I was 21 when Brokeback Mountain was released. I have such fond memories of going to the gay bar in my hometown of Minneapolis and dancing to bass-driven remixes of Gustavo Santaolalla’s gentle, emotive original score. Even in its house-music version, there’s an inherent sadness in these songs, and sometimes that’s the best to dance to.

Upon its release, Brokeback Mountain felt very validating, but also very melancholic because it felt like we’d come so far and yet still had so far to go.

What’s difficult about reflecting on the cultural remnants of 2005 is the realization of how such uncertain times suddenly seem less dire, even formidably stable, in comparison to the regressive political maelstrom which has engulfed American sensibility 20 years later.

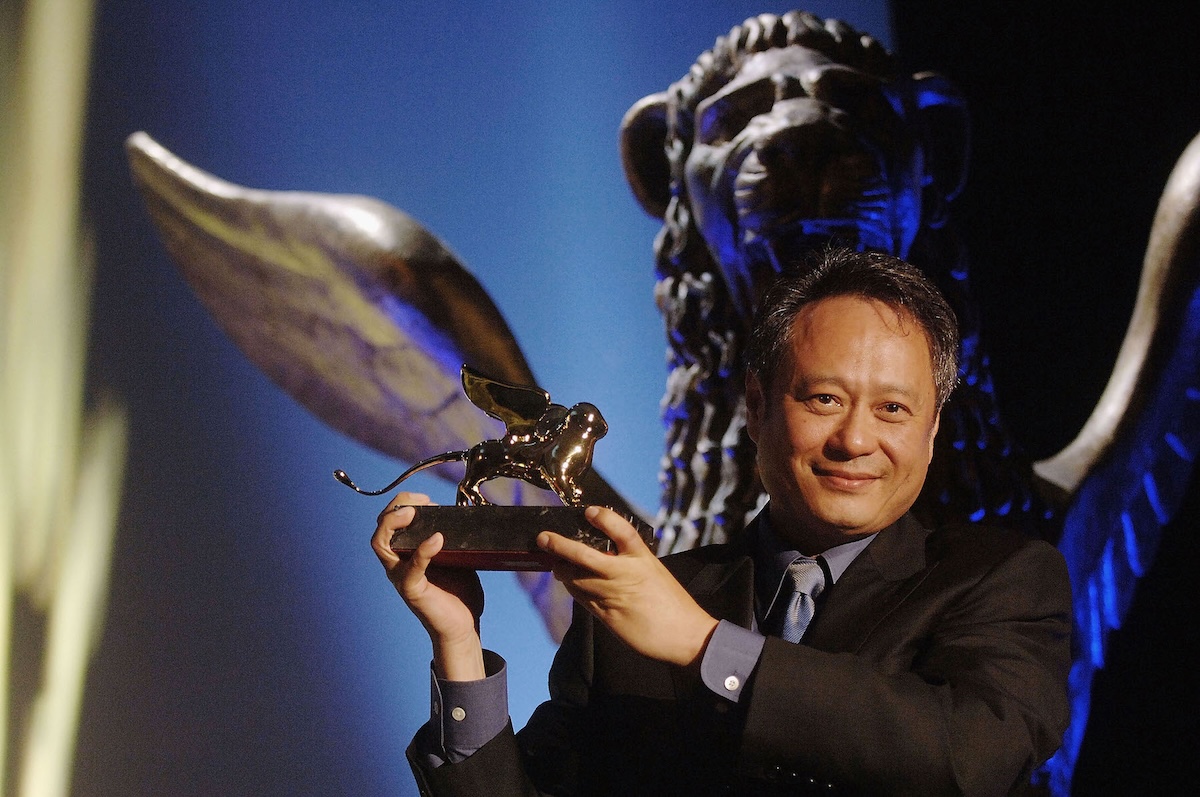

And yet, in the middle of the second presidential term of George W. Bush Jr., while the Iraq War raged and Hurricane Katrina tore through the soul of America’s South, a project nearly a decade long in the making landed like a meteor, forever altering queer visibility in the cinematic landscape. On September 2, 2005 Ang Lee’s Brokeback Mountain premiered at the Venice Film Festival, nabbing the prestigious top honor of the Golden Lion, and launching an awards campaign which would bear significant fruit.

Queer representation suddenly felt as if it had reached a pinnacle long out of reach thanks to a film headlined by rising A-list stars Heath Ledger and Jake Gyllenhaal. They portrayed a pair of lovestruck cowboys in 1960s Wyoming, where rigid cultural dictates and virulent homophobia demanded they remain closeted for their survival, inevitably suffocating a romance doomed from its onset.

Despite anticipated critiques of a narrative defined by queer tragedy and miserabilism, conversations—thus, our consciousness—about queer inclusivity suddenly began to shift. Retrospective conversations conform to a template which decries the casting of heterosexual actors inhabiting gay roles, but our ability to eventually make such demands and distinctions was certainly assisted by the success of Brokeback Mountain and the participation of its matinee stars, which assisted in broadening the horizons (and legacy) of the film. In short, like most queer films of the period, it depended on appealing to the heteronormative, which means walking a fine line between titillation and empathy.

Brokeback was not alone in a burgeoning landscape of celebrated queer films from 2005, with Felicity Huffman in TransAmerica and Cillian Murphy in Neil Jordan’s Breakfast on Pluto bowing to certain acclaim, while Philip Seymour Hoffman took home a Best Actor Academy Award for portraying the effete iconoclast Truman Capote.

But certainly no film sent tongues wagging more than Ang Lee’s overture, which was expected to win Best Picture at the Academy Awards, only to be locked out by the Academy’s unwillingness to bestow a queer film with top honors, instead awarding the Paul Haggis’ title Crash in one of the award show’s most notable upsets in its prolific history.

But the film didn’t go home empty handed. Of its eight nominations, screenwriters Larry McMurtry and Diana Ossana won Best Adapted Screenplay (based as it was on the 1997 short story by Annie Proulx), Best Director for Ang Lee, and Best Original Score for Argentinian musician Gustavo Santaolalla (who would win a second Academy Award a year later for Babel).

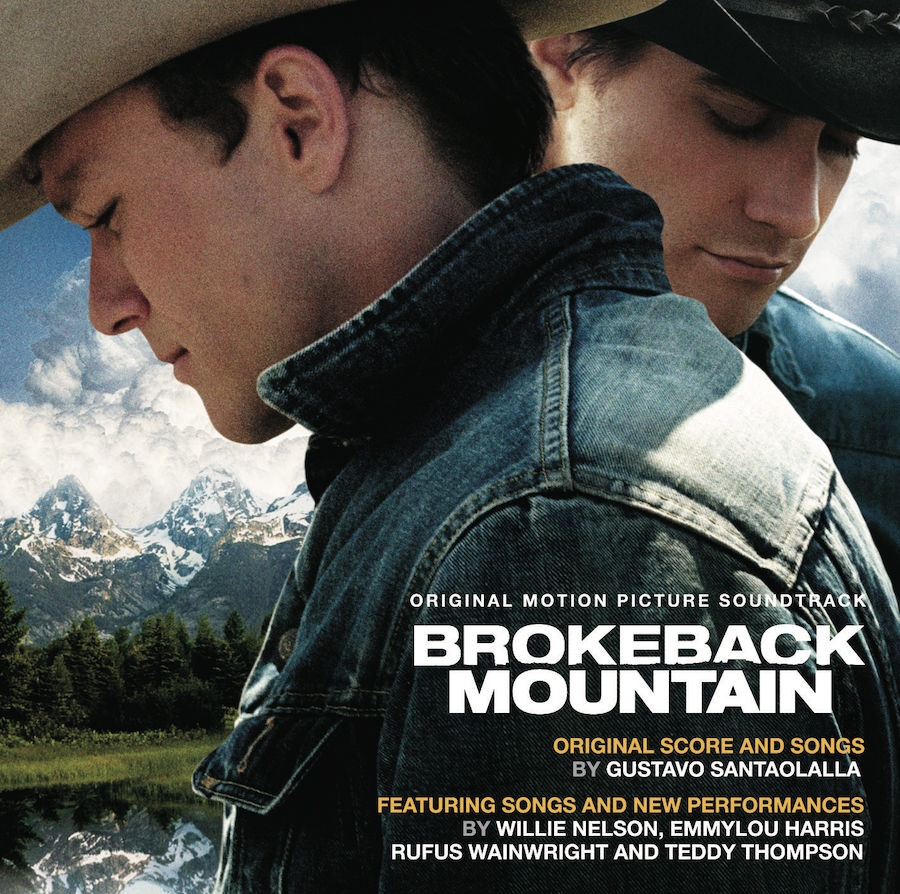

Following a theatrical re-release of the film for its 20th anniversary to celebrate Pride month, the soundtrack is slated to receive a vinyl release for the first time. Alongside Santaolalla’s original score, the release also included performances from Willie Nelson, Rufus Wainwright, Teddy Thompson, Emmylou Harris, Steve Earle, and Linda Ronstadt.

To commemorate the release, Gustavo Santaolalla shared his recollections of working with Ang Lee, how the score bolstered the film’s cultural impact, and, in his own words, how “as humankind we have evolved to some point, but suddenly it seems that we went back 50 years.”

How were you first approached with Brokeback Mountain?

It’s funny because I have a multifaceted career. I’ve done lots of different things. I started as an artist and producer making records when I was 17 years old and signed with RCA in Argentina. At the time there were no producers of the music that I was doing, alternative music. I don’t think even the word alternative music was coined then. Then I started really getting into production in the mid-’80s, and I had a wonderful phase in my career doing that and won a lot of Grammy Awards. I was always told that my music was very visual. As a matter of fact, I wanted to study cinema. I was always a big film buff since I was a kid. Unfortunately, when I finished high school, I was already making records.

The military rulers at the time led me to leave the country and they closed the Institute of Cinematography. There was no more school for cinema so I just devoted myself to my musical career, but I always have this attraction for cinema. Really the first movie that I did was Amores Perros. When I was doing Amores Perros I’d already released this album called Ronroco, named for this beautiful instrument, which actually I don’t use in Brokeback Mountain. I think it’s probably the only movie that I haven’t used that instrument.

That album led somebody to tell Alejandro G. Iñárritu, ‘You should have this guy do the music for Amores Perros.’ I met Alejandro, who asked me if I knew Walter Salles, which then led me to do Motorcycle Diaries. When we were presenting Motorcycle Diaries at Sundance they signed a distribution deal with Focus Features. Of course, Focus got me in touch with the script for Brokeback Mountain, which I loved when I read it. Then, I learned that it was based on that New Yorker story by Annie Proulx. At the time I was touring with Osvaldo Golijov, a classical contemporary composer, producing one of his works and playing some of my stuff with him too. We were rehearsing at Carnegie Hall. Finished the rehearsal, and I received a phone call asking me to meet Ang Lee in Manhattan at the Focus office.

I remember I took the subway, and I had my ronroco with me. I came in and we didn’t talk that much, but he pointed at the instrument so I started playing. He told me about his idea of using a guitar and it was incredible because I had the same idea when I read the script, the idea of something very spare. I knew my taste in composition, my use of silence and space.

I came back to Los Angeles and started writing, composing, and recording, because that’s my way of notation. I don’t know how to read or write music. I did my guitar pieces and the themes of the leitmotifs. I sent them what I composed three weeks after that. I got a phone call a week later from [film executive] James Schamus and he was laughing because when Ang Lee heard it, he said, “Damn, this music would be perfect for the movie.” And James told him, “No, this is the music for the movie.” I remember that phone call as it ended up with James telling me, “Well, I’ll see you at the Oscars.” Imagine. This was only my fourth movie, right?

One of the most remarkable things, I think, is the fact that I gave him a ton of music. He used all of it. And all this music was prior to one frame being shot. Nothing was filmed. I did the music on the basis of the script and my connection to the story and the characters. It was obviously Ang’s genius to say, “We’re going to put this here, we’re going to repeat.”

When I saw the first cut of the movie, it was spooky because you couldn’t believe that [the music] was done prior. Since then, obviously in 21 Grams also, 70% of the music I’ve composed [was] prior to seeing anything. Then obviously, you adapt. But the themes, the sonic fabric, it’s all there.

I remember when James praised my use of “negative space,” and I’ve never heard that phrase before. I just knew that I always loved to work with silence. I’m always talking about eloquent silences, not silences that are just empty, but silences that sometimes are louder than the loudest note. For Brokeback it was great because those characters didn’t talk that much as they were surrounded by silence, outside silence, and inner silence, too. It was an incredible experience. Also, I could make use of some of the things that also became trademarks. I have an affinity for “wrong notes.” That’s why I also love mistakes. We, human beings, make mistakes all the time. I love mistakes because some mistakes are really truly hidden intentions.

I have a nice story that connects with Brokeback. When I came to this country, in 1978, I was really bummed with the rock music situation here. I was coming from Argentina, where I was put in jail many times just for having long hair and playing electric guitar. Music still had that countercultural feeling. When I came here, bands like Boston, Kansas, were considered popular rock. But I preferred this new thing, which was punk. I belong to that generation and I embraced that as this movement had the energy I think this music should have.

So I’m just sending my music around town and don’t get an answer from anybody. Until one guy from a publishing company, an important publishing company, reached out. I met with a guy. We listened to the tape. I brought my guitar, I played some songs, and then we started talking. The guy said, “Listen, I got to tell you. You have a beautiful voice. You have great songs, great melodies. In every song, in every musical piece, at a certain point, you seem to hit the wrong chord. You seem to hit a wrong note in every single piece.” I told him, ”Probably this means that we’re not going to work together, but I have to tell you that I take this as a compliment.” I am looking for that point of inflection. I’m looking for that imbalance moment. Thirty years later I was reintroduced to him at a party for Neil Young. When this producer realized it was me, I reminded him “You told me that my music was good. My pieces were good, but at a certain point, I hit the wrong note. I hit the wrong chord. But when I met Anne Hathaway on Brokeback Mountain, she told me, “Man, in that intro when you hit that dissonant chord, that’s genius. Some people now like that wrong note.”

I also play the guitar and I leave the noises made by the instrument. Lots of people, when they play and record the guitar, they’re trying to avoid any noises when you run your hand on the fretboard. Sometimes I have even pushed those because it gives a human factor to it. That’s why I have gotten lots of comments that sometimes my music works as a character in the movies. Those elements and those trademarks are still present in the music of The Last of Us, or in the music of all the other works that I’ve done, too. Brokeback obviously was the first time that gave me the opportunity to show this thing to the world. It was incredible at that point in my life when that happened. I’ve already done so many other things, but the Oscars really, it’s another kind of beast. It’s a totally different thing. Imagine what it was like for me. Unbelievable. Since I was a kid, I always felt that I had something that could connect with people, with my music. But I never imagined something like that would happen to me.

Looking back, I don’t think you can recall Brokeback Mountain without the score. It’s synonymous with the characters. It’s interesting listening to you mention silence and dissonance. To quote you from a past interview, “We search for identity through music.” Your score is the audio identity of these characters.

That’s the best compliment that you can get. When somehow you feel that the music is an extension or another part of the character, it completes the character.

Even speaking about melody, it’s rare that it crystallizes in such a beautiful way. Reading about your life, it struck me that you have a lot of interesting parallels with gay men in the U.S., pertaining to your youth, fleeing the dictatorship in Argentina. I don’t know if this was true, but I read that the church suggested you undergo an exorcism as a youth. Is that true?

Yes, because I was raised Catholic, and I wanted to be a priest when I was very young. I was an altar boy. I had my first spiritual crisis when I was 11 years old. It wasn’t because a priest did anything to me. Unfortunately, one has to make that clear. In the Catholic church, they’ve covered awful abuses for years. No, it was truly a philosophical questioning about some of the principles of the church. I went every Sunday to church, I had communion, and as I said, I was an altar boy.

My thought, which I went and talked to the priest about was, I said, “If God is almighty and all kindness, how can eternal punishment exist? If you violated one of those 10 commandments, you will be in mortal sin, and then you’ll be eternally punished.” I could barely understand if you kill someone, but even stealing? I was thinking some people steal to give their kids food. Sometimes they steal from a huge supermarket. Still, as a kid, I had that idea that it wasn’t going to do any harm if somebody stole a loaf of bread. And yet, eternal punishment, this was the maxim. I asked the priest “How is it possible the devil exists? Could it be that the devil actually is on God’s payroll?” Imagine asking this of a priest as an 11-year-old kid.

They called my parents and my dad, who was an incredible man and lost when I was very young, accepted my beliefs. They kept going every Sunday to church, but the subject of my leaving the church was never brought up in my family again.

My spiritual search continues until today. I led a monastic life between 18 and 24. I lived like a monk. I had a group. A band. I lived in a commune, but it was a Yogi commune. We fasted every Monday. We didn’t do any drugs or drink any alcohol. We actually were celibate. I was at the peak of my rock success with my band and I led this life for almost seven years.

In many ways, it feels imperative to take some time to revisit this film from the perspective of today’s regressive climate.

At the time it was already ridiculous the movie didn’t win Best Picture. We won the Golden Globe with “A Love That Will Never Grow Old,” [a song from Brokeback Mountain] but the Academy didn’t allow it to be nominated because it didn’t meet a time requirement for the amount of seconds it had to be in the film.

I remember watching the Oscar ceremony and being crushed about the message that was being sent. As you said, the Oscars are another beast, and I don’t think at the time they felt they could give a gay film the top prize.

Correct. Also, it won Best Director and several other Academy Awards, but that was definitely their prejudice. Remember, this was a movie that they were trying to do for more than 10 years, and nobody wanted to do it. It’s so funny many of the main people involved in the movie were not from the United States. Ang Lee is Chinese, the director of photography, Rodrigo Prieto, Mexican. Composer, Argentinean.

I think that says something about how in the United States we’re not able to really look at ourselves. We need outsiders to reflect on our experiences. I feel this is apparent based on how this film even got made. As a final question, how long was it before you realized the significant cultural impact of this film? Because, as you said, you have a very private way of working. You sent Focus Features this score, this film got made, and then it landed. How long did it take before you realized how big this was?

To be honest, in a way, I always felt the weight of the project, the weight of the story. When I read the script, I remember thinking it really was an incredible love story about human beings in which the sexual part of it was anecdotic. It was a story about these people and how broken they were inside. Their story as human beings was transcendental.

I thought that this, with the combination that they were gay, was an explosive combination because of the weight of the story, because of the weight of the characters, because the human factor of it was so true. I always felt that something big was going to happen.

The controversy became senseless. The message about love and about desolation and longing went beyond any criticism. I’m really, really happy that they’re re-releasing the movie, that we’re going to have the possibility to see the movie again in cinemas. Remembering the film, especially in the days that we’re living.

They’re going to release the soundtrack on vinyl for the first time. There is a possibility that they will also release the score. Just the score on the vinyl. I’m very happy about all this.

Thank you for a really iconic film score. It meant a lot to me personally, and I think to a lot of others.

Thank you so much. It is what really makes my life worthwhile. When I see that something that I do can affect people in such a positive way, and that can touch people’s hearts, it gives sense to everything that I do.