The Reconstruction period immediately following the American Civil War was a time of change in the South; when the former Confederate states worked on reintegrating into the Union, Black slaves adjusted to life as newly-freed slaves, and new constitutional amendments were put in place to guarantee citizenship and voting rights for men, regardless of race.

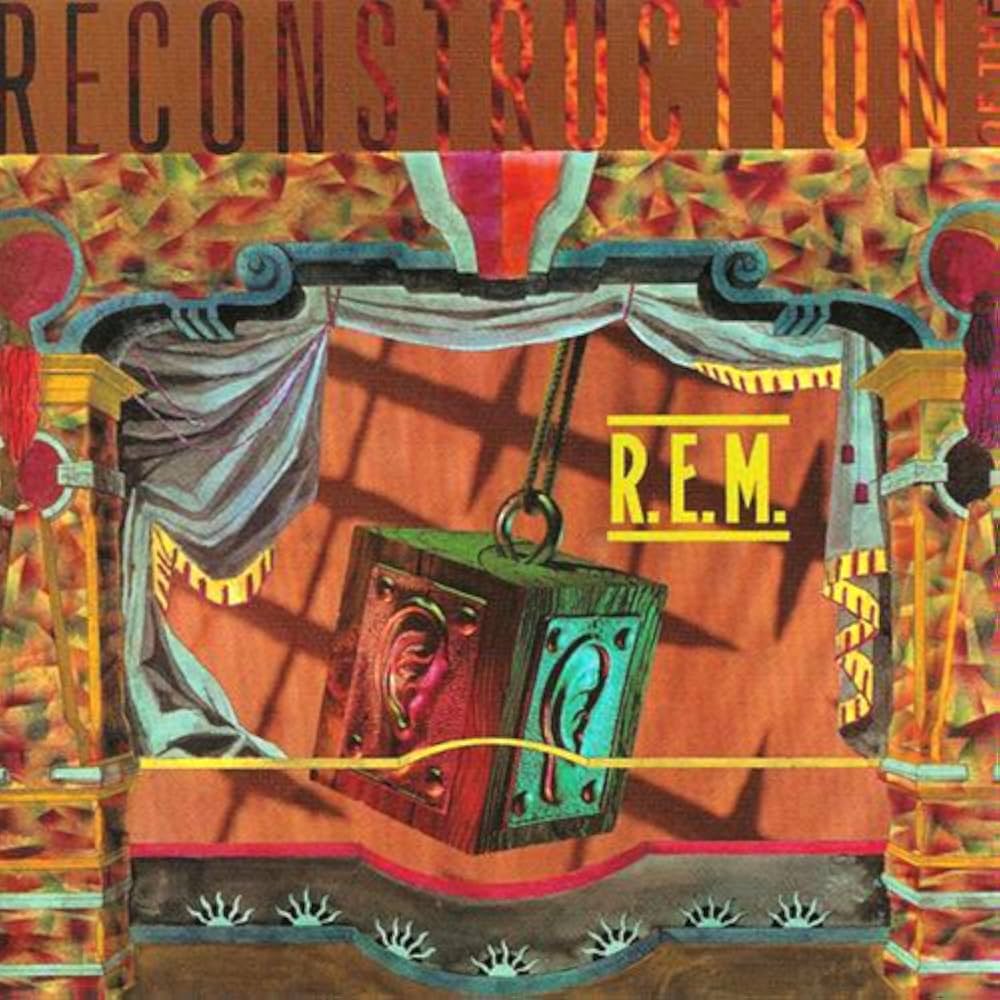

While there are no specific references to this transformative time in American history on R.E.M.’s third album, Fables of the Reconstruction, the 11 songs in this collection reflect a time of change for the band itself.

More from Spin:

- Röyksopp’s Freedom Frequency

- ‘Everybody’ Dance: David Byrne Details New Album, Tour

- New Book Explores How ‘Jagged Little Pill’ Changed Everything

Released 40 years ago on June 10, 1985, it’s a significant time-stamp within the band’s 14-album catalog; a record about the American South, and what it means to be Southern at that time, at least from the collective perspective of Michael Stipe, Bill Berry, Peter Buck, and Mike Mills.

For their first two albums—Murmur (1983) and Reckoning (1984)—the band from Athens, Georgia worked with Mitch Easter and Don Dixon at Reflection Studios in Charlotte, North Carolina. But this time round, they decided to hire producer Joe Boyd—known for his work with Nick Drake and Richard and Linda Thompson—to record the album in London, where it rained and snowed almost the entire time during the studio sessions, which might help explain the record’s darker tone. Tensions reportedly ran high as the band adjusted to Boyd’s more strict work ethic rather than the quick, collaborative, and experimental strategy of Easter and Dixon. It was not only a different recording experience for the group, but for the first time in their career, they were making a record outside of the South; a reported cause for the band’s homesickness.

It was a reconstruction, if you will, of how R.E.M. operated.

But the move paid off. When Fables of the Reconstruction was released on June 10, 1985, it brought R.E.M. another step closer to mainstream popularity, reaching No. 28 on the Billboard 200, winning the CMJ New Music Award for Album of the Year in 1985, and selling 500,000 copies, with a Gold certification to boot in 1991.

While the record wasn’t a complete departure from the band’s previous albums, boundaries were being pushed sound-wise, little by little, from Buck’s eerie harmonic guitar intertwined with violins and cellos in “Feeling Gravity’s Pull” to the use of banjo in “Wendell Gee,” a subtle departure from the glittery, jangly guitarwork that was Buck’s signature sound on the band’s earlier works.

Fables of the Reconstruction is perhaps R.E.M’s most southern record, not necessarily in sound, but in themes and imagery, depicting a South that both clings to its sordid past and yearns to move forward into the future.

Take “Driver 8,” a song I wrote about for SPIN’s “The Best and Worst Songs From 1985” list. Sure, it’s about trains. But it could also be interpreted as the feeling of uncertainty about the future, of where our ultimate destination lies. Then there’s the elusive old man living on the outskirts of Southern society in “Old Man Kinsey,” which was co-written by Athens artist Jeremy Ayers, who was pushing the boundaries of Southern life by introducing Athens to the fashion and glamour of Andy Warhol and the New York City arts and music scene. “Maps and Legends” is an homage to Georgia artist and Baptist minister Howard Finster, who designed the art for the band’s second album, Reckoning.

Forty years later, R.E.M. is arguably remembered more within the mainstream consciousness for Out of Time, Automatic for the People, and Monster, the three albums that made them one of the biggest bands of the 1990s. But it was Fables of the Reconstruction that put them on that path.

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.