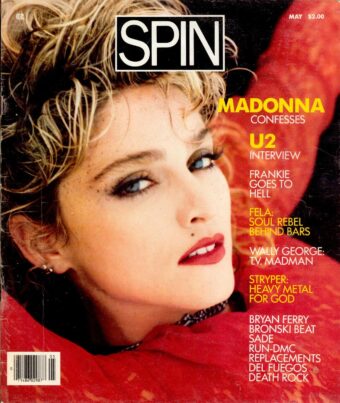

Madonna graced the first cover of SPIN forty years ago, which coincides with the anniversary of her film debut, Desperately Seeking Susan. She also happens to be the actress with the most Golden Raspberry Awards, taking home nine during her tenure, besmirching almost half of her eighteen films.

And yet, there has never been, and never will be again, an American pop culture figurehead as pervasive as Madonna. An intergenerational cultural phenomenon who sprang into the early ’80s zeitgeist with her first album, Madonna, in 1983, she became her own symbol of reinvention, a trailblazer of free speech, integral in a softening towards the depiction of sexuality in the 1990s, and a pseudo patron saint for the LGBTQ+ community. She was larger than life, demonized for her romances and lionized by Gen X.

More from Spin:

- Sean ‘Diddy’ Combs Found Not Guilty On Three Most Serious Charges

- ‘Today’ Is The Day For A New Foo Fighters Song

- Unknown Mortal Orchestra’s Ruban Nielson Channels Sister’s Death Into His Darkest Music Yet

She has managed to stay incredibly relevant, despite being an artist who, once so ahead of the times, now seems defined by them. But despite her legacy as a musical gamechanger, cinematically she remains critically demeaned.

Arguably, a reputation as a sexual iconoclast made her easy to dismiss. Camille Paglia, who likened her star persona to something “worthy of Cecil B. Demille” remarked in the 1990s: “her extracurricular escapades… made it difficult but not impossible for cultivated and discriminating people outside the pop realm to see that she is an artist.”

Madonna has never been the best (fill in the blank) compared to her contemporaries. But she leaned into her own persona, her resiliency now plowing into uncharted territory as an aging female pop singer who, for better or worse, refuses to behave in whatever rigidly prescribed role expected of her.

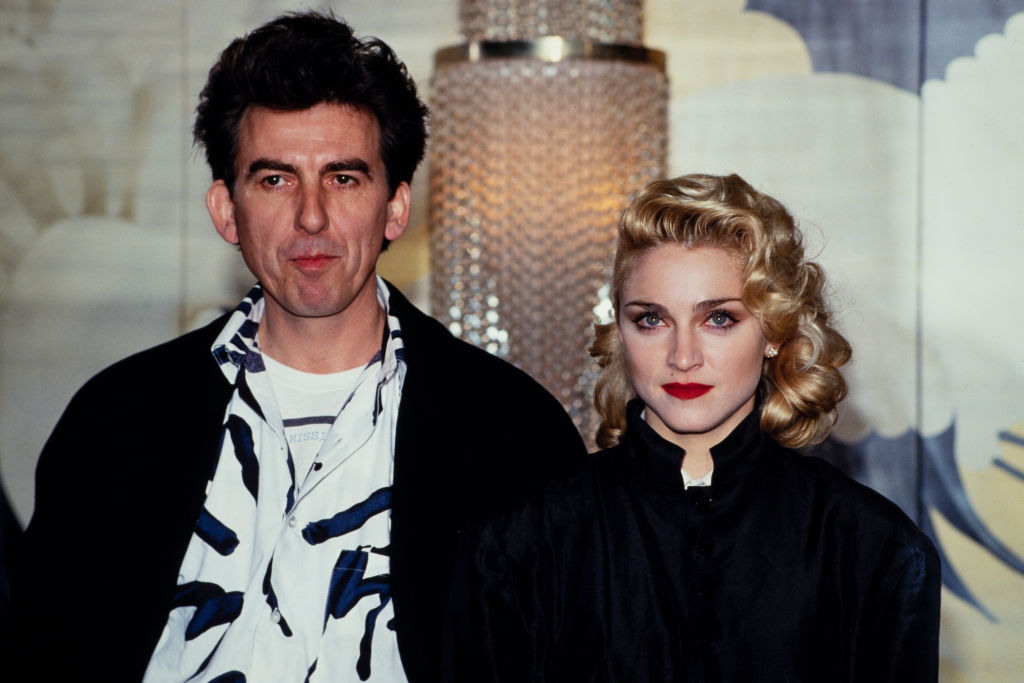

In Susan Seidelman’s 1985 sleeper hit Desperately Seeking Susan Madonna plays a version of herself as a rascally bohemian pursued by bored housewife Rosanna Arquette. The same year she also played a similar but inconsequential figure in Vision Quest, performing her track “Crazy for You.” But then everything took a considerably dark turn, beginning with 1986’s Shanghai Surprise, which “won” her the first of those Razzies.

In retrospect, it appears many of these films were unfairly maligned by Hollywood, which perhaps sought to punish her brazenness and outspokenness. But Madonna’s failure to prove herself as an actor reflects a bizarre complexity of intersecting elements, where nearly all her comparable colleagues distanced themselves from her outré attitudes towards sexuality. Sparring with Cher, Mariah Carey and even Elton John cemented a reputation of an impossible pop diva never really able to articulate herself well enough to justify her haughty pretentiousness.

Madonna was married to Sean Penn during the filming of Shanghai Surprise, a performance justifiably harpooned, even if she was hardly alone. Cast against type as a pseudo virginal missionary who tells white lies to locate a bounty of missing opium for wounded soldiers, an inability to navigate even the simplest exchanges of dialogue derails her performance. Her relationship with the equally pretentious Penn (whom she refers to in the infamous 1991 documentary Madonna: Truth or Dare as the “love of her life”) also revealed her championing of arthouse cinema, both of them crusading for the cause of Dominique Deruddere’s 1987 Crazy Love.

She snagged a Razzie for the woeful Who’s That Girl? (1987), a goofy attempt at screwball comedy with Madonna as a whiny, peroxide blonde sporting a ruinous Philly accent. Another Razzie followed for the documentary about her “Blonde Ambition” tour in Truth or Dare in 1991.

The 1990s proved to be her most chaotic but creatively fruitful screen period, beginning with Warren Beatty’s Dick Tracy, perhaps her best performance working alongside someone with whom she was romantically involved. Woody Allen gave her a cameo in the forgettable Shadows and Fog (1991) while her best role to date, 1992’s A League of Their Own, was an affirmation of how Madonna could be directed effectively by channeling her abrasive persona.

But a savagely ridiculed performance in 1993’s erotic thriller Body of Evidence assisted in souring the reception of Abel Ferrara’s far superior Dangerous Game the same year, also starring her, but a film she spoke out against souring Ferrara against her indefinitely. Yet her performance generated some of the most positive reviews of her acting career.

Cameos followed, including Blue in the Face (1993), another Razzie as a lesbian, leather-clad witch in Four Rooms (1995), and a highly underrated turn as a phone-sex brothel madam in Spike Lee’s excellent Girl 6 (1996).

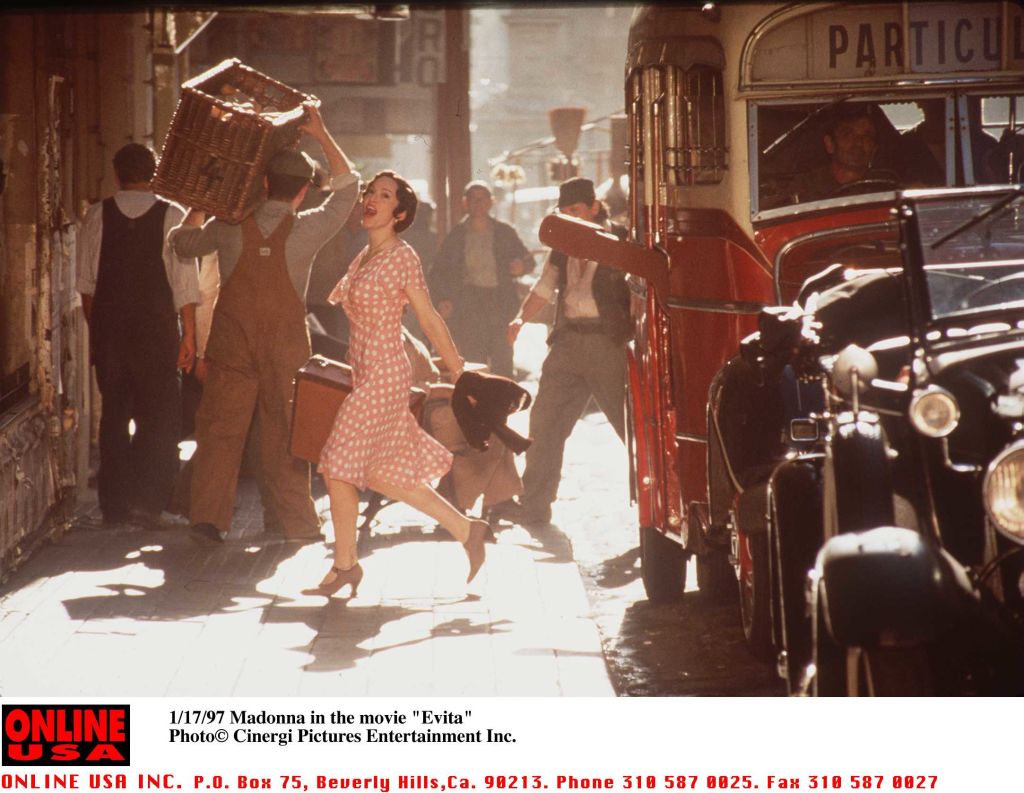

And then came Evita (1996), the hyperbolically praised adaptation of the Broadway musical, which garnered Madonna a Golden Globe Award. In hindsight, Evita is a superficial and visually ponderous musical, but what remains most interesting is its mimicry of how the culture was conditioned to consume Madonna — as a pop star lip synching in what feels like an extended music video.

The start of the new millennium seemingly shuttered Madonna’s tenure as an actor. She got another Razzie for The Next Best Thing in 2000. Her relationship with British director Guy Ritchie resulted in the notorious Swept Away remake — she was awarded a Razzie for Worst Actress and Couple, which just seems bitchy, and then scooped up another Worst Supporting Actress Razzie for a cameo appearance in the James Bond film Die Another Day, which just seems unfair.

Her toxic romance with the cinema continued. She directed a bizarre but serviceable feature about three hapless London roommates in Filth and Wisdom, which credited more global influential auteurs than any project directed by a sycophantic film student. She followed this, as writer, producer, director and actor, with the more palatable but limited W.E. (2011), imagining the imperiled romance of Wallis Simpson and King Edward VIII through the eyes of a wealthy, unhappily married woman during a 1998 auction of the couple’s estate.

Rumblings about a self-directed biopic suggest she’ll return to the director’s chair, though a traditional film or series would seem unable to adequately encapsulate her life. But maybe Madonna is the only human who can correctly articulate her own story, seeing as how her cinematic imagery, as projected through the lens of others, has historically felt either inauthentic or uncomfortably pompous.

The closest we ever came to an authentic version of Madonna’s persona was Truth or Dare. Whatever a final cinematic moment might look like from Madonna, to reference one of her best B-sides, “Sky Fits Heaven,” she’s always traveled down her own road. And she sees signs the rest of us aren’t privy to.

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.