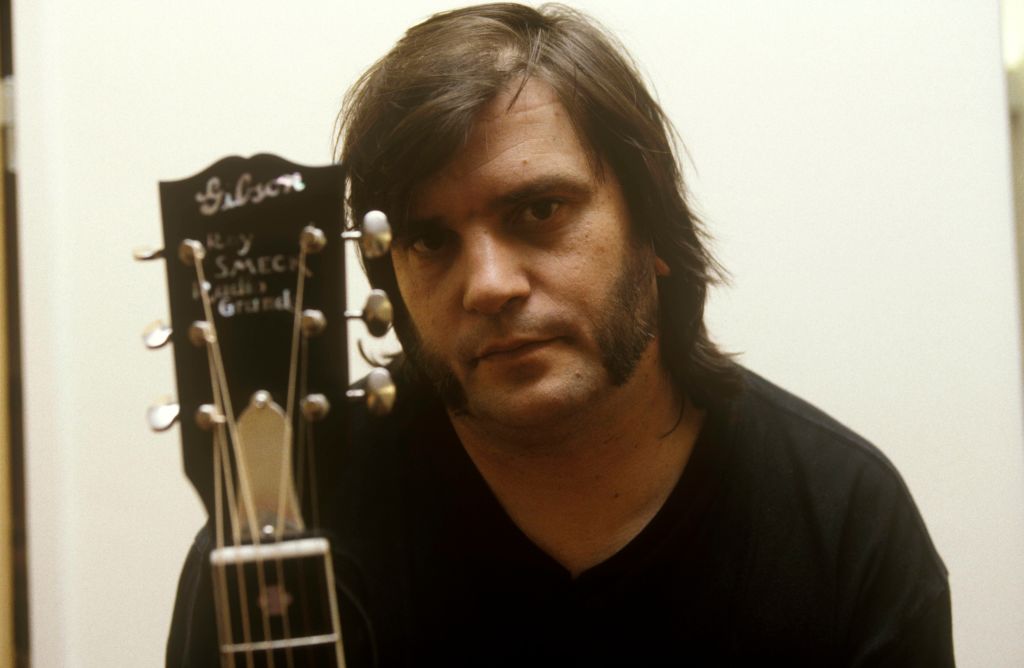

When I ask the Leonard Cohen of pickup trucks, Bill Callahan (known as Smog in his early years), to what extent he considers his music Americana, he says: “I don’t consider myself Americana.” When I ask Callahan what Americana is, he says: “I’m not one to put labels on music and ‘Americana’ is a word I don’t think I’ve ever said or written or thought.”

The dude’s jerking me around for sure. After all, Callahan is the guy who made a Zen musical experience in “Drinking at the Dam” out of cutting school to beer-up and yell near a bunch of jarheads; who slides from poignancy to bathos in “Our Anniversary”, the narrative of a drunk forced to stay home with his long-suffering woman on their big night when she takes his car keys, and who then quasi-hopes for a tired driveway fuck; and this is the the guy who nailed America in its ever-twisting, ever-unsettled, and ever-transfixing test of nerve with “Drover”, a song that gave the powerhouse Netflix doco Wild, Wild Country its title from Bill’s chorus:

One thing about this wild, wild country

It takes a strong, strong

It breaks a strong, strong mind

And anything less, anything less

Makes me feel like I'm wasting my time

Ain’t that America. But apparently this razor-sharp, Texas-based, country-tinged, minimalist poet of our strange land has never even thought, said, or written the word ‘Americana.’

So what do official Americana folk say about their zone of music?

Jed Hilly, Executive Director of the Americana Music Association — whose existence and honors Tyler and Sturgill shat on, figuratively speaking (while Callahan simply raised an eyebrow on his way past) — offers a prize wheel of definitions. Here’s a few quick answers from Jed:

“The contemporary form of American roots music.”

“Singers who can sing; writers who can write; players who can play.”

“People who were excommunicated from the country music world.”

In a slower mode, Jed spent years lobbying the publishers of the Merriam-Webster Collegiate Dictionary to have “Americana,” in the musical sense, entered into the official lexicon. And lo, in 2011, alongside such additions as “cougar” (as in Stifler’s mom) and “bromance,” Merriam-Webster added the word, with this definition: “a genre of American music having roots in early folk and country music.”

In 2010, the Grammys (also following lobbying by Jed and the A.M.A.) split Americana off from a dual category, with folk, to have its own prizes, and defined it, in part, as “contemporary music that incorporates elements of various American roots music styles… Americana also often uses a full electric band.”

In summary — contemporary, possessing elements of various roots… including roots, often acoustic, often electric.

Um… when Sturgill says it’s “defined by empty semantics,” is he… maybe… onto something? Of course not! But… what exactly is Americana?

Nashville independent singer-songwriter Lera Lynn, often described as Americana (and sometimes even “post-Americana” — God help us) and who doesn’t have a problem with the label, says simply that it’s “country without money.”

New Orleans’ Anders Osborne, a very rootsy guy who’s been roaming through rock and blues since the ’80s and whose distinctive singer-songwriter work gets labelled Americana, says he’s never pondered a definition. But give him a minute and he’ll think of something.

The first Americana chart was launched in 1995 (happy 30th!) by trade publication the Gavin Report (which folded in 2002). At launch the charters noted that for the new genre’s musical rankings, the “reporting panel was made up of some renegade Country stations, some AAA [Adult Album Alternative] stations, a few public and a few college stations who have one thing in common — a love for what has previously been called ‘alternative Country.’”

One of the first acts to make the Top Ten was the Delevantes (with their 1995 debut album, Long About That Time, which also won some other Best Pop Album award (so should the Grammy’s slot pop into their definition?). The band’s core is Mike and Bob Delevante, brothers originally from New Jersey, with the group rounded out for recording and touring with members of groups including the E Street Band, and Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers.

In a 1996 interview with the Clarion-Ledger of Jackson, MS, Mike Delevante tried to describe their approach, saying: “It’s not straight country; it’s not straight rock and roll; it’s not straight folk.” Mike, like many others in the gravitational range of Nashville but of an independent mindset, had found it hard to put a neat and tidy tag on his sound, because, until the Gavin Report’s chart appeared, “Americana did not exist,” he says, thinking back to how they used to pitch themselves for gigs or to get on the air before the term appeared and started to spread.

“Nobody called it that. At the time they were calling it alt-country, or they’d say, ‘What do you guys play,’ and it was ‘Oh, kind of roots.’ So they’d say, ”They’re a roots-rock band.’ They had all this terminology, and it depended where you were. In New York, it was like, ‘Wow, you guys are kind of country.’ And I was like, ‘OK.’ Then we’d go to Nashville and they’d go, ‘Man, you guys are a rock band!’ And I’d go ‘OK.’

Country, rock, bent folk, or whatever they were, Mike and his brother had moved to Nashville in the early 1990s, finding it a thriving, supportive, fertile place. “There were a lot of singer-songwriters. It was a great community, and there were tons of people coming in from L.A. and New York and other big cities looking to be in a community of songwriters,” says Mike. “Our first shows [in Nashville] were completely packed, and they were all other artists and all other songwriters. It was just so welcoming. We were like, ‘Man, this is great; this is awesome. And everyone would say, ‘Hey, let’s get together tomorrow and write a song.’ And we would. I remember meeting a band that had an amazing following and used to sell out a club Fridays and Saturdays, and they said, ‘Hey, why don’t you come open for us on Saturday?’ We’re like, ‘This is so nice!’ but I was thinking, ‘What’s wrong with them?’ Because New York had been so competitive.”

Such sincere invitations from established bands to come share their Nashville audiences were a real turning point, says Mike, leading to their own gigs, and building their own following — “snowball, snowball” — until “we get a writing deal from Warner Chappell. People are looking at us like, ‘Well, they’re not country but we think they could get a record deal because there’s enough interest in this style of music, so we’ll give whatever it is a deal.”

But this is before all the bits and pieces of American musical traditions that didn’t fit into some other neat slot or get airplay on kingmaker radio, got rolled into a new genre. “So they didn’t have a name for the style,” says Mike. “But there are key figures making money: Steve Earle was really big at the time. Foster & Lloyd were really successful. Nanci Griffith was big.”

And a theme became apparent, epitomized by Emmylou Harris. “She had a resurgence — she’s always doing that — but she started to not get played on country radio. And she’s country. But back then she was getting seen as a little bit of a rebel,” says Mike, tying it in with “her background with Gram Parsons” (the freewheeling, ill-fated, hugely influential exponent of what he called “Cosmic American Music” — oh dang, now I’ve can’t help but hear Tyler Childers telling Nashville’s gathered: “Cosmic American Music ain’t no part of nothing”).

Mike elaborates: “Back then Willie Nelson, Merle Haggard, Charlie Daniels — all those guys that would’ve been considered like real country — they don’t get played. Hank [Williams] Jr. They don’t get played on country radio.”

Mike laughs at how vexing it was. “It didn’t make sense. It was like, you can go into an executive’s office on Music Row — a publishing company or a record company — and they’d have that photo of Johnny Cash giving the finger to the camera and herald him as a hero, saying, ‘Isn’t he awesome!’ But would they sign anything that sounded like that? No way.”

Everyone at the labels wanted to get their wares on country radio playlists. Everyone still does, but now that’s in addition to getting on the web-era’s big-boy playlists, those of Spotify being paramount. Gatekeepers have not gone away. And country radio remains dominated by such heavyweights as iHeartMedia that owns more than 870 radio stations, including more than 100 country music stations — stations using supplied playlists. Skip around the stations now and you’ll hear the same handful of songs going to air.

“It’s very, very hard to break into,” says Mike, and its elusive promised land of wealth and fame steers music production into pandering to the gatekeepers. “A friend who engineered some of our stuff also worked on very, very country records,” says Mike. “He had radio programmers telling producers what kind of sonics they wanted on a snare drum. It’s crazy.”

Americana luminary Lera Lynn, cast in True Detective’s second season as a dive bar’s resident singer of low tales of life, says this is why she remains independent. Lera says she’s been approached by big labels who would likely spend a stack more on recording and promotion than she can possibly afford, and use their clout to get the tunes made for them on country radio and all the right streaming-playlists, but there’d be too much of a committee-approach to her music, and they’d want control that she doesn’t want to relinquish. Control over her sound and over the selection of songs for albums — and then who would she be? “I’m always trying to find a new way to say something,” says Lera, who plays a range of instruments herself as she hones in on a song that’s lived hitherto undiscovered in her inchoate sea of impression, instinct, eros, and vision. “And I just feel like it’s easier for me to find a way in when I’m alone and undistracted.” She isn’t talking from an ignorant or too-cool-for-school distance: her husband is a Nashville session musician who plays for the big end of town. She’d just rather do her own thing her own way.

This, says Jed Hilly. This. “Like I said, it’s singers who can sing; writers who can write; players who can play.”

That could be true for a lot of genres, though — right?

“Yes,” Jed says. “But it [design-by-committee blandification] is most prevalent in this world. If you look at Grammy’s Song of the Year nominees you’ll see the average number of songwriters is like six,” says Jed. In comparison, “Americana is like 1 point 9.”

And, wow, is Jed on the money. This factory-style manufacturing of country music comes into stark relief looking at Beyoncé’s album, Cowboy Carter. The single “Texas Hold ‘Em” was nominated for Best Country Song at this year’s Grammys. According to the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP), which distributes royalties, the single “Texas Hold ‘Em” was written by seven people: Brian Vincent Bates, Atia C. Boggs, Elizabeth Boland, Megan Buelow, Nathan John Ferraro, Beyoncé Gisselle Knowles, and Raphael Saadiq.

Also nominated for Best Country Song this year was Post Malone’s aptly titled “I Had Some Help”. The songwriters credited by ASCAP include Louis Russell Bell, Ashley Glenn Gorley, Jonathan Joseph Hoskins, Austin Richard Post, Ernest Keith Smith, Ryan Vojtesak, Morgan Wallen, and Chandler Paul Walters. Uncredited are unofficial 9th and 10th songwriters Tom Petty and Jeff Lynne who wrote “Learning to Fly,” which the Malone Industrial Unit blatantly rips off in “I Had Some Help.”

Sixty years back, when the Grammys introduced the Best Country & Western Song category (somewhere along the way the West was lost), the winner was Roger Miller’s “Dang Me”. Roger wrote it himself.

“In country, it ain’t three chords and the truth anymore,” says Jed.

To the flinty Bill Callahan, professional music as a realm of surprise and idiosyncrasy, of independent-spirited creation, is on the ropes. “It does seem like tastes are becoming homogenized and everyone is listening to the same few megastars,” says Bill, who blames in particular the social-media algorithms herding listeners into the same musical pens. “Instead of promoting true individuality it fosters hive-mind. Faux rebellion. Faked stances. We’re all being played for a bunch of suckers,” Bill says.

Anders Osborne (who, by the way, has now thought more about what defines Americana) spent about 14 years as a staff songwriter for the Nashville machine. “I was on Sony in the ’90s and it was a side deal to that.”

His credits include “Watch the Wind Blow By”, a number one for Tim McGraw co-written with Dylan Altman. “I discovered what I do is very useful for them as an ingredient to the popular songs they wanna write.” Another example is Eric Church, who “had heard one of my records, and brought me up. I brought in an idea, like ‘How about this?’ He needed a little lift in the chorus, so he added the little thing there,” says Anders. “It’s an ingredient that works for him.”

But not so much for Anders, long term. “It was almost something I could do,” he says. “But then after a while I started to lose my identity and things that I wanted to talk about were not as attractive to the market. So I pulled out eventually.”

If perceptions of what the market wants more of dictate what singers and songwriters ‘talk about’ through their work, the creative path isn’t forward into the great unknown but instead back to what worked before. “When you have a pop sensibility, which is what country is, it’s mainstream, tens of millions of people are attracted to it, then you have to follow trends — you can’t set trends. You have to follow. That’s what they do,” says Anders.

To him, Americana is in the naked and particular, not the blurred and generic. It springs from the individual, not the committee. It’s the expressive form of American troubadours, the singer-songwriters with the sensitivity and independence to observe, absorb, and share the specifics of their lands and families and losses and splendors: “It’s carrying on the torch of just telling the stories of what you know — Americana lives there: in the marigolds and the blue daisies and the mountains, and the starkness and the oceans, and the specifics of family dynamics in southern Illinois, and all the things that come with change, and then the longing for where you feel the most comfortable. And you keep telling these stories and telling the relationships in between and telling about the girl that you met, or the boy that just won’t call you back, even though you’ve been driving up to Madison, Wisconsin nine times, and he still won’t call you. It becomes very earthy, very everyday storytelling. But it has a drive, it has a twang, it has a blues, it has country. It’s not very urban, but you can be living in New York City and still feel this,” says Anders. “It’s the rocking version of folk music.”

With this in mind, I listen to Bill Callahan again. Specifically, to “Rock Bottom Riser” from 2005’s A River Ain’t Too Much to Love, the final album he recorded as Smog. Rather than offer an interpretation, I’ll just say that this poised and potent little song is more mythopoetic than particular, more symbolic than specific. Yet Callahan’s taut, controlled, delivery of this run of impressionistic imagery about a man struggling to resurface from the torrents of his foolishness strikes me as fine, distilled Americana. And it does so because of what really sets this genre apart from others. It’s literature.

Americana is literature as song. Not just story telling: AI writes stories; committees write stories. In one of our conversations, Jed Hilly said that some mark Dylan going electric as the dawn of Americana. And that can work. It certainly makes sense that Dylan won the Nobel Prize for literature, even if he said in his acceptance speech, “Not once have I ever had the time to ask myself, ‘Are my songs literature?’”). But Blood on the Tracks’ “Tangled Up In Blue”, for example, would be a near perfect work of Americana, of American short story telling, akin to Denis Johnson but in song, had Dylan only cut that pretentious verse about 13th Century Italian poetry.

Nevertheless, whether the song’s about dirtbags or psychedelic turtle revelations or a thousand other things, to have literary power — which really means having a life of its own — the tale needs gaps; mystery and confusion. Incompleteness. Contradictions. Tensions. And often this means it needs quiet moments, subtle shifts — spaces for the listener’s imagination to inhabit. Think of Nebraska, Springsteen’s 1982 masterpiece of Americana, and the reserve that gives it depth and power. Yet as grand as it is, Springsteen didn’t tour off the back of this album’s release, later writing that “Nebraska‘s quiet stillness would take me a while longer to bring to the stage.” Didn’t wanna play small rooms, boss?

Intimacy, and the ability to work with both quietude and its breach, is often essential to sketching, even creating, life in sound and verse. And when it comes to touring this can mean reduced earning potential, as the smaller-scale venues and shows suited to subtlety tend not to pay as much as stadiums or fields full of boozy good-timers.

Watching Bill Callahan play a side room of the Sydney Opera House, I once told a pair of dickheads at a nearby table to shut up or fuck off, because they were blabbing away to each other about work right through Bill’s pauses and gradual builds; his tensions and suspenses. Those guys were the exception at the show, so once they obeyed all was good again. But imagine trying to tell thousands of people to can it at some county fairground. Big shows suit big, loud, relatively unsubtle sound. So I ask Callahan if, in the pursuit of bigger crowds, festivals, and money, he’s considered going all ’70s-style Southern rock.

“While I love making my living with music, making ‘the most money’ is not a goal,” says Bill. “And letting dollars steer my boat is not an option. I don’t think it would even work if I tried. I’m meant to be in the exact position I am in. Smaller shows are nicer for me.”

But just as something inside Anders steered him away from writing-to-order in Nashville, there came a time when he needed to scale back, even if it meant less money. The turning point came playing a show with Jerry Garcia’s band and Bob Weir and his band at the Red Rocks Amphitheater in Morrison, CO. “I walked off the stage and looked at my manager and I said, ‘That wasn’t it.’ And he said, ‘What do you mean?’” So Anders explained: “This is not gonna do it. It doesn’t matter how much I push this direction of my life and career, this is not gonna do it.”

Where his heart is, where the art is, is in a return “journey towards the listening room” — more intimate venues where song as storytelling, as nuanced emotional experience, as Americana in full effect, will work best.

To be literature, a song needs irony — and not in some snide, too-smart-for-everyone way, but in the sense of how what someone says, in this case through song, ain’t necessarily so. As gritty and intimate as great music may get, there’s gotta be distances in it: longings and instincts and fears that don’t always agree with the words — characters and worlds that take on lives independent of the unreliable and incomplete storytelling, or picture-painting, that brings ‘em to us. That’s what distinguishes and elevates Americana. That’s “Tangled Up in Blue”. That’s “Rock Bottom Riser”. That’s Neil Young’s “Helpless”.

Princeton philosophy professor Alexander Nehamas defines kitsch as art that does all the work for the viewer except pay for it. Way too much music in widespread circulation is blancmange — insulin-spiking pap — including commercial country: songs about granddaddy’s shotgun and kissing by the pick-up, etc.

Guns and Silverado make-outs are undoubtedly splendid things and I wish for more of both, but, warns Nehamas, “if the experience of beauty is already complete,” as too many easy crowd-pleasers tend to be, we’re in the land of kitsch. And while kitsch might provide what Nehamas describes as “lowbrow sentimental bliss,” nirvana for many, some of us are just wired wrong for that shit. It makes me want to run through plate glass. Hence the allure of gaps in music, same with art that’s prose or on walls or screens. Glimpses rather than explanations. Music as experience rather than sappy storytime. But this is all a little too head-up-the-ass, hey.

My boy Nietzsche suggests that a religion is better understood by looking at the congregants and their behavior rather than focusing on the theological talk of priests. With this in mind I cross the Cascades, winding my way to the FairWell Festival in Redmond, Oregon, where tens of thousands of the faithful congregate to see Tyler Childers headline one night and Sturgill Simpson the next.

On the Saturday, a few hours before Simpson comes on, while getting a break from the sun in a shaded area with haybale seating I bail up a young man wearing one of those novelty bald wigs — boldly bald on top with red hair hanging long and free in a U-shape at the sides and back.

But it’s not a wig. He explains how a buzzcutting barber had found great mirth shortly after starting at the front-middle of his head and seeing a rustic clown emerge, so he talked Noah, as this guy’s name is, into leaving only the top shaved. Noah’s mom chuckled, too, and thought it so funny that she thought he should keep it that way for some family photos they were about to have taken. Beyond that, Noah’s clown head spread joy right, left, and center, so he kept shaving only that front-and-center patch while letting his surrounding red locks grow long and wild through the rest of school and after. It’s been that way now for about four years.

Noah’s here with family and friends from Heppner, a town of a thousand and some up towards Pendleton. “I work in a grocery store as a butcher. I cut meat and supply steaks and roasts for my community to live on and enjoy in their meals,” says Noah. “I never came up with a lot and most of my community didn’t either. So the music and the expression we’ve seen over this weekend really relates to me and, I feel, to the people like me.”

“What is it?” I ask. “What about it?”

“This is my first festival and it’s been mighty terrific. I haven’t had a bad interaction here. This is a collective of good people with good taste in music,” Noah says. “It’s a collective,” he reiterates, “of good people here for good music — and that’s exactly what we’re getting tonight.”

Listened to much Sturgill Simpson, I ask.

“I know one of his songs,” he says. “A song about a good dog called Sam that I know very well and I hope to hear.”

“You into Americana?”

“I was a very death-metal type of guy,” says Noah. “And then I had a girlfriend who came and introduced me more into the Americana type of music.”

“Death metal? And at first what did you see Americana as?”

“It wasn’t my rhythm; it wasn’t my beat. But someone came and showed me how to appreciate it.”

“What defines Americana?” I ask.

Noah glances at his little sister and their group, making sure everyone’s good. “A picking of the Southern instruments,” he says. “Not heavy on the bass or drums: they’re there to help carry through.” He gestures towards a show over the way, saying: “These are people that I feel most of America right now can relate to.”

Noah thinks for a moment. “I’m not knowledgeable or smart enough to say exactly what is Americana — it’s a feeling you get,” he says. “When you hear Americana you know what you’re listening to. In my opinion, Tyler Childers is good Americana.”