“When we’re writing a song or recording a song, I think we have a pretty good internal quality control of, ‘Is this good?’ or ‘Is this exciting?’ versus ‘This feels forced’ or ‘This doesn’t feel natural,’ ” Mac McCaughan says, explaining how Superchunk have, maybe consciously or maybe not, maintained their high musical standards across 36 years.

We’re sitting outside Gray Squirrel Coffee Co. in Carrboro, North Carolina, just a few doors down from Cat’s Cradle, the storied Chapel Hill venue that has hosted many a Superchunk show since their earliest days. In fact, the club has been a constant in McCaughan’s musical life for even longer—he’s played there with his high school band, his pre-Superchunk projects, and of course, countless times with Superchunk at the Cradle’s various incarnations over the decades.

It’s fitting that we’re discussing Superchunk’s new album, Songs in the Key of Yikes, within earshot of one of their most frequented stages. After almost four decades, the North Carolina indie rock stalwarts remain one of those rare bands where the consensus, amongst both critics and longtime fans, is that their recent material rivals their beloved catalog—no small feat when that catalog includes classic indie albums like 1991’s No Pocky for Kitty and 1994’s Foolish, and indelible garage-punk anthems like “Slack Motherfucker” and “Hyper Enough.” Since restarting in 2010 with Majesty Shredding, which followed a nine-year break, they’ve been incredibly consistent. But that consistency is also in doing something that sounds perpetually combustible and on the verge of careening out of control. It’s a beautiful juxtaposition: being reliably explosive.

McCaughan identifies this combustible quality as essential to punk rock itself. “If something feels too tightly wound, it loses a little bit of energy,” he explains. “When you hear ‘Neat Neat Neat’ by the Damned, or ‘That’s How I Escaped My Certain Fate’ by Mission of Burma, you’re just like, ‘Oh my god, are they even gonna finish this song? This sounds insane.’ You can’t try to do that, but you can kind of hope to achieve that energy. You probably can’t get there on every recording or every performance, but when you can, it’s beautiful.”

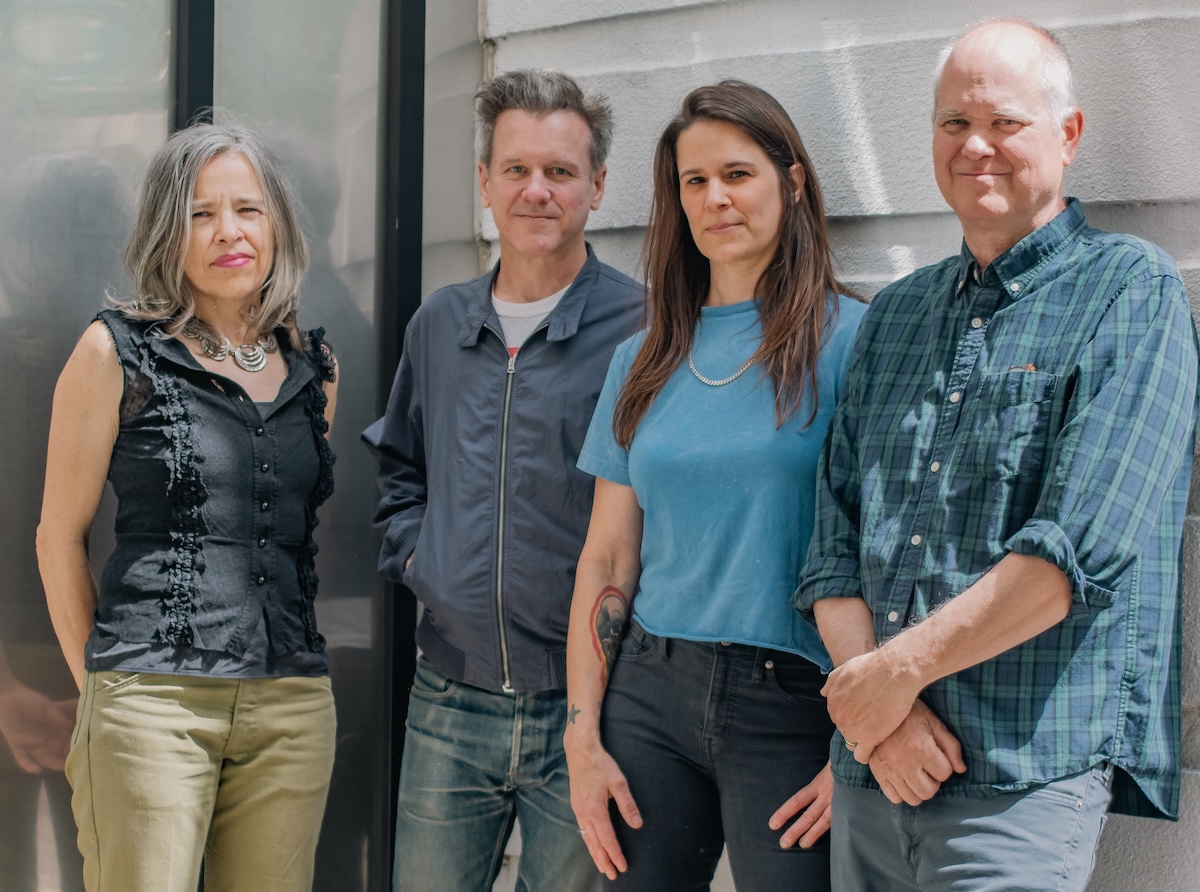

That sense of barely contained energy permeates Songs in the Key of Yikes, which serves as both a sonic departure from its predecessor and a pointed response to our current moment. Where 2022’s Wild Loneliness was largely recorded in McCaughan’s basement studio during lockdown—“one member at a time because of the pandemic,” he says—the new album represents a return to their full-throttle approach. The shift was partly inspired by new addition Laura King, “a hard-hitting punk-rock drummer” whose presence gave the band fresh musical direction.

“I think the record is a little bit of a reaction to having to make Wild Loneliness under lockdown conditions,” McCaughan explains. The previous album had “a cool character that’s its own,” but was quieter, and as a result more acoustic-focused. Recording at Sonark Media outside Chapel Hill allowed for a different approach. “The idea of being able to make a real rock record again was very appealing.”

Lyrically, Songs in the Key of Yikes functions as what McCaughan calls “a check-in” on our collective mental health. “How’s everyone doing?” he asks rhetorically. “What are we all doing to not lose our minds in this era? First of all, there’s still a pandemic. Second of all, fascism is on the rise. It’s a real test for everyone’s mental health.” The album’s song titles—“No Hope,” “Bruised Lung,” “Care Less,” “Everybody Dies”—might sound pessimistic, but McCaughan sees them as part of a necessary balancing act. “What things do you let go of in order to not just be obsessing about them? And what things do you invest more time in trying to repair or address?” Amid all this heaviness, the album’s first single, “Is It Making You Feel Something,” steps back to offer meta-commentary on the creative act itself, suggesting that in dark times, perhaps emotional connection is sufficient. “Don’t overthink things,” McCaughan explains. “Don’t ask a song to do too much. If it is making you feel something, then maybe that’s enough.”

This pragmatic approach to both coping and creative output reflects how Superchunk has evolved over the years. In the ’90s, McCaughan recalls, “the band was really our day job. We still work at it when we’re doing it, it’s still a job to some extent, but it’s not our only job. So there’s less pressure.” That reduced pressure has been freeing: “We’re just doing stuff that we think is gonna be fun for us and fun for people coming to the shows.”

McCaughan splits his time between Superchunk and running Merge Records, the label he and bassist Laura Ballance co-founded in 1989 that’s become one of indie rock’s most respected imprints, releasing landmark albums by everyone from Neutral Milk Hotel and Magnetic Fields to Arcade Fire and Spoon. “When we’re not on tour or in the studio, that’s pretty much what I’m doing,” he says of his label work. A recent partnership with Secretly Group has expanded their operation, allowing McCaughan to maintain the artist-run identity that’s been central to Merge’s mission while still being able to take the Superchunk show on the road.

“Having great people that I’m working with allows me to go on tour for a couple weeks,” he explains. “I think that’s also important to the identity of the label, because bands that we’re working with and other bands know that it’s an artist-run label.” In an era where label identity has largely dissolved, Merge has maintained a recognizable aesthetic and ethos. “We don’t just put out guitar-based indie rock records anymore,” McCaughan notes, “but hopefully everything that we do still makes sense that it’s on Merge.”

That artist-run philosophy extends to how Superchunk approaches live performances, navigating the expectations that come with being a legacy act while still prioritizing new material. “When we play shows, there’s young people and then there’s people that have been coming to see us since the early ’90s,” McCaughan observes. “People want to hear the songs that they love and are familiar with, but you want people to want to hear the new songs also.”

The band embraces both sides of their timeline—they’ll celebrate milestones like the 30th anniversary of Foolish, which they marked last year with a run of live shows that focused heavily on the record, but they also load their setlists with recent material. “I remember when we were touring for [2018’s] What a Time to Be Alive, we played a lot of that record in those sets, and the audience was great with that,” McCaughan says. He’s also genuinely inspired by other long-running acts who’ve maintained their vitality. “I went to see Bow Wow Wow last year,” he continues. “I love seeing bands that I grew up with and maybe didn’t get to see at the time. Last time I saw Psychedelic Furs, I think it had been maybe a 35-year gap, and they were amazing.”

This consideration reflects Superchunk’s current outlook. At 36 years in, they’re not under pressure to play shows, or even make records. “When we do, it can be on our own terms and be what we want it to be,” McCaughan explains. “By the same token, because we’ve been doing it for so long, if we’re gonna go through the trouble, it should be good. It should be worth it.”