Ruston Kelly was in the middle of a years-long existential crisis when he left his own body and watched himself sitting at his piano.

An astral projection.

He was sober, clean from drugs for a few years.

An apparition approached him while he floated. It was Jesus. As the figure came closer to Kelly, the musician felt a sense of calm wash over him.

“I understood a sense of, it wasn’t bliss, and it wasn’t even joy, it was complete equanimity,” he says during a video call from his home in Nashville. “There was a oneness to what had been, what is now, what would come.”

Then, when Kelly came to, he realized he had been crying, his hands raised while he sat on the piano bench. And he knew he wasn’t alone anymore, that whatever he was going through was over.

“There wasn’t really a call to be anything other than a student again, but a student of my own spirit in relation to knowing that I belong to someone,” he says. “I mean, that changed everything.”

Kelly swears to me he isn’t a religious man, at least not in the traditional sense. He’s not a member of any branch of Christianity, nor does he necessarily want to be. “When we start talking about these things—especially when it comes to public-facing lines of work—speaking about God and speaking about religion seem to be synonymous, but I didn’t have a religious experience,” he says. “I had an experience that was just my experience. That’s the only way I can put it.”

Over a multiyear period, Kelly, despite releasing three albums—Dying Star (2018), Shape & Destroy (2020), and The Weakness (2023)—felt like he had lost his voice. You’d never know it by listening to him sing during that time. But to him, he experienced an immense loss between the physical and spiritual link that comes with singing, a sort of voice dissociation. “I did not feel a connection to my main form of artistic expression,” he says. “I couldn’t sing with a fluency that seemed to have always come from a natural ability to express my soul.”

He couldn’t sleep. He broke down in tears. He begged and prayed to whatever higher power there was to get his musical gifts back. “I felt that I was being punished for all the ways that I had abused something that was important and freely given,” he says, referring to earlier days of drug addiction.

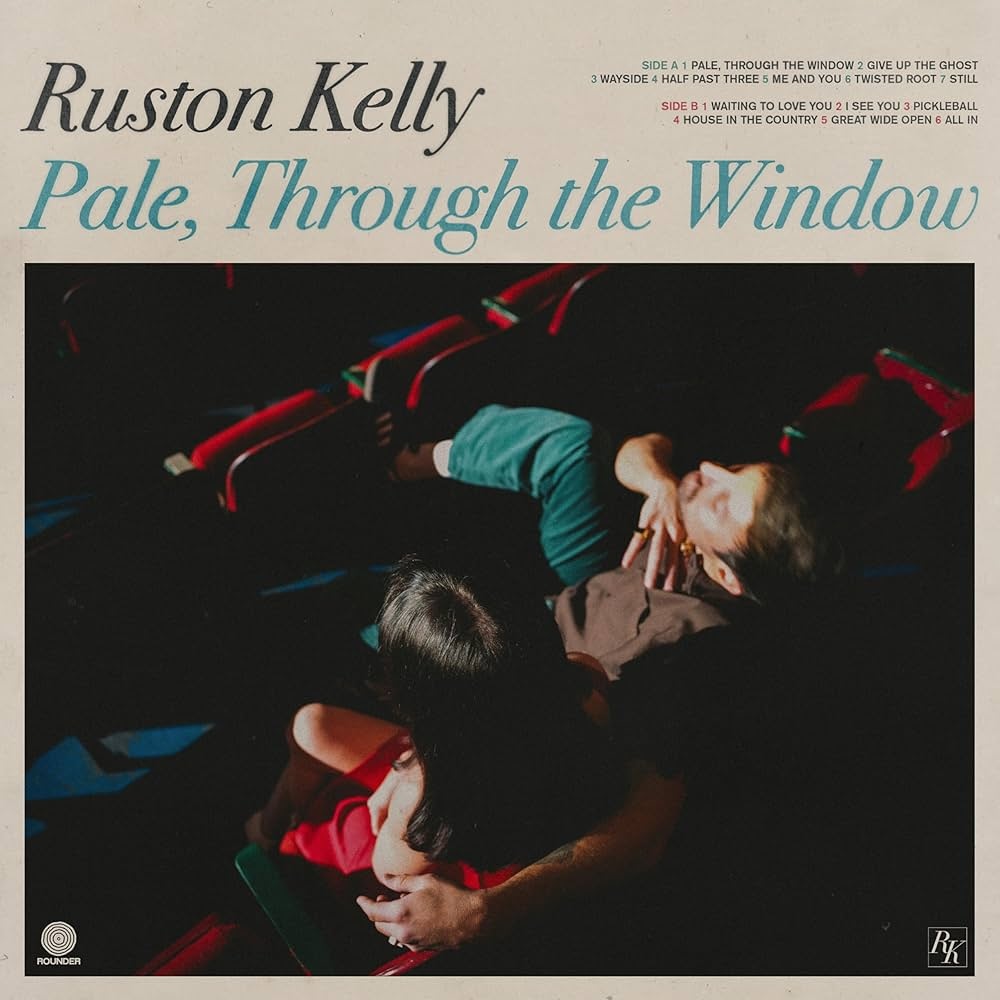

His new album, Pale, Through the Window, is about that experience.

Kelly approached writing this album, released September 12, differently than his previous records.

“I was really getting frustrated with having this incredible experience, and not being able to funnel it into a creative conjecture about what it was,” he says. “I wasn’t able to pull from that thread that I always pulled from. I kept trying, and it just seemed like everything came out trite, and this was anything but a trite situation. I knew I was going to have to write from a different muscle.”

Kelly says that his songwriting technique for Pale, Through the Window became less about the discipline and craft of songwriting, less about metaphors and abstraction, and more about telling a simple, straightforward story. He didn’t start writing until two weeks prior to pre-production. He had faith that the words would come. And they did, more easily than they ever had before.

“I was assaulted by the inspiration for what the album was and knew that it was going to be very simply about this spiritual experience and about falling in love on the heels of that.”

Kelly’s referring to his current girlfriend, Tia Cubelic, whom he met while on vacation to Pawleys Island, South Carolina, in 2024, where their first date was a game of pickleball, inspiring the album’s track of the same name.

But the 37-year-old wasn’t always destined to be a singer-songwriter.

Before becoming an Americana, or “emo-dirt” musician, as he describes his genre of music, Kelly was a junior Olympian and seven-time state champion figure skater.

From the time he was 8 years old until he was 15, Kelly was steeped in the deeply competitive, and in his words, toxic world of figure skating. With his parents’ permission, he moved from his home in Georgetown, South Carolina, to Ann Arbor, Michigan, to live and train with a husband-and-wife coaching team. While his gift for the sport was apparent to everyone who watched him skate, the dysfunction that was happening behind the scenes wasn’t.

Kelly’s coaches, who had taken legal guardianship of him, forced him to train intensely for eight hours a day to pursue his figure skating dreams. After practice each day, however, they seemed to want nothing to do with him.

“They never really provided any legal guardianship in the way of food or picking me up from school,” he says. “So I had to kind of toughen up.”

As an escape from the instability of his situation, Kelly began learning Blink-182 and Nirvana songs with the guitar his father had given him for Christmas. He eventually began writing his own songs as a way to deal with his stress and conflicting feelings.

“I would shut myself in the room and start expressing my own feelings musically,” he says. “I found a way to have relief from something that’s difficult for me to articulate to anyone, even myself, but then to also make some sort of sense of it.”

It was self-preservation through self-expression, he says.

Kelly knew he would have to make a decision about his future: either tough it out and figure out how to take care of himself so he could keep skating, or tell his parents about the abuse.

He eventually told his parents and walked away from the sport for good.

Because of his father’s work, Kelly’s family moved a lot. During high school, they had relocated to the small town of Wyoming, Ohio, where Kelly became known as the “guitar guy.” Music, he tells me, was in the fabric of the friendships he formed there; not just listening to it, but performing it. Together with the group of friends he jammed with, he attended a Dave Matthews Band show, Kelly’s first concert, describing it as the “ultimate extension of what we do in our parents’ basements and garages.”

But it wasn’t until the Dave Matthews Band came back to Wyoming the next year that Kelly began to think about pursuing music professionally. Attending the show with his older brother, Kelly remembers his sibling leaning toward him, pointing to Matthews onstage and saying, “You’re going to do that someday.”

After a brief stint in Belgium, where his family had moved later, Kelly went to Nashville with his sister at 17 and began playing with a local jam band called Elmwood. Some music executives noticed them while playing at a bar, and within a week, they were signed to Paradigm Records and began touring.

It was while Elmwood was touring with alt-rock group O.A.R. that he got hooked on drugs. A fellow band member introduced him to amphetamines to help with Kelly’s ADHD.

“On the onset of that chemical hitting my bloodstream, I felt two things: One was that I felt normal for the first time in my life,” he says. “And the second was, I never want to stop taking this.”

When he got home from the tour, Kelly got a prescription, and the bottle was gone in two days. He felt like he could do anything, until the amphetamines wore off. Then, he says, he would feel worse than he did before, with new feelings of depression, hyper-anxiety, and lack of self-worth.

“It got to where I was taking handfuls of it,” he says. “I had to take multiple pills to even function.”

By the time Kelly was 22, he began to feel restless with the direction his career was going. “I liked playing jam band music, but it just wasn’t part of that initial expression of making sense of the world,” he says. “And I wanted to do something that had value other than attempting to tap your foot.”

Kelly quit the band and took with him the songs he had written that would become, as he describes it, the early steps toward making his own records.

In 2013, “Nashville Without You,” a song he co-wrote with Kyle Jacobs and Joe Leathers, appeared on Tim McGraw’s Two Lanes of Freedom album.

As he pursued his solo career, Kelly’s drug addiction worsened. When amphetamines stopped working, he moved on to cocaine. While he says he partied a lot with friends, it was when he was alone in his home writing songs that his drug abuse really got bad.

“I think at the time I felt such a calling to do what I’m doing now, but when I was on all of those pills, I could never stop doing it,” he says. “And I think I had associated creativity with something that was broken, and that I could at least impart something of beauty and meaning into a broken situation. But you end up drinking your own bathwater because you’re trying to heal something while also breaking it at the same time. I wish I’d never taken that pill. But that’s the choice I made.”

He knew his addiction was taking a toll on him and his family. As much as he wanted to get clean, he found it nearly impossible. “That chemical had such a vicious hold on me that it almost, in a demonic way, reared its head,” he says. “And I attempted to shun my entire family, and I’m so close with them. I saw it break my mom and my dad’s hearts in front of me. The things that I was saying that I would never say in a million years, in the way that I was saying them, and the destruction that was coming out of my spirit, seeing that land on people who have done nothing but love you in their best efforts.”

Kelly overdosed in 2015, which put him in the hospital. He then went to rehab, and he was able to stay sober for a period of time. He then began dating country artist Kacey Musgraves in 2016, and the couple married in 2017.

During his three-year marriage, Kelly relapsed. “It was a single night,” he says. “I woke up with a sock full of pills and was like, all right, never again. And it’s been that way since.”

It was around this time that Kelly lost the spiritual connection to his voice, spiraling him into his long, emotional crisis.

Thanks to his out-of-body experience, Kelly not only got his voice back, but he learned to let go of his painful past and gain a new perspective on life and his songwriting.

“Letting go of the past, letting go of the tropes that I’d written into my own script, you know?” he says. “Maybe I’m not that great a scriptwriter for myself. There is a plan above, around, and beyond what I could imagine for myself. There’s more breadth to the way I’m experiencing my own reality. And surrendering to that is the most freeing experience I’ve ever had to date.”