“Mothers who use cannabis are better mothers,” says David Lucito, who for decades has been preaching the multitudinous wonders of weed.

Unfortunately, David says, while he grew up in a “loving Catholic household” in Opelousas, Louisiana, his parents were “very anti-drug.” Growing up in such an environment, it took him 19 years to break free and smoke his first herb.

Nevertheless, before that momentous day, David had been a high achieving and well-rounded student at Opelousas Catholic School, showing great academic merit, acting with distinction in school dramas, starring on the quiz-bowl team, lettering in cross-country running, and becoming the student-body president. A week at Washington, D.C.’s National Youth Leadership Forum in Law left him so inspired he even recruited a federal judge to oversee his school’s student senate installation. David’s extracurricular life was also rich: from the age of 15 he worked at KOGM, an Opelousas-based music station serving the Lafayette area. “I was the on-air announcer, and I lined up your daily playlist with the selection provided by the music director, and put that right on the clock — down to the second,” he says proudly.

Yet, as David realized in hindsight, all his brightness and promise, his move to Lafayette to study humanities at the University of Louisiana, and more, had been afflicted by a great lack. For he had actually suffered profound deprivation as a child: denied the true and fulsome developmental empowerment that comes to infants via wombs and breastmilk steeped in weed. “Cannabis is a dietary essential,” says David, now in his early 40s. “Ganja babies do better.”

Once he got into the green, David made up for lost time, dropping out of the “higher-education racket” and devoting himself to better living through weed. David launched Legalize Louisiana while working as a DJ at Lafayette’s radio KCJB (“The Voice of the South”) and strove to legally and socially normalize this manna from heaven.

At a march through downtown Lafayette in April 2011, David told local news outlet the Independent that marijuana made his pharmaceuticals obsolete: “I really don’t mess with doctors anymore because all they did was feed me trash,” he said. “It was ridiculous. I was tired of putting 30 pills in my stomach three times a day to please doctors. I refuse to see them. I started self-medicating, and it has been wonderful.”

KCJB had folded earlier that month and with it David’s job. But he stuck to his higher calling, leading another cannabis march through the city a month later, holding aloft a verse from Paul’s Epistle to the Romans, reading: “For if their rejection means the reconciliation of the world, what will their acceptance mean but life from the dead?”

Even Bible quotes of puzzlingly questionable relevance failed to flip the state’s programming, however, with weed remaining a black-market drug. David turned down a graveyard shift at a TV station as he had no car.

So in 2012 David followed a woman to Medford, Oregon, selling vacuums under a bait-and-switch hustle, and then moved to Portland, all the while fighting the good fight as best he could to accelerate weed decriminalization and accessibility in the trailblazing liberal state. Yet things didn’t turn out as rosy as he might have hoped, largely because the Deep State had him in its crosshairs due to his Legalize Louisiana efforts, and after undergoing a time of trials and torments, David retreated back to the bayou to lick his wounds.

Were the quality of life, however, determined chiefly by the cost of weed, then David should have stayed in the Deep South of the Pacific Northwest because Oregon boasts America’s cheapest legal zonker. In the Beaver State, an ounce of primo-skunk, a.k.a. “high quality marijuana,” costs $211 on average, according to the Oxford Treatment Center’s handy national price guide, with “medium quality” coming in at $187. Meanwhile, in Louisiana, where the herb was only partially decriminalized in 2021, the prices rank amongst America’s highest: an ounce of primo will sting you $359 while mid-grade averages $258.

That’s for the bong-and-blunt-ready combustible green, which ain’t what it used to be, no sir. It’s a galaxy away from the “soft drug” that decades of activists said was nothing to worry about.

Up until the early ’90s, weed was generally around 3 to 5 percent THC (tetrahydrocannabinol: the fissile material, neurologically speaking, which hijacks and haywires the brain’s natural endocannabinoid system, causing people to mix jalapenos into Ben & Jerry’s).

It’s not like people didn’t spin right out even back then. “Are they vampires?” asked an extremely anxious buddy one night at an early ’90s warehouse party, eyeballing a goth trio across from us. On the wall above the latex ultravixens were projected scenes from Hammer-horror lesbian-vampire flicks.

“Sure hope so,” I said, perhaps unwisely, given my friend’s rising panic. Not long prior, he’d taken a monumental drag or four of whatever strain was called Buddha back then. We sat down and he hunched forward, gripping his legs and hyperventilating.

“They’re not vampires?” he asked again.

“No, they’re just chicks. And that,” I said, pointing at the projection above, “is just a movie.”

“It’s not real?”

“No — just a movie.”

“So none of this is real?”

I put my hand on his shoulder. “Hey, you’re real. I’m real. Those girls are real. We’re at a party. Everything’s fine. You’re just stoned. It’s gonna wear off. Let’s just sit here and take it easy while it does.”

He nodded and then nodded some more, then started shaking and looking at me in terror. “I can’t control my thoughts! I can’t control my thoughts!”

“You don’t have to,” I said. “They’re just thoughts. You can think whatever you want. But your body is here, sitting with me, and everything’s fine. It’ll wear off.”

Had he not gotten his shit relatively together but spiralled further until it seemed prudent to call an ambulance — as happened with another weed-wacked friend — he wouldn’t have been an isolated case. Of the estimated 100,000 cases each year of Americans aged 30 or less having their first psychotic break (a loss of contact with reality, typically involving delusions, paranoia, hallucinations, and disorganized thinking), up to a third of these profoundly harrowing experiences are believed to be cannabis related.

Mind you, back in the lesbian-vampire era, the average joint had a fraction of the mind-altering power it does now, for in our arms race of everything, marijuana has since been bred way, way, way stronger. Garden-variety plants have at least quadrupled in power since the Grunge era. Government studies class 15 percent and up as high potency, but the market is far beyond that with buds on sale packing upwards of 30 percent THC. And that’s just good ol’ unprocessed, greasy-to-the-touch buds.

Chomping into the bud market are shockwave-potency concentrates, solid forms of which include translucent sheets called shatter, as well as wax and resin, while oils and distillates are the fuel of the vaping era. (For readers already well up on newfangled stonedom, bear with me for the sake of those who still think y’all just pack cones and roll doobies).

Oils and distillates come in vape cartridges — “carts” as they’re known colloquially. These are cylinders, often glass, pre-loaded with between half a gram and a few grams of psychoactive goodness. Carts screw into lithium-ion-powered vape pens, which, at the push of a button, vaporize concentrate for inhalation. These are efficient brain-altering machines, used by upwards of 40 percent of young weedies. A gram of distillate can deliver up to 200 hits, depending on the duration of the inhalation, and in terms of potency, these new warheads pack megatonnage. Even buds come mad strong these days — towards 40 percent THC.

But the cart that David, for example, is vaping at present?

“Those would be closer to 90 percent,” says the former Mr. Legalize Louisiana, who sucks back more than a cart a week. “And you can get pure distillates, like 99 percent — that’s usually what I end up getting.”

Millions of other Americans likewise redline THC. And we should thank them for their service because these legions of daily, high-potency cannabis users have made themselves lab rats in a vast, uncontrolled, non-clinical, psychiatric, and neurological experiment.

Many shrinks — worrywarts that they are — point to a growing body of evidence that marinating the still-developing brains of young adults and adolescents in THC is associated with observable brain deformations and alterations, an array of cognitive and emotional impairments, and that it can trigger, or lay the foundations of, psychiatric disorders and derangements right through to episodic and even chronic insanity.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (looking at brain structure) and Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (looking at brain activity) have been carried out to compare what’s happening upstairs in young adults who routinely get high with those who don’t partake.

In terms of structure, researchers have found notable “exposure-dependent deformations” in users. These include reduced brain volume in mood-regulating areas and thinner and malformed components in areas that handle executive function, which is consistent with findings that stoners are impaired when it comes to decision-making and in carrying out tasks in a systematic and efficient manner. Researchers also found abnormal densities in parts of the brain associated with reward and motivation, suggesting that the brain is being physically re-engineered to crave gratification.

Looking at functioning rather than structure fits with the above: researchers have found subnormal levels of brain activity related to memory, attention, and executive function but elevated levels of brain activity around craving rewards. Scans also showed acute dopamine hyperactivity in the substantia nigra (SN) and ventral tegmental area (VTA), midbrain components in which dopamine dysregulation is strongly associated with psychosis and schizophrenia. Longer-term cannabis use is associated with blunted dopamine release — meaning anhedonia, or the loss of pleasure and joy in life.

The deformations and abnormalities occur in areas ripe with cannabinoid receptors — cell-membrane receptors to which cannabinoid molecules bind in the functioning of the human bodies’ endogenous cannabinoid system (ECS). The ECS regulates many internal functions that keep us in good order and capable. Here’s a handful: adjusting appetite to match energy needs; reducing anxiety at high-stress moments so that we can act as needed; overseeing the sleep-wake cycle; dampening pain and easing emotional reactions to pain, and modulating how memories are formed, stored, retrieved, and dispensed with.

Many shrinks — worrywarts that they are — point to a growing body of evidence that marinating the still-developing brains of young adults and adolescents in THC is associated with observable brain deformations and alterations, an array of cognitive and emotional impairments, and that it can trigger, or lay the foundations of, psychiatric disorders and derangements right through to episodic and even chronic insanity.

In order to please Seth Rogen, Miley Cyrus, Snoop Dogg, and other celeb proponents of the blunt life, marijuana and humans went through — in terms of chemical compounds, the cannabinoids — “convergent evolution.” This is the independent evolution of similar features or traits in unrelated, or only distantly related, organisms. Our ECS regulates us. Weed’s beloved cannabinoids, notably THC, are concentrated on the plant’s surfaces and most particularly on female flower heads, and they deter herbivores from chomping away, protect the plant from temperature extremes, and pack antifungal and antibacterial properties.

And they bind with cell membranes in our heads, with THC hijacking our cannabinoid systems with results ranging from spellbinding sex, adult-cartoon appreciation, Pink Floyd, and the munchies — through to brain deformation, slackerdom, and insanity.

While the overall incidence of cannabis-induced psychosis is low, the odds of a young person’s breaking from reality multiply with potency and frequency. A study published in the British Journal of Psychiatry, “High potency cannabis and the risk of psychosis,” finds that while one in about 3,300 will have a psychotic episode, when someone smokes high-THC weed daily, the odds can shorten to one in 278. Doctors and researchers describe this as a “dose-response relationship,” where the stronger and more frequent the doses of THC, the greater the risk that the response in the user will be madness. An international review of studies into risk thresholds published in Psychological Medicine concludes that “the risk of psychosis is significantly elevated with frequent, i.e., at least weekly, cannabis use.” High potency weed is ID’d as very much ramping up the dangers while other contributing factors include starting young, childhood trauma, and family history of mental illness.

Back in the lesbian-vampire era, about 10 percent of Americans reported smoking in the year to date. It’s now 20 percent — but that’s overall. Double it again for young adults, of whom up to a third hit it every week and an estimated 10 percent every day.

Canadian researchers looked at the health records of more than 13 million people in Ontario from 2006 to 2022, through three phases in the country’s relationship with weed: when it was mostly banned, when access to medical marijuana grew and recreational use concurrently spread, and after the legalization of recreational use.

During this time, more than 100,000 people were diagnosed with schizophrenia.

Before legalization, about 3.7 percent of new cases of this severely debilitating, lifelong condition were associated with serious weed habits (or, in the modern parlance, experiencing Cannabis Use Disorder). After legalization, more than 10 percent of new schizophrenia cases were tied to weed. Furthermore, from pre- to post-legalization, the incidence of psychosis not (or not yet) warranting a schizophrenia diagnosis almost doubled, jumping from 30 to a touch over 55 people per 100,000. The rate of people presenting at hospitals because of a weed problem rose almost fivefold.

In their paper “Changes in Incident Schizophrenia Diagnoses Associated With Cannabis Use Disorder After Cannabis Legalization,” the researchers note that the lion’s share of the market is now high potency: “The THC content of cannabis in North America has more than doubled over our study time frame, with more than 70% of legal dried cannabis sold in Ontario currently exceeding 20% THC.” And they look at where that has led: “Consistent with increasing cannabis use and potency, ED [Emergency Department] visits in Ontario for cannabis-induced psychosis and CUD have increased over time.”

In a related analysis of towards 10 million Canadians, “Transition to Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorder Following Emergency Department Visits Due to Substance Use With and Without Psychosis,” the researchers found that of those who wound up in hospital suffering a psychotic episode, the cannabis users amongst them were 84 times more likely than non-weedoids to transition to schizophrenia. Surprisingly, particularly for those of us accustomed to seeing meth-heads out of their fucking minds on the streets, the transition rate for weedies is higher than that of speed-freaks, cokeheads, boozehounds, and even poly-drug users.

Researchers found that of those who wound up in hospital suffering a psychotic episode, the cannabis users amongst them were 84 times more likely than non-weedoids to transition to schizophrenia.

Psychiatrist, psychotherapist, and further-educator of resident psychiatrists David Puder of Florida sees all this playing out up close. One representative patient is a man in his mid 20s. We’ll call him Tristan.

Tristan, like David Lucito, started adulthood all guns blazing. Then came an intertwined spiral of madness and cannabis. To more vividly convey the plight of Tristan and his family, Dr. Puder wants to go all stream of consciousness in describing what he has seen and experienced treating Tristan:

A young handsome man, pale blue eyes, gaunt but sculpted cheekbones, his frame still bearing traces of the Division I athlete he once aspired to be, now in the shower shrieking, trembling, pounding at hallucinated spiders in hellscape terror.

His THC-use heavy; potent THC; now years of use, and worsening.

His parents, competent in their own professions yet naively distraught, stand frozen as their son stamps his feet bloody against the porcelain tile, tears mixing with water as he tries to kill what no one else sees.

He turns to them staring at him in bewilderment, and yells, “How dare you!”

The parents have gone from hardworking normies, to angry at his provocations, to now just clueless, confused, at times erupting with commands, but mostly totally powerless.

His anger snaps them out of their haze, and they slink silently downstairs.

Someone knocks on his door, an unknown voice, claiming to be a psychiatrist, likely part of his parents’ nefarious plans to control him. With his last strength, he jumps out the window, and runs.

He is caught and restrained in a gurney, a crucifixion with large men, CIA likely, abducting him, stopping him from being able to scratch the arachnoid creatures feasting on his face. His parents nearby, betraying him, yes, much worse, malevolently taking part in his crucifixion. Sadistically smiling.

He hears: “Prepare 10/2/50 IM now.”

Later: awake.

Misunderstood. Alone.

Note: The someone who appears “claiming to be a psychiatrist” is Dr. Puder, and “10/2/50 IM” means an intramuscular injection of 10 mg Haldol, 2 mg Ativan, and 50 mg Benadryl. This cocktail is used to sedate people in a highly agitated or aggressive psychotic state.

“This was a very talented individual,” says Puder. “I’ve tried to get him to come to the gym with me. I’ve tried to connect with him. He no-shows all the time, but once a month his dad will drag him here to get his injection and then, slowly, if he doesn’t smoke, he’s not as psychotic. But when he smokes? He’s so much worse. So unmanageable. And then his parents are just like done. They’re so done.”

For seven years Puder has been hosting the Psychiatry and Psychotherapy Podcast, in which he and psychiatrists methodically assess reams of peer-reviewed research into mental illnesses and their various treatments. In his citation-studded show notes for an episode on cannabis and psychosis, Puder writes that of the more than 10 percent of young adults who use daily, they do so on average more than three times per day, “leading to a consistent intoxication during waking hours.”

This is more than 5 million Americans.

And more Americans now use weed daily than the number of us who drink daily, while those of us who do drink daily tend not to start in the morning — unlike the daily weedoids.

What an exciting experiment! We have unprecedented potency, unprecedented availability, and vast herds of young folk stepping up to show us what happens.

“With the high frequency of use, and the high potency of use, we will see an increase in people who are less functional, and we’ll see more conversion to psychosis,” says Puder. “Absolutely.”

But as much as shrinks and researchers ring alarm bells about the spreading — and especially frequent — use of hyperpowered cannabis, David Lucito knows they’re wrong and that the change underway is for the best.

Remaining supremely and permanently baked is vital for a host of reasons, he points out, not least of which is warding off a little-known yet pernicious condition called Clinical Endocannabinoid Deficiency Syndrome, a.k.a. THC deficiency. This grim ailment is responsible, Lucito reveals, for “fibromyalgia, migraines, cancer, everything. We’re all sick as fuck.” Hence the medicinal imperative to have, quote, “cannabis in your bloodstream from the time you’re a fetus til the time you, hopefully, never die.”

“Let’s say you have glaucoma; it’s good to keep in your bloodstream at all times. Let’s say you have cancer; it’s good to keep it in your bloodstream at all times. Let’s say you have anxiety; it’s good to keep it in your bloodstream at all times,” he continues. “What we’re looking at doing is supplementing the endocannabinoid system so that you always have cannabinoids active in your bloodstream. Delta 8 HHC THC-P is my current blend.”

What’s more, as much as Puder and his colleagues in the mental health profession want to get all dramatic about reefer madness, David Lucito knows precisely what caused his “misdiagnosis” of treatment-resistant schizophrenia.

“Psychotronic weapons. One of them is called Voice-to-Skull. It makes people hear voices,” David explains, noting that so-called schizophrenia didn’t exist until the 1880s, when emerging technologies made it possible to inflict such maladies on selected victims. “One of the first targets was Aleister Crowley. Another target was Charles Manson.”

The woman he followed to Oregon was not targeted, although a subsequent girlfriend heard voices. “She thought she was like a gifted psychic, but once I started hearing voices, I found out what all that’s about,” says David. “It’s all MK Ultra. Schizophrenia is a psychotronic weapon.”

The truth is out there, says David — not just buried in sub-sub-sub-reddits or 8kun, but plain for all to see in the august Oregonian (Portland’s 1850-founded newspaper of record). See for yourself, he advises.

And lo, a 2009 op-ed titled “Government Harassing U.S. Citizens” does indeed assert that:

Shadowy rogue elements within the military, intelligence (including the NSA), and intelligence contractor communities have been using psychological and electronic torture and harassment techniques against innocent U.S. citizens on American soil in clear contravention of the U.S. Constitution. This harassment and torture ranges from “street theatre” to “gang stalking” and “V2K” (voice to skull) microwave satellite transmissions. There is a clear pattern of this abuse around the country, as well as right here in Portland.

“From the day I stepped into Portland, I started getting stalked and harassed by people who were obviously on a military-grade, government-sponsored operation — a counterintelligence operation that has proliferated [on] our streets,” David asserts. “If I gotta get on the bus, everybody would be talking at me, telling me to kill myself, yelling at me to kill myself. Walking down the street, everybody knew who I was — that I was from Louisiana — knew what I was about — weed — and they told me to kill myself.

“That’s what Portland was like for me.”

The ‘soft drug’ argument won over America. At the turn of the Millennium, half of us thought that getting baked weekly or more put stoners at great risk of harm, according to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Now three quarters of us don’t think so, with a good chunk seeing it as harmless.

Society has caught up with ‘serious’ druggies in this regard, suggests the former marijuana addict, psych-ward alumni, and now philosophy professor Chris Fleming, who chuckles when he thinks back to mentioning his weed affliction during his early days at Narcotics Anonymous meetings. In a world of track marks, pill popping, and powder fever, no one had time for pot stories.

“When we were in our teens, pot was basically a joke,” says Chris, who got into weed in his early 20s. “Cheech and Chong, right? That was the representation of the drug. And then there was the Reefer Madness irony. At uni [college] everyone’s getting stoned watching Reefer Madness. I don’t think anyone saw that movie without getting high — that’s how you watched it: you’d seek out a VHS copy somewhere, get stoned, and watch. It was a joke. Everything about pot was a joke. And everyone said it’s non-addictive. That it’s a ‘soft’ drug — which has about as much scientific credence as alchemy.”

Even a dealer that Chris relied on for some time didn’t take it, or his dependent pothead customer Chris, all that seriously: “He mostly sold cocaine and ecstasy.”

Hence the reception Chris got at NA when he mentioned his weed habit. “It was like, ‘What are you doing here? You want more friends or something?’”

Yet for years Chris had lived in servitude to cannabis. Between a graduate scholarship and teaching pay, he’d been earning decent money, and he saved on bus fare by having students drop him near his dealer after class. Beyond rent, though, “all the money went to drugs,” he says. Chris estimates spending up to $60,000 in just a few years on marijuana. “One of the weird things about getting clean is you can buy shoes and stuff.” And while the consequences when he couldn’t score were not in the same league as opiate withdrawal, they were still nasty: “Crushing depression and an incapacity to do almost anything. Anhedonia: there was no pleasure in anything. I couldn’t concentrate. Strange things would happen to my vision: light sensitivity, flashing, like I was in a pre-migraine state,” Chris recalls. “Pot was completely necessary for me to function in the world.”

Like any self-respecting drug, it had become the cure for its own absence.

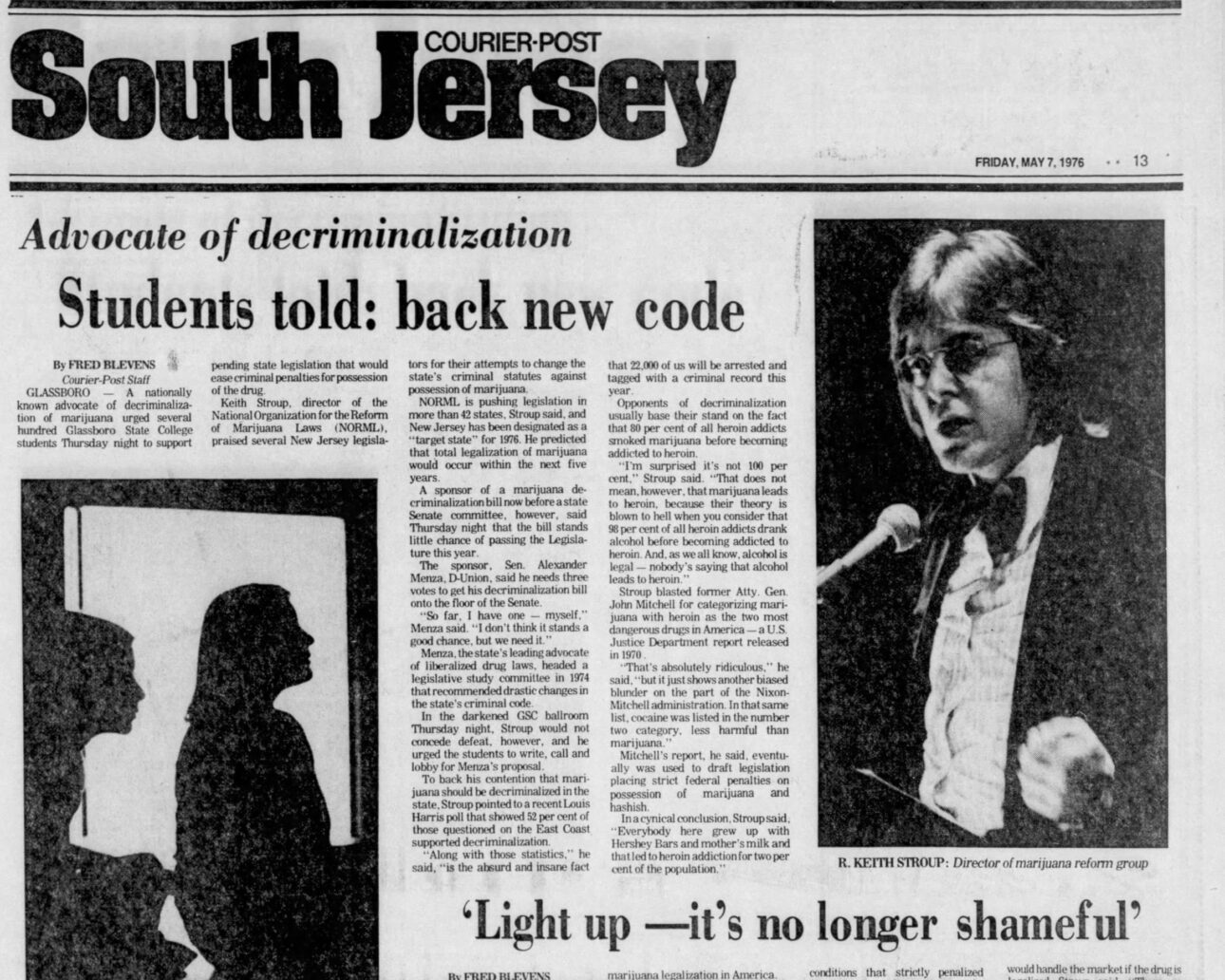

The pot lobby, mind you, thinks all this is ass backwards. The movement’s mothership is the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML). With $5,000 seed funding, and continuing bankrolling, from the Playboy Foundation, it was founded in 1970 by Keith Stroup, a lawyer in his late 20’s. “We do not advocate the use of marijuana,” Stroup told the Associated Press in 1971, “but we know of no medical, legal, or moral justification for sending those to jail who do use it. We believe the present marijuana laws cause more harm to society than the substance they seek to prohibit.”

NORML’s funding had ballooned to $450,000 by 1978, by which time Stroup was less straitlaced with his messaging. “The reason most people say they smoke,” he told the Washington Post, “and I’m really no different, is out of relaxation and fun. It’s a recreational drug, a social lubricant. The most natural thing in my life is to light up a joint and pass it around.” The next year Stroup stepped down as Executive Director, his position having become uncomfortable after confirming to the press allegations that President Jimmy Carter’s Director of the Office of Drug Abuse Policy, Peter Bourne, snorted coke at NORML’s end of year party in 1977.

NORML’s current mission, adopted in 2013, is “to move public opinion sufficiently to legalize the responsible use of marijuana by adults, and to serve as an advocate for consumers to assure they have access to high quality marijuana that is safe, convenient and affordable.”

With public opinion having grown much more positive about weed, and medical-use marijuana now legal in all states and territories except Idaho, Kansas, Nebraska, and American Samoa, and recreational weed allowed in 24 states, along with Washington, D.C., Guam, and the North Mariana Islands, the mission is going all right.

NORML’s Deputy Director, Paul Armentano, wants to keep it that way. Invited to comment on cannabis and mental illness, Paul first sends a collection of NORML reading matter — “Debunking Cannabis Potency Myths”, “Legalizing Marijuana Does Not Jeopardize Mental Health” — and a few others, most of which bear his name and all of which cite academic studies in support of NORML’s arguments.

When we talk a few days later, I raise with Paul the concerns of David Puder and the concerning findings of study after study after study.

“The data doesn’t support anecdotal claims that there is a causal relationship between greater use of marijuana and greater rates of psychosis among the general population,” says Paul. “It’s certainly possible that at the individual level there are some individuals that either have psychosis or a family history of psychosis, and that in some cases the use of cannabis and other psychoactive substances may exacerbate those conditions. But what we don’t see is on a population-based level, as more people use marijuana, greater rates of psychosis among the general population.”

Actually, while studies show only a slight rise in rates of psychosis in the general population, they certainly show a higher rise among frequent users of strong cannabis — and a significant increase in demand for medical help. In the journal article “Impact of Cannabis Legalization on Healthcare Utilization for Psychosis and Schizophrenia in Colorado,” researchers found that the spread of legal weed saw emergency department visits per capita for psychosis jump 24 percent.

“In jurisdictions with for-profit entities licensed to sell, legalization comes with a robust industry promoting high potency cannabis products, which have been associated with psychosis symptoms,” they write.

Questions about THC levels and mental illness, about the frequency of use and its relationship to mental health, about THC levels and mental illness, and about whether or not cannabis is now more dangerous than when NORML started lobbying in 1970, are dealt with by Paul by saying the research does not support what I’m getting at, or, if it appears to, then the study may have been methodologically flawed or have such serious limitations that adverse findings should be taken with due scepticism.

That’s not a very convincing rebuttal.

As for Dr. Puder’s and his ilk’s experiences and observations as treating psychiatrists and psychotherapists?

“It’s certainly plausible that psychiatrists might have a patient or two who’s suffering from bipolar disorder and uses marijuana and it’s exacerbated,” says Paul. “But that doesn’t mean that people who use marijuana are going to become psychotic or schizophrenic or suffer from other mental illnesses.”

It’s not guaranteed, no, but studies have found that cannabis users are up to 12 times more likely to have a psychotic episode than people who don’t partake. And for people who do have a psychotic break, those who use weed are 84 times more likely to transition to schizophrenia. And that’s the nightmarish summit of the problems; short of abject madness, there is the widespread diminishment of executive function, plus anhedonia, accelerated thinning of prefrontal cortices, and more.

Questions I raise about rising appetites for the rising THC levels get no traction, either.

“While there may be certain high-potency-concentrated products available for sale in legal jurisdictions, they’re not particularly popular,” says Paul. “They’re not what consumers typically buy. We know that because their purchases are tracked in these states, and what we see is the majority of consumers gravitate toward cannabis flower, which tends to be of a much more moderate potency — certainly far lower potency than those concentrated products.”

This seems to fly in the face of a wealth of research showing that high-potency concentrates are popular, especially with young adults, and it ignores that much cannabis flower is now high potency.

Given how authoritatively Paul Armentano of NORML interprets highly complex medical research papers, often seeming to dismiss or refute the authors’ findings, I am curious about his credentials. I mention seeing that Oaksterdam University, an Oakland, CA-based online provider of courses for budding weed professionals, has him listed as its Chair of Science.

“I was in the past,” he says. “I was doing that when I was living in the Bay Area, but I’m on the East coast now. Ah, okay. So it just wasn’t feasible.” As for his command of the fine points of medical research, Paul assures me of his mastery. “I have been working professionally on this issue and particularly on issues related to the science of cannabis for the last 31 years,” he says. “There’s probably not another person on earth that’s read as many scientific studies about marijuana as I have. I’ve written half a dozen books on marijuana and health. I’ve been invited to testify before the United States Congress on issues before marijuana. I’ve trained physicians at the University of Dartmouth Medical School on marijuana.”

“And your own academic background?” I ask.

“I have a degree in political science,” says Paul.

“It’s amazing, isn’t it?” Chris Fleming says. “And inevitable. The campaigners who spent decades arguing for its use have been forced to overstate just how benign pot is simply for rhetorical and institutional reasons — as a form of bargaining. The cases needed to be distorted in order for the case to get up.

“But, of course, once the battle is won, then you get bitten on the ass precisely because you have almost chronically understated any risk factor about pot. You’ve been forced to distort a case in order to have it come through, thereby ensuring that the [malign] effects will have to be minimized or ignored, because you’ve already ruled them out.”

Near the airport in Portland, OR, David Lucito’s old stomping grounds, I tour an indoor grow center. It’s a factory of the LOWD (Love Our Weed Daily) corporation, a craft producer aimed at “peak performance” cultivars founded by former Siemens engineer Jesce Horton.

After passing through a small, pungent room lined by people snipping off buds in eight-hour shifts, I’m taken through hyperfecund room after hyperfecund room, the abundance bathed in varying light combinations and always climate controlled. Brother David Lucito, I imagine, might be transfigured in these rooms. He might enter the Rapture.

Or he might just call the army; apparently he’s been contacting the armed forces a lot lately, hoping to find simpatico elements to work with on birthing the righteous trinity of force, religion, and weed. “What I’ve prepared for the military is military theory, linguistic field theory, just-war theory and concepts of operations for the forever war and the love singularity,” David explains. “Military and church need to team up to deliver the dietary-essential cannabinoid medicines to everybody.”

At LOWD I stop, mesmerized by a gold-lit jungle of plants with dense, misted buds that seem to unfurl like clouds of forming stars. “How strong is this?” I ask. “Like what percentage THC?”

“That’s about 37 percent,” says the guide.

In the mother room, I gaze at rows of “mom plants” that are manipulated to remain in a persistent vegetative state, so that the world may be filled with their clones.